Does knowing letter names help children learn to read more easily? Some people think so, but others disagree. Read our assessment of the arguments.

Introduction

While some educators claim that learning letter names is really important, others say this could actually make it harder for children to learn to read and spell.

To understand the reasons for these disagreements, we need to be aware of the role of letters in reading and spelling.

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Contents:

- Children Can Learn to Read Without Knowing Letter Names

- Why Do Some Pre-schools Teach Letter Names?

- Can Learning Letter Names Actually Hinder Beginning Readers?

- The Limitations of Working Memory

- Conclusion and Recommendations

- What Should I Do If My Child Has Already Learned the Letter Names?

- Further Information

- References

Summary

- Children need to know the sounds that letters represent in order to become proficient at reading and spelling. It isn’t necessary for them to know the names of the letters as well.

- Many schools teach beginning readers letter names just because they’ve always done it that way, not because it helps with reading. A number of popular and effective reading programmes don’t introduce letter names until after children have learned to read simple words.

- Teaching children letter names could potentially slow down their progress in the early stages of learning to read because the extra information increases the burden on their limited working memory.

- There is also evidence that knowledge of letter names can interfere with early spelling and it may also have a negative effect on early reading fluency.

- However, we don’t think you should be too worried if you’ve already taught your child the letter names. Most children can and do overcome any initial difficulties. Just tell your child that each letter has a sound as well as a name and tell them that they only need to say the sounds while they are learning to read and spell. If you keep reinforcing this idea (and avoid mentioning letter names) they will eventually access the letter sounds automatically without thinking about the letter names.

Children Can Learn to Read Without Knowing Letter Names

We don’t make much use of letter names when we read.

To illustrate this point, imagine trying to read a simple word like ‘cat’ to your child using the letter names, it would sound like ‘see’-‘ai’-‘tee’. Clearly, this doesn’t sound anything like cat.

And there’s nothing unusual about the word ‘cat’, we could have chosen dozens of simple words, such as ‘pig’, ‘bed’, ‘pan’ ‘clip, ‘trunk’ or ‘frog’.

Saying the names of the letters in these words doesn’t give us much of an auditory indication of what the words sound like.

In contrast, it’s relatively simple for a child to figure out many hundreds of simple words once they know the common sounds that are represented by each letter.

And children can read thousands of words once they’ve also learned the sounds represented by some common letter combinations, such as ‘ch’ in chimp and ‘ou’ in cloud.

Our writing system is based on an alphabetic code and children need to learn the relationships between letters and spoken sounds to understand this code.

This is the key idea that underpins phonics, the most effective method of reading instruction.

There is an abundance of evidence that children can learn to read very effectively without knowing the letter names.

A number of successful phonics programmes, including Jolly Phonics and Sounds-Write, which are popular in the UK, don’t teach letter names to beginning readers.

And in UK reception classes, thousands of children learn the basics of phonics without being taught letter names.

Both of our daughters were reading children’s books quite fluently (and spelling simple words accurately) before we even mentioned letter names to them.

Project Follow Through in the U.S. provided one of the clearest indications that it isn’t necessary for beginning readers to learn letter names. This was the most extensive educational experiment ever conducted with over 200,000 children in 178 communities included in the study.1

22 different models of instruction were compared and Professor Siegfried Engelmann’s method of direct phonics instruction (known as DISTAR) was by far the most effective programme for teaching reading. In his book, Teach Your Child to Read, Englemann stated:

“DISTAR does not initially teach letter names, because letter names play no direct role in reading words.” 2

Why Do Some Pre-schools Teach Letter Names?

If we accept that a knowledge of letter names isn’t necessary for reading, it might seem odd that some educators encourage children to learn them before they start reading instruction.

The reason why this is common practice is partly due to tradition. Many teachers continue to instruct in a particular way simply because it’s what they’ve always done.

Also, children do need to learn the letter names eventually; we use them to label things and to make lists for example, so perhaps teaching them early seems like the logical thing to do.

