There’s some disagreement about the best age to teach kids to read. Could your child benefit from early reading instruction? Find out in this article…

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Contents:

- Can a Very Young Child or a Baby Read?

- Should I Teach My Child to Read Before School?

- What Are the Benefits of Teaching a Pre-Schooler to Read?

- An Enriched Childhood Experience.

- Makes Things Easier For Them When They Start School.

- Makes Things Easier For the Parents Too.

- Avoids Leaving it to Chance That They Will Learn to Read Well in School.

- Improves Their Motivation to Read and Learn

- Might Improve Their Overall Academic Achievement

- A Rewarding Experience for the Parent

- When Should I Teach My Child to Read?

- Further Information

- References

Summary

- Some children as young as one or two years old can be taught to read, although a number of academics dispute this. It’s unclear what proportion of children are capable of reading early.

- Potential benefits of teaching very young children include:

- An enriched childhood experience – greater access to the world around them in their pre-school years, much of the information we encounter in life is presented in print.

- An easier start at school – children have to deal with a completely new social environment when they start school and on top of this there is an academic expectation that they will learn to read in a fairly short time. Youngsters who’ve had early reading instruction at home have one less thing to worry about.

- Less stress for the parents – schools expect a lot of support from parents to help them get children reading quickly. It’s common for children to be set homework to complete with parents right from the start. This is much easier to do if the children have had early reading instruction at home.

- Avoids leaving it to chance that they will learn to read well in school – if children don’t get off to a good start at school, the odds that they will catch up aren’t very good. Many children still leave school with poor reading skills.

- Improves their motivation to read and learn – early readers grow in confidence because they notice they are ahead of their classmates. Children are more eager to do things they are good at.

- Might improve their overall academic achievement – children with good early literacy skills tend to do better at school. There is some evidence that very early readers stay ahead of their classmates and that early reading can improve general knowledge and even IQ.

- A rewarding experience for the parent – many parents feel a great sense of achievement when their children learn to read and they take great pride in being their child’s first teacher.

Can a Very Young Child or a Baby Read?

No one knows for sure what proportion of young children are capable of early reading because the research hasn’t been done. However, we know for certain that some very young children can read if they are given the right kind of instruction.

We are sure of this because our own children were able to read hundreds of words before their second birthdays and they could read age-appropriate books independently before they were three. They could spell basic words accurately too.

We don’t think there’s anything unique about our children and we don’t think they were born with any special gifts; we just taught them how to read early using a synthetic phonics approach.

We’re not sure if this would work for all young children, but many other parents have successfully taught their kids to read. There are scores of videos online which show very young children reading, such as these from the ‘brillbaby’ website and these ones from another early reading programme.

Larry Sanger, a co-founder of Wikipedia, also taught his children to read when they were very young, as you can see from the videos below:

Mr Sanger has even written a lengthy essay on the topic, which you can access from the following link to his blog: ‘How and Why I Taught My Toddler To Read’.

In spite of abundant, easily accessible evidence that very young children can be taught to read, there are still critics who claim that it’s all a trick or the children have just memorised a few words or even a whole story. Sanger counters these objections comprehensively in his essay and we assess some of the arguments against early reading instruction in another article.

Should I Teach my Child to Read Before School?

No one can make this decision for you, it should be your own choice based on what you think is best for your child.

We’ve outlined some potential benefits below based on research and our own experience. You might also want to consider some of the arguments against early reading instruction which we discuss in a separate article.

What Are the Benefits of Teaching a Pre-Schooler to Read?

Different people have their own reasons for teaching their children to read early and they might also notice different benefits. However, potential benefits include:

- An enriched childhood experience.

- An easier start in school.

- Less pressure for parents.

- Avoids leaving it to chance that they will learn to read well in school.

- Improved motivation.

- Might improve overall academic achievement.

- A rewarding experience for the parent.

We look at each of these points in more detail below.

An Enriched Childhood Experience

We found that being able to read gave our children greater access to the world around them in their pre-school years…

Writing is everywhere in the modern world; so much of the information we encounter in life is presented in print. We take this for granted as adults, but for a child there is great excitement in discovering what road signs and shop signs are saying or even the labels on items in a supermarket.

Our kids would ask what some of the words and phrases meant (“congestion ahead”, “Half-price Sale!”, “low fat and sugar”) and so this also helped to increase their general knowledge and their vocabulary.

