Phonemic awareness explained in plain English. Examples of phonemic awareness skills and teaching tips…

Contents:

- What Does Phonemic Awareness Mean?

- What Are Examples of Phonemic Awareness Skills?

- What’s the difference Between Phonemic Awareness and Phonological Awareness?

- Why is Phonemic Awareness Important?

- What’s the Difference Between Phonics and Phonemic Awareness?

- What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?

What Does Phonemic Awareness Mean?

A simple definition of phonemic awareness would be…

‘Knowing that words are made up of individual sounds.’

More thorough definitions of phonemic awareness usually mention…

‘The ability to hear, identify and manipulate phonemes in spoken words.’

The definitions above make more sense when you look at examples of phonemic awareness skills. These can range from recognising that some words start with the same sound to being able to identify all of the sounds in more complex words such as ‘playground’, /p/-/l/-/ay/-/g/-/r/-/ou/-/n/-/d/.

Children with advanced levels of phonemic awareness can also add, remove and substitute sounds to create new words. For example, they would be able to:

- Add a /p/ sound to the end of the word ‘clam’ and recognise that the new word is ‘clamp’.

- Remove the /c/ sound from ‘clamp’ to make ‘lamp’.

- Swap the /a/ sound in ‘lamp’ for an /u/ sound and identify the new word as ‘lump’.

The short video below explains phonemic awareness:

We’ve provided a more comprehensive list of phonemic awareness skills in the section below…

What Are Examples of Phonemic Awareness Skills?

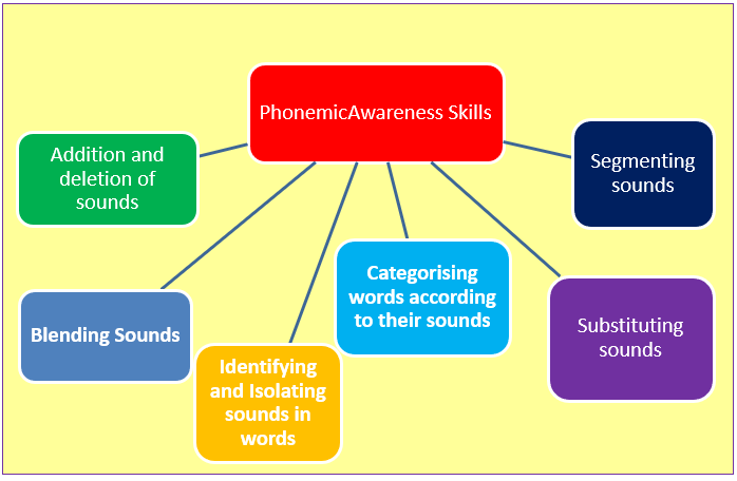

Descriptions of phonemic awareness skills can vary, but they are generally broken down into some or all of the following aspects, which might also be used to assess a child’s phonemic knowledge*:

Identifying and Isolating Sounds in Words:

- The ability to say what sound a word starts with. For example, “What’s the first sound in the word ‘mat’?”

- The ability to recognise when words in a phrase or sentence start with the same sound (alliteration). For example, understanding that the phrase ‘Six slimy slugs’ is an example of alliteration whereas the phrase ‘Six green frogs’ isn’t.

- The ability to come up with examples of words that start with the same sound. For example, “Can you think of any other words that we could add to ‘Six slimy slugs’ that start with the same sound?” Here, a student with good phonemic awareness might come up with something like ‘Six slimy, squishy, slithering slugs’. However, the ability to do this would depend on a child’s vocabulary as well as their phonemic awareness.

- Recognising words that end with the same sound. For example, “Which of these words end with the same sound – ‘pin’, ‘tin’, ‘sat’?”

- The ability to come up with examples of words that end with the same sound. For example, “Can you tell me another word that ends with the same sounds as ‘man’?”

- Recognising words that have the same middle (vowel) sound. For example, “Which of these words have the same middle sound – ‘beg’, ‘pen’, mix?”

- The ability to come up with examples of words that have the same middle sound. For example, “Can you tell me another word that has the same middle sound as ‘man’?”

- The ability to say precisely where a particular sound appears in a word. For example, “Where does the /o/ sound appear in the word ‘dog’ – is it at the beginning, in the middle or at the end?”

Categorising Words According to Their Sounds:

- Being able to recognize a word in a series is an odd one out because it starts with a different sound. For example, “Which of these 3 words starts with a different sound: ‘bat’, ‘cup’, ‘bag’?”

- Grouping words based on sounds in other positions. For example, “Put the following words into pairs based on their middle sounds: cat, big, fit, tap, map.”

Blending Sounds

- The ability to combine individual sounds together to make a recognizable word (see our article on blending). For example, listening to the sounds /c/ – /a/ – /t/ spoken separately and then being able to merge them together to make the word ‘cat’.

