What Is It and Should I Encourage My Child to Use It?

Invented spelling is the favourite strategy of some educators, but others dispute its effectiveness. Find out if this technique could help your child…

In our spelling with phonics article, we suggested that in order to develop good spelling skills, children must first grasp the basic principles of our alphabetic spelling system. This knowledge can be learned most efficiently from a good phonics programme.

We looked at how children’s spelling skills can be improved further in our articles ‘Teach Your Child to Spell More Complex Words’ and ‘Spelling Strategies for Kids’. You might find it helpful to read these earlier articles if you haven’t already done so.

Invented spelling is another approach that’s recommended by some educators, but its effectiveness is disputed amongst different groups of academics and teachers. We’ll look at some of the arguments for and against its use in this article and suggest some ways of using the approach more effectively.

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Disclaimer: We support the upkeep of this site with advertisements and affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you click on the ads or links or make a purchase. There is no additional cost to you if you choose to do this.

Contents:

- What is Invented Spelling?

- Why Devote a Whole Article to Invented Spelling?

- The Pros and Cons of Invented Spelling

- “Invented Spelling Allows All Students to Communicate in Writing and Express Themselves More Creatively.”

- “Children Are More Motivated to Write When They Are Allowed to Use Invented Spellings.”

- “Invented Spelling Allows Children to Practise Their Phonics Skills and This Makes Them Better Spellers.”

- “Invented Spelling Can Help Parents or Teachers Discover Important Information About a Child’s Knowledge of Spelling.”

- “Invented Spelling is Better Than Formal Instruction Because It Allows Children to Work Through the Natural Stages of Development”

- What Do We Think About Invented Spelling?

- “My Child Hasn’t Had Any Spelling Instruction, Should I Stop Them From Doing Extended Writing?”

- Alternatives to Extended Writing

- Further Information

- References

Summary

- Invented spelling is a term used in schools when children are told to make up their own spellings for words rather than asking an adult or using a dictionary.

- Invented spelling writing activities could be helpful for children who’ve already had a reasonable amount of direct phonics spelling instruction. These activities can provide children with the opportunity to practise the phonics skills they’ve learned in a real context.

- Young children should not be encouraged to write extensively using invented spelling before they’ve had any real spelling instruction.

- Children make better progress when writing and spelling are taught explicitly and systematically. They don’t need to discover how to spell themselves or go through developmental stages.

- With proper guidance, children can learn to spell words correctly as soon as they learn how to read them.

- Always give feedback on written work and point out spelling mistakes, but do this sensitively and tell your child that they will improve with more practice.

- Left unchecked, the same errors are likely to be repeated every time they write, and this makes it more likely that a child will remember the incorrect spellings in the long-term.

- Show your child how to construct simple sentences, then more complex sentences before you encourage them to do extended writing tasks.

What is Invented Spelling?

The basic idea behind invented spelling is that children are encouraged to make up their own spellings for words, rather than asking an adult or using a dictionary. They’re expected to make an educated guess based on any knowledge they have about letters and spellings at the time.

In some schools, kids are given written work even before they’ve mastered the basics of reading. The emphasis is on purposeful writing: writing that has some meaning or importance to the children.

Little concern is given to the potential complexity of the words that might be needed in a written assignment because children can invent their own spellings for those words. So, in their first term at school, kids might be encouraged to write about virtually anything:

- messages or letters to friends and relatives

- describing the foods they would like to eat at a party

- shopping lists, or lists of presents they would like for a birthday,

- stories about their recent experiences, or

- their plans and feelings about a future event such as a holiday,

- fictional stories, poems and songs.

In schools that promote invented spelling, children are given frequent opportunities to write in lessons and parents are told to encourage writing at home so it becomes part of a normal daily routine.

Some educators suggest that you shouldn’t correct your child’s spelling or worry if you can’t read their writing. Instead, you should praise your child for coming up with an imaginative story or interesting details.1

Why Devote a Whole Article to Invented Spelling?

We decided to explore the subject in some depth because it’s a controversial topic and we want you to be able to make an informed decision about whether or not to use invented spelling with your own children.

Some academics, such as Dr. Louisa Moats, argue that invented spelling is beneficial because it gets kids to exercise their phonemic awareness.2 Others, such as Professor Dianne McGuinness, say that it’s more likely to confuse children and delay their progress.