And some teachers might also be aware that those children who enter school knowing their letter names generally pick up reading faster than children who don’t.

In fact, research has shown that being able to name letters is one of the strongest predictors of future reading ability.

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s the knowledge of letter names that is helping these children with their reading.

Children who can name numbers before they start school also learn to read more quickly than other children, and numbers have nothing to do with reading.

One explanation for these correlations might be that the same parents who teach their children letter names and numbers are also reading to their children more regularly and engaging them in more meaningful conversations.

These children are likely to have a better vocabulary than most of their peers and a greater interest in books. Their parents are also more likely to value education and continue to help them with their reading when they start school.

In fact, some experiments where children were taught letter names (without extra parental input) have shown that learning letter names was no more beneficial for reading skills than memorising the names of geometric shapes or cartoon characters!3

According to Professor Diane McGuinness, a cognitive psychologist who’s done extensive research on teaching reading,

“there is a vast literature … that proves conclusively that knowledge of letter names per se has nothing to do with reading or spelling skill”

Professor McGuiness has also outlined the results of 3 large scale studies that looked at the impact of different teaching activities on children’s scores in standardised tests.

All 3 studies found that spending classroom time learning letter names did not improve the children’s reading ability 4. In contrast, learning the sounds represented by letters did have a positive impact.

However, there is evidence that a knowledge of letter names can help children to learn letter sounds.

This might be because children who can recognise letters by their names are already familiar with the individual letter shapes.

And some letter names contain the letter sound at the beginning or end of the name. For example, the name of the letter b (bee) starts with a ‘b’ sound and the name of the letter m (em) ends with an ‘m’ sound.

One study concluded that children can learn letter sounds quicker if they learn letter names at the same time5.

However, we’re a bit sceptical about the conclusion for several reasons:

Firstly, only a relatively small group of children were in each group in the study (20) and the difference in performance between the groups was also quite small. On average, the better performing group were only able to say the sounds of 2 extra letters compared to the other group.

To be fair, the researchers did do a thorough statistical analysis, but conclusions drawn from small samples with small differences in outcomes are always shaky.

Secondly, we have to question the quality of the instruction in the study. Children were taught by the researcher and a couple of graduate students rather than by qualified teachers, and the outcomes in all groups were dreadful by any standards.

Children in the best performing group only learned to say the sounds of 3.5 letters on average after 34 lessons spread over a 9 week period. This means it took an average of around 10 lessons to teach the children each letter sound!

To put this in perspective, 4 and 5-year-old children in English reception classes typically learn around 5 letter sounds per week.

Also, the rate of learning in the best group in the study wasn’t much better than for the control group even though the control children were being taught about numbers instead of letters.

Finally, the validity of the whole study is very questionable. The point of the research was to compare the benefits of learning letter sounds on their own with learning letter sounds and letter names at the same time.

But it’s clear that all of the students in the study were getting instruction about letter names outside of the study lessons. This is obvious because all of the groups could name more letters at the end of the study than at the start.

For example, at the end of the study, students in the control group were able to identify an average of 11 letters from their names which was more than twice the number they could identify at the start of the study. Remember, the control group were only supposed to be learning about numbers, not letters.

Researchers acknowledged that students in the group who were supposed to be learning letter sounds only might have been confused because they were being taught about letter names outside of the study lessons. This makes the results of the study void in our opinion.

It’s a bit like trying to investigate the benefits of a meat-free diet by giving people a small vegetarian snack in the afternoon while letting them eat what they want for the rest of the day.

If the subjects have bacon and eggs for breakfast and a burger for dinner you aren’t going to learn very much about the benefits of meat-free diets.

Another larger study that compared the different experiences of children in England and the UK made the following conclusion:

We did not find any evidence that learning the conventional names of letters first provides children with a boost that learning the sound labels first does not.6

Can Learning Letter Names Actually Hinder Beginning Readers?

If you’ve already taught your child the letter names, there’s certainly no need to feel guilty or unduly worried about it.