Segmenting Words

- Being able to split a spoken word up into its individual sounds (see our article on segmenting). For example, saying the sounds /f/ – /i/ – /sh/ after hearing the word ‘fish’.

Substituting Sounds

- The ability to swap one sound in a word for another to make a new word. For example, “What word would we get if we swap the /c/ sound in ‘cat’ with a /b/ sound?” (bat). This task could be extended by asking what words could be made by swapping the end or middle sounds.

Addition and Deletion of Sounds

- The ability to add or remove sounds to make new words. For example, “what new word would we get if we add the /c/ sound to the word ‘lip’?” (clip).

Or “If we take the /f/ sound away from ‘frock’, what new word would we get?” (rock).

*Reference: Hempenstall, K. (2014), Phonemic Awareness: Yea, nay?

- The ability to add or remove sounds to make new words. For example, “what new word would we get if we add the /c/ sound to the word ‘lip’?” (clip).

A Summary of Phonemic Awareness Skills…

What’s the difference Between Phonemic Awareness and Phonological Awareness?

The basic difference is that phonological awareness is an expression used to describe a broad range of auditory/oral language skills, whereas phonemic awareness describes a specific set of skills within that range. So phonemic awareness is a sub-skill of phonological awareness.

Phonological awareness is an ‘umbrella term’ in the same way that literacy is an umbrella term that’s used to broadly describe a person’s abilities in reading and writing.

A child with a basic level of phonological awareness can recognise that there are different sound components in spoken language.

For example, they might understand that sentences are made up of individual words and that words are made up of syllables. They might also be able to identify words that rhyme.

Phonemic awareness is often considered to be a more advanced element of phonological awareness. Children with this ability can break words down into sound units that are smaller than syllables. These sound units are known as phonemes.

There are a variety of phonemic awareness skills and we described these in the previous section of this article.

It’s understandable that people often confuse phonemic awareness with phonological awareness because the two terms are closely related and even some researchers use the expressions interchangeably.

To summarise, phonemic awareness is just one part of a broad range of language skills known as phonological awareness.

The short video below explains the relationships between the terms quite clearly:

Why is Phonemic Awareness Important?

Phonemic Awareness and Reading Success

A variety of studies have shown that phonemic awareness is a strong predictor of later reading success or difficulty*. In fact, it seems to be more important than a child’s IQ, vocabulary, or listening comprehension#.

*See, for example, Hempenstall, K. (2014), Phonemic Awareness: Yea, nay? , Also, US National Reading Panel (2001) ‘Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis’.

#Sensenbaugh, R. ABCs of Phonemic Awareness

Without phonemic awareness, it’s impossible to grasp the idea that words are composed of different sounds. Children who lack this skill find it very difficult to learn to read or spell because letters represent the sounds in words.

The phonemic awareness skill of blending is especially important for children who are learning to read using phonics.

Phonemic Awareness and Spelling

Phonemic awareness skills could be more important for spelling than visual memory*.

*American Educator, Winter 2008-2009, How Words Cast Their Spell

The ability to segment words into their constituent sounds can help children remember the sequence of letters in a word (as long as they know the letters that represent each sound).

Without phonemic awareness, children have to memorise the spellings of words by rote, which is similar to learning random string of numbers. This is a very inefficient way of learning.

What’s the Difference Between Phonics and Phonemic Awareness?

Phonemic awareness is an auditory skill that’s focused on identifying the individual sounds in spoken language. It can be practised and assessed by speaking and listening without looking at any printed words or letters.

Phonics is a way of applying a child’s knowledge of phonemic awareness to printed words when they are learning to read and spell. The relationships between sounds and letters are emphasised in phonics.

Kids are taught the alphabetic code when they start phonics instruction. This means they learn that individual letters and groups of letters in words represent sounds in spoken language.

As a result, phonics allows children to understand the relationship between spoken and written words so they can transfer their knowledge of the sounds in spoken language to written language.

It would be impossible to grasp phonics without developing some phonemic awareness, but it’s not essential to do phonemic awareness training before phonics instruction.

This is because phonics instruction helps children develop phonemic awareness. See the section below for more information about this.

What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?

Extensive reviews of the research indicate that phonemic awareness is best taught using letters from the start rather than as a stand-alone verbal and auditory exercise.

The focus should be on using the common sounds associated with each letter rather than letter names. There is also evidence that the main emphasis should be on blending and segmenting skills since these have the greatest impact on reading and spelling.

See below for more information on each of these points…

Should Phonemic Awareness be Taught Without Letters?

Some educators claim that it’s important to teach phonemic awareness as an isolated speaking and listening skill before children are introduced to any letters or phonics instruction.

For example, we found the following quotes online from reputable websites:

“Ideally we should not teach letters until a person can hear individual sounds in a word.”