Maeve Maddox, a former teacher and self-proclaimed “American English Doctor”, is a strong critic. She defines invented spelling as:

“A child’s effort to spell words in a written assignment before being given adequate classroom instruction by the teacher.” 3

However, for every critic, there are others who rave about the benefits of invented spelling. For example, Margaret Phinney, a teacher and independent reading consultant, asserts:

“… it is essential to encourage writing behavior as early as possible. … Writing has become too important for us to waste precious time waiting for our writers to first become perfect spellers.” 4

Phinney provides examples of a child’s progress as she moves from a barely recognisable statement in a block of letters at the start of first grade:

“IMEFPDEVLDK.”

(I’m afraid of the dark)

– to more recognisable words in a sentence a few months later:

“I am GoiNg to aftar SKol GimNastikS lam IGSatiD VaRe VaRe IGSatiD I hoP that SKol is ovar soN I hoP We Do the RoP clim I hiK it wil be faN vare fan.”

Similarly, Dr Richard Gentry, a researcher and author of a book on childhood literacy, strongly promotes invented spelling.5

Gentry mentions a study that found the sophistication of children’s invented spellings in kindergarten was a good predictor of their subsequent reading and spelling in Grade 1.6

The Pros and Cons of Invented Spelling…

We’ve listed some of the common arguments that are put forward to support the use of invented spelling below, along with a number of counterarguments against its use.

If you would rather skip the pros and cons, just read the summary of what we think about invented spelling at the start of this article.

“Invented Spelling Allows All Students to Communicate in Writing and Express Themselves More Creatively.”

Students can use any word in their spoken vocabulary if they don’t have to worry about spelling. This means they can write about anything that’s important or relevant to them at the time and express how they feel.

In contrast, when children are restricted to using only the words they can spell, this limits what they can write about, stifling their creativity.

Counterarguments:

While it’s true that invented spelling can give young children more freedom in their writing, it’s important to remember that writing isn’t the only way children can communicate and express their creativity.

Children can also be encouraged to talk about the things that are important to them and they can illustrate their ideas by drawing pictures or through craftwork. Our distant ancestors learned to tell elaborate stories using spoken words and pictures long before the invention of writing.

Some people also argue that encouraging children to write excessively in school can limit the time available to give them proper instruction in spelling, punctuation, grammar and structure. So, although they might be able to write more freely in the early stages, children could struggle to express themselves articulately once they reach the stage where correct spelling and organisation really matter.

In contrast, children who’ve been given more instruction and less writing in the early stages end up being able to use a greater range of words and express themselves more articulately in their writing when they’re older. They can also be more creative because, as confident spellers, they can focus more of their attention on the composition of the story.

“Children Are More Motivated to Write When They Are Allowed to Use Invented Spellings.”

Since children can write about anything that’s important or relevant to them (without worrying about correct spellings), they quickly learn that the real purpose of writing is to produce interesting and useful content.

Consequently, they are more likely to think of writing as an enjoyable way of expressing their thoughts. Since they enjoy it and get praised for their efforts, this encourages them to write more.

Children who are taught to use correct spellings for all the words in their writing find it a much more laborious task. They either become dependent on adult assistance or resort to using the more limited number of words they can spell correctly. As a result, they’re more likely to produce content that is dull.

Proponents of invented spelling sometimes cite studies that show children write more when they are allowed to use invented spelling.7

Counterarguments:

There seems little doubt that children are more likely to be motivated when they are writing about things that are important or relevant to them.

However, some educators have found that lots of young children consider any type of extended writing to be a laborious task because producing high quality written work requires more than just the ability to spell. 8

Composing a good piece of writing also requires good concentration and well developed fine motor skills. Many young children haven’t fully acquired these attributes, so they find it a struggle to form their letters.

After spending a considerable amount of time getting their thoughts down on paper, some children can’t even read their own writing, which can make them feel less motivated about writing in the future.

To produce an extended piece of writing of reasonable quality, children also need an understanding of the structure of sentences and paragraphs. This requires knowledge of the correct use of punctuation, connectives, openers and the organisation of ideas so they can be linked together to form a coherent passage.

As we mentioned previously, some people argue that encouraging children to write excessively can limit the time available to give them proper instruction on how to write.