And being able to read allowed them to explore books more freely at a much earlier age. We continued reading to our children even after they could read fluently, but we found they also chose to read books independently when we couldn’t give them our time. This allowed them more freedom to pursue their own interests and they were able to read a much greater volume of books than they would have been able to if they had been relying on us to read to them every time.

Makes Things Easier For Them When They Start School…

Starting school can be a very stressful time for children. Even if they’ve had experience of pre-school, they suddenly find themselves in much bigger classes surrounded by unfamiliar faces and busy playgrounds full of older children. So they have to learn to cope with an entirely new social situation.

There are also more expectations of them at school in terms of their behaviour. They have to stay seated and keep quiet for longer periods and for the first time they are made aware of academic expectations…

Faced with such an overload of new things to deal with, it’s quite normal for children to feel a bit anxious, and those who struggle with reading sometimes feel ashamed, especially if they can’t figure out a word they’ve been asked to read in front of their classmates.

Experiencing negative emotions makes it harder for a child to think. This causes them to perform even worse, which can further increase anxiety and create a negative feedback loop (vicious circle).

Even children who aren’t struggling can feel under pressure to keep up with the rest of the class because many schools expect kids to go from a standing start to reading whole books in a relatively short time.

In the UK, government recommendations say that phonics should be taught first and fast.

It’s quite common for kids to get reading tasks for homework in their reception year because schools are under pressure to meet the government’s expectations of progress. Homework might involve learning the sounds of groups of letters or lists of sight words, in addition to reading specific books to a parent. Some kids find doing extra work at home difficult because adjusting to the new routines and social interactions at school exhausts them.

In contrast to most of their classmates, a child who has had early reading instruction won’t feel under pressure because they will find the initial work quite easy. Our own children breezed through their homework in a few minutes because it was all stuff they already knew inside out.

Of course, early readers still have to cope with the social dynamics of school life, but they have one less thing to worry about; a thing that happens to be the biggest academic challenge most children have to deal with in their first few years at school.

Makes Things Easier For the Parents Too...

Some of our friends and acquaintances told us they were having quite stressful experiences getting through all the homework tasks with their children when they started school. This was understandable…

Some schools use a lot of jargon in their homework instructions, and busy parents, who might be struggling to get an evening meal ready after work, can be pushed to find the time to get their heads around it all.

Some parents find themselves feeling torn between wanting to play with their children and wanting to help them with their schoolwork.

In contrast, we found teaching our children to read before they started school to be a completely stress-free experience (for us and our children). Doing it yourself means you can fit sessions in when you have the time and when your children are most receptive. You can teach them in a flexible, relaxed and unhurried way, working at a pace that suits you and your child.

Avoids Leaving it to Chance That They Will Learn to Read Well in School

Some people argue that they shouldn’t have to educate their kids at home because it’s the school’s job to teach their children to read. In an ideal world this would be true. However, the stark reality is that many children still leave school with poor reading skills.

For example, a report in the U.S. found that one quarter to one-third of children don’t even reach the most basic levels of literacy when they leave school, and around two thirds never become really proficient readers:1

In England, the Department for Education found that one in six 11-year-olds still struggled to read after seven years of primary education.2

The reasons why so many children struggle to read in English speaking countries are complex and varied and we look at the problem in more detail in our article ‘Why Do so Many Children Struggle With Reading?’. But, whatever the reasons, for many children, just attending school clearly isn’t enough to make them good readers.

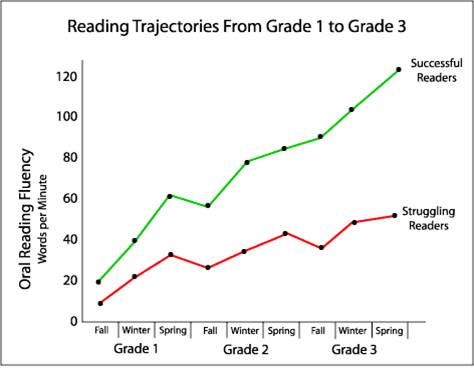

And if your child falls behind in the early years, the odds that they will catch up aren’t very good. Studies like the one below from the University of Oregon show that students who are struggling in the first grade tend to fall even further behind successful readers in later years.3

Giving a child some early reading instruction probably won’t guarantee they will become outstanding readers, but we think it’s likely to reduce the odds of them struggling at school. And this is something that could save the child and their parents a lot of stress and worry in the future.