The Specific Learning Difficulties Association of South Australia.

“Many kindergarten and first-grade programs begin reading instruction with phonics.…This approach can be hard for some students. It can make the process of learning to read much more challenging.

“Phonemic awareness should first be taught without any letters using blocks or chips to represent the sounds and make them salient to the child. Children need to learn to hear those sounds without being confused by the letters that correspond with them.”

However, others dispute this.

For example, the distinguished academic, Professor Dianne McGuiness, has claimed research shows children learn more quickly when they are taught phonemic awareness in the context of print rather than in isolation.

And the prominent researcher Professor Mark Seidenberg has made a similar statement on the subject.

Researchers Rhona Johnston and Joyce Watson conducted a study in Scotland to investigate the benefits of teaching phonemic awareness without letters vs a synthetic phonics approach using letters. They found that using letters was more effective.

Wood, C and Connelly V (2009) Chapter 13, Contemporary Perspectives on Reading and Spelling, Routledge

When different sources give contradictory advice, it can be difficult to decide which approach might be the best option.

A good way forward is to see if there have been any reviews or meta-analyses done on the research. These methods analyse and evaluate the results from numerous studies, so their findings are likely to be more reliable than isolated studies or the opinions of individual educators…

The directors of the International Reading Association reviewed the research on teaching phonemic awareness and reading and delivered a position statement on the subject. They concluded…

“… interaction with print combined with explicit attention to sound structure in spoken words is the best vehicle toward growth.”

The US National Reading Panel also conducted a thorough investigation into the teaching of phonemic awareness. Their meta-analysis reviewed over 50 studies on phonemic awareness.

In their report, the researchers made some very clear observations and recommendations about the most effective way to teach phonemic awareness. For example, they stated:

“Instruction that taught phoneme manipulation with letters helped normally developing readers and at-risk readers acquire PA better than PA instruction without letters.”

They also found that teaching phonemic awareness with letters has a more positive effect on subsequent reading skills than teaching it without letters. The same was true for spelling…

“Teaching children to manipulate phonemes with letters exerted a much larger impact on spelling than teaching children without letters.”

(Chapter 2 page 4)

In fact, the effect size (a measure of the size of the improvement) using letters was almost twice as large as the effect size without letters. This was true for both reading and spelling.

(Chapter 2, page 21,22)

The authors of the report went on to say that it’s essential to teach phonemic awareness using letters because this helps children to see the connection between phonemic awareness and its application to reading and spelling.

“Teaching with letters is important because this helps children apply their PA skills to reading and writing.”

(Chapter 2, page 6)

These findings suggest that if children are taught phonemic awareness without letters, they will find it more difficult to transfer their knowledge of phonemes to reading and spelling.

This makes sense because the whole point of teaching phonemic awareness is to help children understand our alphabetic writing system. If they aren’t shown the connection between phonemes and printed words from the start, they might well wonder why their teacher seems to be speaking like a robot!

And the advantage of using letters is also consistent with the theories of multisensory learning and dual coding. Having a visual cue alongside an auditory one is thought to help us process information more easily.

There’s also evidence that getting students to write out letters and words can help them learn more quickly because this helps them to process the information kinaesthetically.

See ‘Is Handwriting Still Important?’ in our article about handwriting.

Other more recent studies agree that it’s not necessary to teach phonemic awareness as an isolated skill before introducing letters. For example, a 2016 study concluded:

“Our results appear to indicate that learning letters does not require previous PA ability…”

Suortti, O. and Lipponen, L. Phonological awareness and emerging reading skills of two- to five-year-old children. Journal of Early Child Development and Care. Volume 186, 2016 – Issue 11 (Feb. 2016).

A 2009 study investigated whether prior training in phonemic awareness without letters helped children learn letter-sound correspondences. It didn’t…

“Overall, the data suggest that there is little value in training pre-schoolers in either letter forms or sounds in isolation in advance of providing instruction on the links between the two.”

And a 2014 meta-analysis that looked at the effectiveness of interventions for people with reading disabilities concluded that stand-alone phonemic awareness training had no significant benefit. It was only beneficial when taught alongside instruction on letter-sound correspondences and decoding (i.e. phonics instruction).

Galuschka, K., Ise, E., Krick, K., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2014). Effectiveness of treatment approaches for children and adolescents with reading disabilities: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

None of this means that verbal phonemic awareness activities should be avoided altogether. For example, children could still practise segmenting simple words verbally at random times when there are no letters available for them to manipulate.

For instance, if one of our daughters noticed a dog or a cat, or some other random thing when we were out, we would sometimes ask them to spell (segment) it using letter sounds (phonemes).

Or we might say something like, “would you like to go on the ‘s’-‘w’-‘i’-‘ng’?” and let them figure out what we meant.

You can do similar informal activities at the dinner table.