Some teachers have reported that many children who’ve been encouraged to write spontaneously with minimal instruction find it difficult to write a coherent paragraph, let alone a decent essay, and these problems persist all the way through their secondary school years. 9

You might have noticed that these counterarguments don’t really challenge the value of invented spelling itself, but rather the idea that we should be expecting children to write at length without much guidance from an early age.

“Invented Spelling Allows Children to Practise Their Phonics Skills and This Makes Them Better Spellers.”

When children have to come up with their own spellings for words it makes them think about the sounds in the words and the letters that could be used to represent those sounds. This reinforces children’s understanding of the connection between letters and sounds (which is what phonics is all about).

As a result, children who are encouraged to invent their own spellings learn to experiment with spelling patterns and make faster progress than children who don’t use invented spelling. This has been confirmed in academic studies. 10

Counterarguments:

Proponents of invented spelling often mention a study where researchers compared students who were encouraged to use invented spelling with those who were not. The results of this investigation did show that children who used invented spelling did better in spelling tests at end of the study. 10

However, neither group in the study were given any formal spelling instruction. Children in the control group simply copied the spellings of words supplied by the teacher or used a primary dictionary. Furthermore, neither group received any systematic phonics instruction. All of the children were following a basal reading programme which promoted “a reliance on processing words by their visual cues rather than by phonic analysis.”

So, in the absence of any systematic phonics or spelling instruction, it does seem that invented spelling has some advantages over directly copying words. And it seems likely that children do exercise their phonics skills when they invent their own spellings for words.

However, this study doesn’t show that children encouraged to use invented spelling would have an advantage over children who were given direct, systematic phonics instruction in spelling and reading.

In fact, quite the opposite seems to be true:

One U.S. study compared the spelling in third-grade children who had had whole-language instruction with the spelling of third-grade children who had received phonics instruction. Invented spelling is encouraged by whole-language advocates, yet in this study, the phonics instructed children were the better spellers. 11

And this isn’t just an isolated example. According to Dr. Patrick Groff, Professor of Education Emeritus at San Diego State University:

“The great preponderance of empirical evidence on children’s spelling development indicates that children learn to spell correctly faster if taught to do so in a direct and systematic way.” 12

Dr. Groff’s view is supported by the conclusions of Government reviews done in the US, Australia and the UK, as we outlined in our spelling with phonics article.

Even Dr. Louisa Moats, who supports the use of invented spelling, has said that invented spelling shouldn’t replace organised instruction.

So it would appear that children don’t have to use invented spelling to practise their phonics skills if they’re already getting plenty of practice using phonics through a detailed and systematic programme of instruction.

We’ve outlined how this can be done effectively in the first 3 articles about spelling in this section.

“Invented Spelling Can Help Parents or Teachers Discover Important Information About a Child’s Knowledge of Spelling.”

Dr. Louisa Moats, a respected academic who has produced many influential papers and articles about literacy has stated:

“If we know how to look at a child’s spelling we can tell what that child understands about word structure, about speech sounds, about how we use letters to represent those. And as it turns out ah, anything that is going to cause trouble with a child’s reading will show up even more dramatically in the child’s spelling and writing.” 2

Counterarguments:

What Dr. Moats says is true, but information about a child’s spelling ability can be obtained more easily and efficiently using simple dictated spelling tests.

Furthermore, gaining knowledge about a child’s misunderstandings is only really useful if the teacher is able to provide detailed feedback and help the child to make corrections.

Encouraging beginning readers to write extensively using invented spellings means they will inevitably use many words that are beyond their current level of spelling ability. Consequently, the sheer volume of errors will make a teacher’s job more difficult.

Consider this excerpt from a first grader story published on the ‘Great Schools’ website:

“Ther ouns was two flawrs. Oun was pink and the othr was prpul. Thae did not like ech athr becuse thae whr difrint culrs. Oun day thae had a fite.”

In this short excerpt, there are far more mistakes than there are correct spellings. Suppose a class of children at a similar level of development were to write an average of 40 words each; it’s likely they would spell around half of the words incorrectly. 20 mistakes each in a class of 30 children would amount to a total of 600 incorrectly spelled words.