Improves Their Motivation to Read and Learn

The late Michael Marland, a respected educationalist from the UK, once wrote:

“Being able to do is very close to wanting to do”.7

Marland had observed that children are much more likely to engage in an activity if they feel they have the ability to complete it successfully.

The observations of Marland are consistent with the expectancy-value theory of motivation, which is widely accepted in education. According to the expectancy-value theory, a learner’s motivation to do something is determined by how much they value the goal, and whether they expect to succeed at it.

So, even if a child views learning to read as a worthwhile goal, they will feel less motivated to practise reading if they think they aren’t going to be very good at it. In fact, some children who struggle with early reading can even feel emotionally threatened by it and they might start to engage in avoidance behaviours.

A child’s belief about his or her potential to succeed in a particular subject is sometimes called their academic ‘self-concept’, and children form their self-concepts by comparing their achievements with those of other children in their class. 8

Children who’ve had early reading instruction are likely to develop positive self-concepts about their reading ability because they will notice they are ahead of their classmates. And, according to the expectancy-value theory, this should have a beneficial impact on their motivation to read.

Might Improve Their Overall Academic Achievement

We’re not aware of any large controlled studies that have investigated the long-term effects of parents giving very young children reading instruction. However, there have been several studies which suggest that early reading instruction could have a positive effect on academic achievement:

- A study on the effect of parental involvement on children’s reading skills showed that teaching children about reading and writing words before school age had a positive impact on word reading in grade 1 and reading comprehension in grade 3.9

- A study published in the Journal of Educational Psychology found that “early reading achievement was the primary determinant of later reading performance”.10

- An extensive study involving 35,000 pre-schoolers in the United States, Canada and England, found that children who enter kindergarten with elementary mathematics and reading skills are the most likely to experience later academic success.11

- And a publication based on a report from the U.S. National Early Literacy Panel stated:

“The years from birth through age 5 are a critical time for children’s development and learning. … Children who develop more literacy skills in the preschool years perform better in the primary grades.” 12

Although the above studies show that early literacy skills are beneficial, they were looking at the effects of fairly basic literacy skills on children’s achievement. None of them investigated the academic outcomes of children who could read fluently before school.

However, in his essay on teaching toddlers to read, Larry Sanger discusses a study done in the 1960s which followed children who had learned to read at home before Kindergarten. The early readers in the study maintained their advantage over other children and those who had started reading earliest (around age 3) ended up with the highest average reading grade level six years later.

And a more recent study, which looked at children who had learned to read before school, found that they…

“…continued to make progress in reading accuracy, rate and comprehension, thereby maintaining their superior performance relative to a comparison group.”13

There’s also some evidence that early reading ability can have a positive effect on other areas of educational achievement.

For example, a study found that reading ability in the first grade was a strong predictor of reading comprehension, vocabulary, and general knowledge in the 11th-grade.14

Dr. Keith Stanovich, a leading cognitive scientist from The University of Toronto, has found that there are significant consequences associated with early differences in reading ability between children. He describes this as a “Matthew Effect” whereby an early advantage means “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer”.

The Matthew effect could be explained in part by the idea of academic self-concept, which we discussed earlier. Self-concept and achievement seem to influence each other: early achievement leads to a positive self-concept and the motivational boost leads to further improvements in achievement.

Importantly, the Matthew Effect results in differences that extend beyond basic literacy skills. A keen reader will also develop a wider vocabulary and a broader knowledge base that will enable them to engage in higher level thinking skills like reasoning and evaluation. Increases in comprehension and verbal intelligence allow for better understanding in a variety of subject areas.

And a recent study of identical twins supports the findings of Dr. Stanovich. Early differences in reading between the twins were linked to later differences in intelligence.15 Reading was associated not only with measures of verbal intelligence (such as vocabulary tests) but with measures of nonverbal intelligence as well (such as reasoning tests).

Personal testimonies from parents also suggest that children who get early reading instruction generally do better than average at school. Sanger mentions some examples of these in his essay and he has reported that his own children have continued to make good progress on his blog.