Millions of children who learned their letter names before school have gone on to become fluent readers.

However, there is some evidence that early knowledge of letter names can impair children’s spelling and there’s reason to believe it could slow children down when they are learning to read.

Remedial reading tutors such as Alison Clarke of ‘Spelfabet’ have noticed children incorrectly spelling words such as ‘car’ as ‘cR’ and ‘bell’ as ‘bL’. This is a sign that they are confusing letter names with sounds.

Several studies have also shown that early knowledge of letter names could interfere with children’s ability to spell accurately.6,7,8, 9

This can sometimes lead to bizarre errors such as “yrk” for work. Presumably, this error arises because the first sound in the letter name for y is a /w/ sound.

Research has shown that young children confuse letter names with sounds, syllables or whole words when they spell.

For example: ‘came’ might be spelled as ‘kam’, ‘you’ as ‘u’ and ‘are’ as ‘r’. Of course the latter 2 examples are commonly used in texts these days, but we still need correct spellings in more formal written communication.

A study comparing English and US children showed that these problems are a direct consequence of learning letter names.6

English children don’t learn letter names when they start school whereas American children do, and the errors described above were far more common in USA children.

English children do make some of the same errors, but only once they start to learn letter names in their second year of schooling!

Researchers in the same study also found some errors associated with learning letter sounds, but these only occurred in made up words ending in a ‘short u’ or ‘uh’ sound. This is unlikely to cause a problem because real English words don’t usually end in a short u sound.

Some academics also think learning letter names can interfere with reading…

Dr. Jonathan Solity, a lecturer in Educational Psychology at the University of Warwick, England, has conducted extensive research on early reading and concluded:

“Teaching letter names and sounds together increases the memory load quite significantly… potentially confuses children and doubles the amount of information they are required to learn.” 10

Professor Diane McGuinnes has also argued against teaching the letter names in the early phases of instruction on the grounds that letter names can confuse students.

Some remedial reading tutors have also noticed children confusing letter names with sounds and there’s an example of a student doing this in this video about 7 minutes in. The teacher goes on to discuss that the girl has a problem with this.

The idea that knowledge of letter names could confuse children might seem strange; almost everyone who can read fluently knows their letter names, and they don’t get confused by them. But things are different for beginning readers.

Skilled readers can recognise words automatically, but for beginning readers, word recognition takes a lot of mental effort, and the concerns Dr Solity raised about memory load are quite important…

The Limitations of Working Memory

We use our working memory whenever we have to hold information in our short-term memory while we perform some kind of mental task, such as multiplying 23 by 15 in our heads. And we rely heavily on our working memory when we are learning to read.

Working memory involves more than just using our short-term memory. It might also involve processing information from the environment, which we receive via our senses. And at the same time we might also have to retrieve knowledge stored in our long-term memory so we can make sense of everything.

When we read, we have to process the incoming visual information for each letter and decide what sound the letter shape represents. We then have to combine all the sounds together in our working memory to construct the word and retrieve information from our long term memory to see if we recognise the word and understand what it means.

Next, we need to keep each word in mind while we process the letters in the next word and then string all the words together in a sentence. Finally we have to figure out the overall meaning of the sentence.

As we mentioned earlier, experienced readers perform most of the above steps automatically, although they might have to pause and think when they come across an unfamiliar word. However, for beginning readers, there is a much greater burden on the working memory.

This can cause problems for beginning readers because (according to cognitive load theory) our working memories have a very limited capacity, and thinking becomes increasingly difficult if our working memories get overloaded.11 Any extra information that we have to think about uses up space in our working memory and makes tasks more difficult.12

When a child has been taught letter names alongside the sounds, they will have two auditory representations stored for each letter in their long-term memory (the sound of the letter name and the spoken sound the letter represents).

The child will retrieve both sounds when they look at the letters in a word and they will then have to make a decision about which sound is most appropriate for reading the word. This means their brain has to do extra processing.