If a teacher spent just 1 minute helping a child to derive the correct spelling for each word they got wrong that would add up to 20 minutes per child. For a class of 30 children that would amount to 10 hours of individual teacher time, which is approximately 2 whole school days!

So in a classroom environment, it’s unlikely that the teacher would have time to check and explain each word. Consequently, invented spelling errors might get reinforced with subsequent practice.

However, for someone doing individualised tuition with their child at home, providing quality feedback would be much more manageable.

“Invented Spelling is Better Than Formal Instruction Because It Allows Children to Work Through the Natural Stages of Development”

Some educators believe that children move through a number of progressive stages as they develop their own theories about how writing and spelling work. 13

Reading consultant Margaret Phinney compares the process of learning to spell to learning to walk or talk. 4

In each case, children start off with clumsy imitations of the real thing and gradually refine their efforts until they become proficient. Educators with this view see spelling as a natural process with distinct phases of development:

- In the early stages, children have no idea what letters are for, but they might be able to produce some recognizable letters amongst their drawings or scribbles.

- Gradually, they show some understanding of the link between letters and sounds, but they might use abbreviated versions of words at first.

- Subsequently, they show a much greater understanding of phonics and their written words are more recognizable, even if the spellings are unconventional.

- Eventually, they learn to use the correct letter combinations as their exposure to standard spelling increases through reading.

According to Phinney and many other educators, children need to work through each of these stages in the same way as they have to work through the developmental stages of walking and talking.

Some experts believe that an early emphasis on the mechanical aspects of spelling could inhibit a child’s developmental growth. 14

Counterarguments:

The idea that learning to spell is a natural developmental process isn’t accepted by all educators. For example, Alison Clarke, the author of the Spelfabet website has made the following comment:

“Saying there are developmental stages in spelling is a bit like saying there are developmental stages in learning to cook, fix a car or program a computer.” 15

Clarke suggests that while it is possible to pick up the basics of some of these things by observing competent adults, children learn faster when they are taught skills in a step-by-step, systematic way. The same is true for spelling according to Clarke.

As we’ve mentioned in one of our other articles, many developmental theories are based on outdated assumptions about the way young children learn, rather than rigorous scientific studies.

Dr. Patrick Groff, Professor of Education Emeritus at San Diego State University, is also sceptical about the importance of children moving through natural developmental stages. He has stated:

“ …the supposed necessity of replacing direct and systematic spelling instruction with invented spelling has not been experimentally verified.” 12

Professor Dianne McGuinness, a cognitive psychologist and author of several books on literacy has been another prominent critic of the developmental model that underpins invented spelling.

What Do We Think About Invented Spelling?

We believe that invented spelling has some potential benefits and some drawbacks, depending on how it’s used. Invented spelling writing activities could be helpful for children who’ve already had a reasonable amount of direct phonics-based spelling instruction.

Writing activities can provide children with the opportunity to practise the phonics skills they’ve learned in a real context and they can also be used as a way of assessing a child’s progress in learning the words they’ve been taught.

Encouraging children to figure out their own spellings when they’re writing makes them think about the sounds in words and about the letters which can be used to represent those sounds. Children are less likely to think about letter/sound relationships if they rely on an adult to spell every word for them, or copy directly from a dictionary.

So we’re inclined to agree with Dr. Louisa Moats’ point that invented spelling can be beneficial because it gets kids to exercise their phonemic awareness.

However, we aren’t convinced that young children should be encouraged to write extensively using invented spelling before they’ve had any real spelling instruction. While this may stimulate their creativity to some extent, there are other ways that young children can express their creative thoughts.

We don’t think independent writing using invented spelling is a very efficient way for beginning readers to learn to spell for the following reasons:

- Children are less likely to figure out common spelling patterns without any guidance.

- They will inevitably make a huge number of errors. Ignoring these errors makes it more likely they will be repeated, and correcting too many errors could be demoralising for a child.

- A vast number of errors can also make it difficult to find something to focus on for improvement.

- Really bad spelling and poor writing can make it difficult for a teacher or parent to figure out what the child has written (some young kids can’t even read their own writing).

- Providing some direct instruction on spelling and sentence structure is a more productive use of time.

Some educators claim that many children can learn to spell using invented spelling writing activities without any spelling instruction, and we’re sure they are being honest in their evaluations. However, this doesn’t mean it’s the most efficient way to learn.