And children can get some enjoyment and benefit from listening to adults playing with the sounds in words. For example, using spoonerisms like “he was a very dilly sog” instead of ‘silly dog’.

Drawing a child’s attention to examples of alliteration in names or sentences could also be beneficial for their future writing skills.

However, some types of verbal phonemic awareness activities can actually be more difficult for children to master than reading print. For example, young children can find substituting, adding or deleting individual sounds in spoken words very difficult.

This is hardly surprising because these tasks not only require a high level of phonemic awareness, they also make significant demands on children’s working memories. And as young children have smaller working memory capacities than adults* such tasks can put a significant cognitive load on little minds.

Gathercole, S and Galloway, T, (2007) Understanding working memory a classroom guide.

Experiments have shown that children do much better on phoneme manipulation tasks when they can see written words compared to doing the same tasks as exclusively auditory exercises.

In one study, a group of children had an 8% success rate in an oral phonemic test but achieved a 57% success rate in a similar test that included written words.

Silva, C. & Alves Martins, M (2010) Relations Between Children’s Invented Spelling and the Development of Phonological Awareness, Educational Psychology 23(1):3-16 · July 2010

So, rather than expecting kids to hold and manipulate all of this information in their heads, it’s much easier for them if they can see and manipulate letters as we describe in our article on spelling with phonics.

Should We Use Letter Names or Sounds When Teaching Phonemic Awareness?

There is little benefit in referring to letter names when teaching phonemic awareness because they don’t correspond to the sounds (phonemes) in words. In fact, using letter names might actually confuse some children and hold back their progress in spelling.

Teaching phonemic awareness with letters should involve the use of the common letter-sound correspondences rather than the letter names. We discuss this issue in more detail in our article about letter names.

What Are the Most Important Phonemic Awareness Skills to Teach?

The National Reading Panel analysis looked into whether it’s better to teach students a wide range of phonemic awareness skills compared to just focussing on one or two skills.

They found that focussing on one or two skills was more effective and they said that blending and segmenting were particularly important skills to master.

“Blending and segmenting instruction showed a much larger effect size on reading than multiple-skill instruction did.”

(Chapter 2, page 29)

This makes sense because blending and segmenting are the two skills most relevant to reading and spelling. The National Reading Panel stressed this point…

“Teaching children to blend phonemes with letters helps them decode. Teaching children phonemic segmentation with letters helps them spell.”

(Chapter 2, page 6)

What Order Should You Teach Phonemic Awareness Skills?

As we discussed earlier in this article, it’s more effective to teach phonemic awareness using letters, so it makes sense to teach the letter-sound correspondences before starting phonemic awareness training. You don’t need to teach the letter names at this stage.

Blending, followed by segmenting, can be introduced once children can say the letter sounds reasonably quickly and accurately.

There’s some evidence that children find blending easier than segmenting*, so it probably makes sense to start instruction with blending exercises first.

*See Hempenstall, K (2014) Phonemic Awareness: Yea, nay?

However, it’s important to introduce segmenting once children have developed a basic grasp of blending.

These two skills are closely related (segmenting is like blending in reverse) and so working on one skill can help to reinforce the other.

As we mentioned above, it’s better to focus on blending and segmenting skills rather than trying to cover a wide variety of phonemic awareness skills.

Young children can find substituting, adding or deleting individual sounds in spoken words very difficult and trying to do too much of this as a verbal activity could be counterproductive.

But manipulating magnetic letters or alphabet cards can become integrated into blending and segmenting sessions as we describe in our article on spelling with phonics.

Help With Speech Sounds

Some children can have problems distinguishing between similar sounds. For example, the sound represented by the letter combination ‘th’ in the word ‘thin’ is only slightly different from the sound represented by ‘th’ in the word ‘this’.

One solution recommended by some educators is to do activities that can help children become more aware of their mouth and lip movements and the contribution of their voice boxes for different sounds.

You can see Denise Eide of The Logic of English site explain the idea in this video:

The Lindamood Phoneme Sequencing® Program for Reading, Spelling, and Speech, also known as the LIPS programme, uses the same idea.

A meta-analysis that looked into its effectiveness found there was only limited evidence that the programme could be effective and said that more research was needed. Nevertheless, the authors of the study cautiously recommended the programme.

Malani, M. et al. (2011) The LIPS program for Language Intervention: A Meta-Analysis

After watching a video demonstrating the LIPS programme (shown below), our own feeling is that the process seems to be a bit protracted. However, it’s probably worth trying some of the activities with an individual child who might be struggling with a particular speech sound.

Resources

There are a variety of printable and online phonemic awareness resources that you can access from our Free Phonics and Phonological Awareness resources section.

We also recommend a variety of activities that can be done at home or in a school setting in our article, ‘Phonological/Phonemic Awareness Activities for Parents and Teachers’.