Of course, this sort of anecdotal evidence needs to be treated cautiously because people are more likely to report positive outcomes than negative ones. However, in the absence of large, carefully controlled studies, we think it’s worthy of some consideration.

Our own children certainly seem to have benefited academically: both of them gained full or near full-marks in all of their SATs (Statutory Assessment Tests) for literacy, and in more recent tests, their standardised literacy scores were in the top 1% nationally.

We’ve both had a university education, so it could be argued that our kids were likely to do better than average anyway. However, neither of us achieved the outstanding marks our kids have been getting at such an early age. Furthermore, they’ve been consistently outperforming other children in their year groups who have parents with similar academic credentials to us.

While most children are struggling to decode their first words, early readers can focus more on the content and meaning of their school work from a younger age. This could explain why they might make faster progress in other areas. While other children are learning to read, they are reading to learn.

A Rewarding Experience for the Parent

When we taught our children to read, it felt like a privilege to be intimately involved in such a crucial aspect of their learning. It was an immensely satisfying experience for us.

Other parents who’ve taught their children to read have told us they had similar feelings and we’ve read very positive comments on various online forums:

- Some people said it was one of the best things they’ve ever done for their children.

- Others said they felt great pride in being their child’s first teacher.

- Some parents felt a great sense of achievement.

These sentiments are hardly surprising because the parents realised that they had taught their children one of the most important skills they will ever need in life.

We haven’t heard anyone say they regretted teaching their children to read before school.

However, there are some parents and academics who argue that children shouldn’t be getting reading instruction until they are 7 years old. And some critics insist that it’s not even possible to teach a young child to read before the age of 4 or 5.

We assess some of the arguments against early reading instruction in a separate article.

When Should I Teach My Child to Read?

All children develop at different rates so there’s no precise age that’s ideal for everyone and it is up to each individual parent to decide.

You can help your child develop some early literacy skills such as phonological awareness from birth, but you couldn’t teach them to decode written words at this age.

The most important thing is that your child should have demonstrated they can understand spoken language before you think about teaching them to read.

This doesn’t mean they have to be speaking articulately, but they need to understand that words have specific meanings. Once they have shown signs that they have grasped this idea, either by pointing at things you mention, like a clock or a teddy, or doing actions when you mention words like ‘smile’, or ‘clap’, they are ready to learn about letters.

In the same way that children can learn what a cat or dog looks like from a picture, they can learn what a letter looks like. In fact, it is probably easier for a child to distinguish between most of the letters than it is to tell the difference between dogs and cats, which look very similar in so many ways.

Children can also learn the sounds associated with letters in the same way that they learn dogs say woof and cats miaow.

Further Information…

If you would like to know more about teaching your child to read, see our articles, How Can I Teach My Child To Read? and How To Teach Phonics.

You might also find our article about phonological/phonemic awareness activities for parents and teachers useful.

References:

- 2011 report from the U.S. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

- DfE Evidence paper: The Importance of Phonics: Securing Confident Reading

- University of Oregon, Big Ideas in Beginning Reading, Scope of Reading Difficulties in the US

- Source: Hempenstall, K., Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Education News (2001)

- See also the article: Waiting Rarely Works: Late Bloomers Usually Just Wilt, published in the American Educator 2004.

- Adapted from an article in The Learning Spy Blog: The Matthew Effect – why literacy is so important.

- Marland, M. (1993) The Craft of the Classroom, Heinemann.

- Muijs, D. and Reynolds, D. (2011) Effective Teaching: Evidence and Practice, Sage Publications Ltd.

- Sénéchal M, LeFevre JA. Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: a five-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2002 Mar-Apr; 73(2):445-60.

- Seven-year longitudinal study of the early prediction of reading achievement, Butler, Susan R et al.

- School Readiness and Later Achievement, Duncan, Greg J et al.

- Early Literacy: Leading the Way to Success, A Resource for Policymakers.

- Stainthorp R, Hughes D. What happens to precocious readers’ performance by the age of eleven? Journal of Research in Reading. 2004;27(4):357–372

- Cunningham, A. and Stanovich, K. Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental psychology, 1997

- Ritchie S, Bates T, Plomin R. Does Learning to Read Improve Intelligence? A Longitudinal Multivariate Analysis in Identical Twins From Age 7 to 16. Child Development. 2014. Summary.