Extensive reviews commissioned by the Governments of several English speaking countries have concluded that children make better progress when writing and spelling are taught explicitly and systematically, as we outlined in our spelling with phonics article.

There are a number of other claims made by invented spelling advocates that we’re inclined to disagree with, as we’ve outlined below:

We don’t believe children need to progress through developmental stages in spelling, this only happens in the absence of adequate instruction…

With proper guidance, children can learn to spell simple words correctly as soon as they learn how to read them. We’ve described how this can be done in our spelling with phonics article. And children can learn to spell more complex words correctly as their phonics skills increase as we described in a subsequent article.

We haven’t seen any evidence to support the claim that teaching young children how to spell can inhibit their developmental growth…

In fact, we taught both of our daughters how to read and spell when they were very young and they’re both greatly exceeding expectations for their age in reading, writing and spelling according to school assessments.

In her article about invented spelling, Maeve Maddox compares examples of work from children who’ve been encouraged to use invented spellings with those given early spelling instruction. The differences are striking.

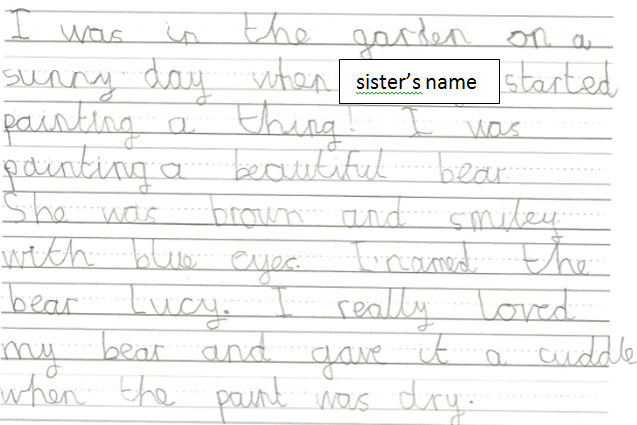

We’ve included an example of our eldest daughter’s writing below. She was only 5 years old when she wrote it and we didn’t give her any help with the spellings. Nor did she use a dictionary:

Compare this with the example below from a first grader encouraged to use invented spelling without any spelling instruction:

“I am GoiNg to aftar SKol GimNastikS lam IGSatiD VaRe VaRe IGSatiD I hoP that SKol is ovar soN I hoP We Do the RoP clim I hiK it wil be faN vare fan.” 4

Or the excerpt below from a first grader’s story published on the ‘Great Schools’ website:

“Ther ouns was two flawrs. Oun was pink and the othr was prpul. Thae did not like ech athr becuse thae whr difrint culrs. Oun day thae had a fite.”

Our daughter went on to get full marks in her writing SAT (Standard Attainment Test) when she was 7, and she has been praised for the quality of her writing by all of her teachers as she has moved through the school. So it’s clear that her developmental growth hadn’t been inhibited by the early spelling instruction she received from us.

We agree with Maeve Maddox’s point that expecting children to learn to spell in a similar way to how they learn to walk and talk is based on a misconception…

As we discussed in our article ‘Can Children Teach Themselves to Read?’, there are some key differences between verbal and written communication:

For most of human history, the vast majority of people have been illiterate, so reading and writing haven’t been a natural part of our social development in the same way that spoken language has.

Keith Stanovich, Professor of Applied Psychology at Toronto University, has written:

“the idea that learning to read is just like learning to speak is accepted by no responsible linguist, psychologist, or cognitive scientist in the research community.” 16

Some invented spelling advocates advise that you shouldn’t correct your child’s spellings and this alarms us…

Correcting spelling errors is a form of feedback and providing feedback has been consistently shown to be one of the most important aspects of teaching and learning. 17

If a child isn’t shown what is correct and what isn’t, how will they know what they need to work on? Left unchecked, the same errors are likely to be repeated every time they write, and this makes it more likely that a child will remember the incorrect spellings in the long-term.

How you should respond to spellings errors depends on the number of errors your child has made:

If your child has made a huge number of errors in an extended piece of writing then this is an indication that the task they’ve been given is beyond their current level of ability.