They then need to hold their decision in mind while making another decision for the next letter and the next. This decision making will use up extra space in their working memories and they will process the information more slowly.

Processing speed is critical for fluent reading. Good readers process written words at speeds that are similar to the rate we process spoken language – in less than a tenth of a second.13

Anything that slows down the processing of words can reduce reading fluency and reading comprehension.

The limitations of working memory are especially significant for young children because they typically have much smaller capacities than adults, so their working memories can be more easily be overloaded.14

A good analogy is to consider what would happen if we taught 2 different ideas when children are learning what digits represent.

Suppose we told children that the digit 1 represents one item, but it also has a name, “egy”, and 2 represents two items and has the name “ketto” and so on. These are actually the Hungarian words for the numbers and I’ve listed all the the Hungarian words for 1 to 10 below:

1 | one | egy |

2 | two | kettő |

3 | three | három |

4 | four | négy |

5 | five | öt |

6 | six | hat |

7 | seven | hét |

8 | eight | nyolc |

9 | nine | kilenc |

10 | ten | tíz |

Would teaching these extra names for the digits make it be easier or harder for a child to learn what they represent?

And when they start learning about bigger numbers, and are expected to read, for example, the number 234 as two hundred and thirty four, would knowing the extra names be helpful?

We think the answer to both the above questions is no.

Knowing the extra names would be more likely to interfere with the key information and confuse children. And we’ve just used the numbers one to ten in this analogy; children have to learn 26 letter names!

Conclusion and Recommendations

Having looked at the research, it seems clear that teaching letter names to your child is better than doing nothing.

Matching names to the letters of the alphabet can help to familiarise your child with the shapes of the letters and this could give them a head start when they start reading instruction.

Also, knowing the names of some of the letters can help your child to learn the letter sounds later because some of the names begin or end with the letter sound.

However, teaching your child letter names early could potentially have a negative impact on some aspects of their literacy in the future, particularly their spelling.

This is unlikely to cause any serious or permanent problems for your child, but it could cause them some confusion and slow down their progress in the early stages of reading instruction.

Teaching your child the common sounds of each letter instead of their names would be a more productive use of your time.

Knowing the letter sounds will be far more beneficial for them when they start phonics instruction and there are no unwanted side effects.

We aren’t suggesting that children should never learn their letter names; obviously they are important for spelling out loud like a grown up and lots of things are labelled or ordered alphabetically.

But it’s best to leave letter name recognition until after children are reading quite fluently.

We agree with Dr. Jonathan Solity’s comments on this issue:

“Focussing on letter sounds initially, when teaching reading and spelling, minimises what children have to remember and keeps teaching simple.” 15

However, the reality is that many children will encounter letter names via TV programmes or in pre-school. This is especially true in the USA.

If you are a parent who lives in an area where letter names are taught, it probably makes sense for you to at least mention these to your children.

However, it’s still better to teach letter sounds first and to spend more time working on these to lay the foundations for future phonics instruction.

What Should I Do If My Child Has Already Learned the Letter Names?

As we said earlier, don’t worry too much about it. For some children, this might not even result in a noticeable problem, and for others, it should only be a temporary hindrance, not an insurmountable problem.

Just tell your child that each letter has a sound* as well as a name and tell them that they only need to say the sounds while they are learning to read and spell.

*Technically, letters don’t have sounds; they represent sounds, but you don’t need to concern your child with this subtle difference.

A good analogy to use with your child is to compare letters to animals. Show them pictures (or models) of animals and ask them the names of the animals and the sounds they make: a dog makes a ‘woof’ sound, a cat makes a ‘meow’ sound and a cow makes a ‘moo’ sound etc. Then say: “just as each animal has a name and a sound, so does each letter”.

If you would like more information about teaching your child the sounds associated with each letter, see our article,‘How To Teach Phonics‘.

When you’re teaching the sounds to your child, or helping them read their first words, if they say the name of a letter, don’t make a big deal about it. Just say: “yes, that’s its name, and what sound does it make?”