In cases like this, it probably isn’t worth spending time correcting every word because your child probably hasn’t got enough phonics knowledge to understand the feedback. What they need is several weeks of direct spelling instruction (of the type we’ve indicated in the first 2 articles in this series on spelling).

Once your child has shown some progress in their spelling skills, they could be asked to do another piece of writing, but it would probably be better to start off with a task that is less open-ended (see the section on alternatives to extended writing below).

For children who’ve only made a moderate number of errors, the errors should be highlighted so they can be corrected.

Feedback about spelling errors shouldn’t demotivate a child if it’s done in the right way – it’s important to let children know that making mistakes is a natural part of learning and nothing to be ashamed of. Pointing out spelling errors is no different than pointing out mathematical errors when children are doing sums.

When you check your child’s work, make sure you give them feedback on what they have done well in addition to pointing out their errors.

For example, if a child spells the word ‘elephant’ as ‘elefant’, they’ve got most of the letters correct and they should get some recognition for this. They just need to be reminded that sounds can sometimes be represented by different letters and in this case, the ‘f’ sound should be represented by ‘ph’ as it is in ‘dolphin’.

When providing feedback, try to use language like: “you haven’t quite got the hang of this word yet, but with a bit more practice you’ll get there soon”. This kind of narrative encourages children to develop what Psychologist Carol Dweck calls a “Growth Mindset”. Basically, this is the belief that their abilities aren’t fixed in stone, they can develop if they make an effort to improve.

“My Child Hasn’t Had Any Spelling Instruction, Should I Stop Them From Doing Extended Writing?”

If your child really wants to write about something, we don’t think you should try to stop them. It seems wrong to stifle a child’s enthusiasm for writing even if they don’t yet have the knowledge and skills to do it well.

At the same time, we don’t think children should be pushed into writing at length before they’ve learned the basics of how our alphabetic spelling system works.

If your child does some independent writing, we think it’s important that you give them some feedback about what they’ve written.

Praise their efforts and tell them how impressed you are. If they’ve made a large number of spelling errors, don’t point each one out or circle them with a pen because this could be demoralising. Instead, you might want to say that you’re so impressed you would like to copy out their work so they can see how it would look with ‘grown-ups’ spellings.

You might then ask them to compare their version with yours so they can see how the words look when they are spelled correctly. You could also explain the spellings for one or two of the incorrect ones (going through every spelling error could be laborious if there are a lot).

If they hardly spell anything right, praise them for any words where they get close to the correct spelling. They could even copy out your correct version if they wanted to.

Alternatives to Extended Writing

If your child was learning to play a musical instrument, it would be unlikely that the teacher would give them an extended piece of music to play before they had been given any instruction.

They would first need to learn how to play the different notes and they would need to develop a basic understanding of the relationships between them. The teacher would gradually introduce them to concepts like octaves and scales and they would build up from playing short sequences of notes to simple compositions.

Similarly, if you want your child to develop their writing skills, they first need to develop a basic understanding of the structure of sentences and paragraphs. Like most skills, this is best taught in an incremental way…

Sue Hackman, a former English teacher and Chief Adviser on School Standards at the Department for Education in the UK, says that pupils need coaching in something she calls ‘micro-writing’ before they’re asked to do extended writing.

This is writing that’s focused at sentence length, or perhaps short paragraphs.

“Micro-writing takes a sentence, highlights its grammatical structure and then invites pupils to borrow the grammar to write a similar sentence of their own. It gives them instant access to complex sentence structures they are unlikely to stumble upon without this prompt. The activity increases their sentence stock and increases their confidence in construction of complex sentences.” 18

It takes children some time to develop the spelling skills needed to write out even simple sentences independently. However, you could get your child to verbalise sentences and write out the difficult words for them, leaving gaps for them to fill in the words they should know.

Another strategy is to start off with a sentence that has been jumbled so the words are in the wrong order. Ask your child to write out the words in the correct order to form a proper sentence (or cut out the words and ask your child to put them in the right order). For example, the words:

green The in had frog skin. the pond

Could be made into the following sentence:

‘The frog in the pond had green skin.’

You could point out that the capital letter and full stop give a clue about the first and last words in the sentence.

If a sentence like the one above proves too difficult, start off with shorter sentences such as:

‘The frog had green skin’ or ‘Monkeys eat bananas’.

There are several more examples in this Pinterest link.