If you keep reinforcing that it’s the sound you want them to say they will soon get the idea. Also, try to avoid mentioning the letter names again yourself until your child is reading fluently. If they have any electronic toys that use the letter names, put them out of the way for a while.

Further Information…

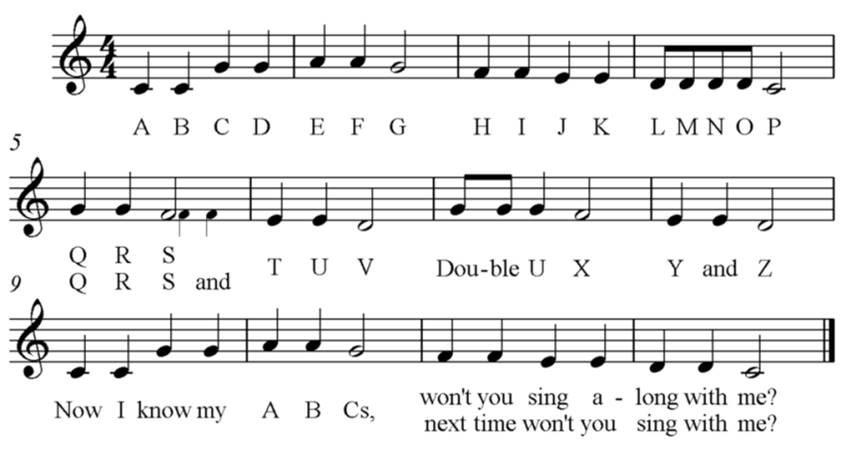

You might also find this article from the excellent Spelfabet site interesting: Let’s not sing our ABCs.

John Walker, who developed the Sounds-Write reading programme has also written an article on learning letter names vs sounds.

And the renowned reading researcher Tim Shanahan gives a contrary view in this article.

If you would like to access some free resources and activities to help your child with other aspects of early literacy, click on the following link for our article on phonological/phonemic awareness activities for parents and teachers.

References:

- Project Follow Through, National Institute for Direct Instruction: https://www.nifdi.org/what-is-di/project-follow-through

- Englemann, S. (1986), Teach Your Child to Read, Simon & Schuster.

- McGuinness, D (2004) Early Reading Instruction: What Science Really Tells Us about How to Teach Reading, MIT Press.

- McGuiness, D. A Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code, RRF Newsletter 49: http://www.rrf.org.uk/archive.php?n_ID=95&n_issueNumber=49

- Piasta, S.B., Purpura, D.J., & Wagner, R.K. (2010). Fostering alphabet knowledge development: A comparison of two instructional approaches. Reading and Writing, 23, 607–626. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885812/

- Ellefson, M.R., Treiman, R., & Kessler, B. (2009). Learning to label letters by sounds or names: A comparison of England and the United States. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102(3), 323–341. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2671388/

- The Fragility of the Alphabetic Principle: Children’s Knowledge of Letter Names Can Cause Them to Spell Syllabically Rather Than Alphabetically, Treiman R1, Tincoff R: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9073380

- Clarke, LK (1988) Invented Spelling Verses Traditional Spelling in First Graders’ Writings

- (Treiman, Stothard, & Snowling(2013). Instruction Matters: Spelling of Vowels by Children in England and the US.

- Solity, J. (2003) Teaching Phonics in Context: A Critique of the National Literacy Strategy (page 20, section 6.7).

- Willingham, D (2009), Why Don’t Students Like School?, Jossey-Bass.

- Clark, R. Putting Students on the Path to Learning.

- THE BRAINS CHALLENGE, CHILDREN OF THE CODE: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/index.htm

- Gathercole, S and Galloway, T, Understanding working memory a classroom guide: https://www.york.ac.uk/res/wml/Classroom%20guide.pdf

- Solity, J. (2003) Teaching Phonics in Context: A Critique of the National Literacy Strategy (page 28, section 9.9)