Once your child has got the hang of exercises like this one, you could help them to make up a sentence of their own about a different animal or object.

Point out that for a sentence to work it needs to tell us what a person, animal or thing is doing or being like.

For young children, you probably don’t need to get into the correct grammatical terms like subjects, objects and verbs right away, just showing examples will help them get the idea:

- The girl ran down the hill.

- The cat sat on the mat.

- The monkey was funny.

- The puppy was nervous.

Once they’ve got the hang of simple sentences you can gradually show them how to build up more complex sentences:

- The little girl ran down the hill as quickly as she could.

- The black cat sat on the mat licking its paws.

- The cheeky monkey pulled a face and it was funny.

- The tiny puppy was nervous when the big dog came close.

And then move on to linking sentences together to make paragraphs.

Showing children how to form simple sentences, then more complex ones and then paragraphs helps them to develop a better understanding of how an extended piece of writing is composed.

This more gradual and systematic approach is likely to produce better results in the long-run than asking them to produce lengthy pieces of writing without any guidance.

Click here if you want to review the summary of this article or see below for other useful links.

Further Information…

If you want more guidance about teaching your child to spell or write, see the other articles in this section.

The Spellzone website is a fantastic online resource suitable for 7-year-olds to adults. It has some great word lists, activities and spelling games and you can also access a spelling ability test and a complete spelling course from the site. The course is suitable for anyone wanting to learn British or American Spelling.

Click here if you would like more information about teaching your child to read.

References:

- com. The Dos and Don’ts of Invented Spelling. Last accessed July 2018: https://www.education.com/magazine/article/The_Dos_and_Donts_Invented/

- Invented Spelling (Branford, Connecticut), Launching Young Readers series, Writing and Spelling, Reading Rockets, Last Accessed July 2018: http://www.readingrockets.org/shows/launching/writing#trans_invented

- Maddox, M. Invented Spelling, Basic Literacy For All, American English Doctor: http://americanenglishdoctor.com/wordpress/invented-spelling

- Phinney, M. Invented Spelling, The Natural Child Project, Last accessed July 2018: http://www.naturalchild.org/guest/margaret_phinney2.html

- Gentry, R. (2017) Landmark Study Finds Better Path to Reading Success, Raising Readers, Writers and Spellers, Psychology Today (last accessed 3/3/2018): https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/raising-readers-writers-and-spellers/201703/landmark-study-finds-better-path-reading-success

- Ouellette, G., & Sénéchal, M. (2017). Invented spelling in kindergarten as a predictor of reading and spelling in Grade 1: A new pathway to literacy, or just the same road, less known? Developmental Psychology, 53(1), 77-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dev0000179

- See, for example, Clarke, LK (1988) Invented Spelling Verses Traditional Spelling in First Graders’ Writings

- See, for example, Alison Clarke’s article about creative writing in her ‘Spelfabet’ site: http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2013/05/creative-writing/

- Burkard, T. Invented Spellings, RRF Newsletter 53: http://www.rrf.org.uk/archive.php?n_ID=52&n_issueNumber=53

- Clarke, LK (1988) Invented Spelling Verses Traditional Spelling in First Graders’ Writings

- Bruck, M., Treiman, R., Caravolos, M., Genesee, F., & Cassar, M. (1998). Spelling skills of children in whole language and phonics classrooms. Applied Psycholinguistics, 19, 669–684.

- Groff, P. (2014), A Critique of Inventive Spelling, National Right to Read Foundation:http://www.nrrf.org/learning/critique-inventive-spelling/

- Cn u rd ths? A guide to invented spelling, GreatSchools.org: http://www.greatschools.org/gk/articles/invented-spelling/

- Lutz, E. Invented Spelling and Spelling Development, Reading Rockets: http://www.readingrockets.org/article/invented-spelling-and-spelling-development

- Clarke, A. Words Their Way, Spelfabet, last accessed July 2018: http://www.spelfabet.com.au/2013/06/words-their-way/#more-9273

- Stanovich, Keith E. Progress in Understanding Reading, 415. New York: The Guilford Press, 2000.

- Petty, G. (2006), Evidence Based Teaching, Nelson Thornes.

- Hackman, S. (2014) THERE’S MORE TO EXTENDED WRITING THAN LENGTH.