Do children really need formal reading instruction? Some people say they don’t. Read our assessment of this claim.

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Contents:

- Introduction

- Learning to Read Is Different From Learning to Speak

- No One Learns to Read Completely Independently, Children Need Guidance Even When They Are Learning a Spoken Language

- Some Children Might Not Be Able to Learn to Read Independently…

- Direct Instruction Seems to Be More Efficient Than Discovery Learning

- Children Could Miss a Lot of Educational Opportunities if They Are Left to Learn Independently

- Conclusion

- Further Information

- References

Summary…

- Some children can pick up reading without formal instruction, but they still need some kind of adult interaction in the same way that children need adult interaction when they are learning to talk.

- Although there are some similarities between reading and understanding spoken language, there are also some key differences between verbal and written communication.

- There is strong evidence that some children struggle to pick up reading skills without clear, direct and detailed instruction, so withholding reading instruction could delay the progress of a number of children.

Introduction

People who recommend this approach believe that learning to read can be a natural process, much like learning to understand a spoken language.

Some claim that children don’t need any guidance as long as they grow up surrounded by people who read.1

Others, such as Timothy Kailing, author of the book ‘Native Reading’, suggest that running your finger under the text as you read to your child might be sufficient, as long as you start this when they are between one and three years old.2

The idea of children learning to read independently seems to be popular within some home-schooling groups and with parents who send their children to schools with more individualised and explorative learning philosophies:

“The little learning machines who learn to walk by walking and talk by talking also learn to read by reading and write by writing.” 3

Stories about children who’ve learned to read without much help suggest that it is possible (given the right circumstances).1 However, we think you should be cautious about adopting this approach for a number of reasons…

Learning to Read Is Different From Learning to Speak…

It’s true that writing and speaking do have things in common – they’re both ways of expressing language and communicating information. However, there are some key differences between verbal and written communication:

- Humans have been speaking and listening to each other since long before the first major civilisations emerged thousands of years ago. In comparison, the expectation that ordinary people should be able to read and write has only been around for a very short time – no more than a few hundred years in most countries.

So, for most of human history, the vast majority of people have been illiterate. This means that reading hasn’t been a natural part of our social development in the same way that spoken language has.

- Almost all youngsters learn to understand and speak a language quite well without any special instruction, as long as they are exposed to words from an early age. In contrast, many people struggle with literacy skills all of their lives. For example, in the USA around one-quarter to one-third of children don’t even reach the most basic levels of literacy when they leave school.4

It seems that learning to read is more difficult for a lot of people than picking up a spoken language. We explore some of the reasons for this in our article “Why Learning to Read Is Difficult”.

- Humans have been speaking and listening to each other since long before the first major civilisations emerged thousands of years ago. In comparison, the expectation that ordinary people should be able to read and write has only been around for a very short time – no more than a few hundred years in most countries.

A number of prominent academics have questioned the idea that reading is natural…

Keith Stanovich, Professor of Applied Psychology at Toronto University, has written:

“the idea that learning to read is just like learning to speak is accepted by no responsible linguist, psychologist, or cognitive scientist in the research community.” 5

And in his forward to the book, “Why Our Children Can’t Read”, well-known cognitive neuroscientist Steven Pinker wrote:

“Language is a human instinct, but written language is not… Children are wired for sound, but print is an optional accessory that must be painstakingly bolted on.” 6

No One Learns to Read Completely Independently, Children Need Guidance Even When They Are Learning a Spoken Language…

We know that learning to talk comes naturally to most children because relatively few kids ever need help from speech and language professionals. However, most kids actually get a lot of help from their parents when they are learning to talk.

Professor Pamela Snow, a respected psychologist and speech pathologist, has pointed out:

“…children’s acquisition of oral language, while strongly “pre-programmed” in an evolutionary sense, still requires enormous environmental input and interaction, in the form of exposure, simplification, repetition, imitation, expansions, recasts, and so on”. 7

Parents don’t just engage in conversation with other adults and expect their children to pick up the language while they play in the corner of the room. They help their children to develop phonological awareness and understand verbal communication.

In essence, they actually teach their children how to speak and understand language, although they do much of this intuitively through baby talk and other interactions. For example:

- When our children are babies we instinctively speak to them using short, simple words and phrases and we exaggerate or emphasise some of the sounds and movements of our mouths.

- Once children start to say a few words we give them positive feedback by smiling and sounding excited.

- We help them to refine their pronunciation by repeating the words they say.

- We point to objects and pictures and say what they are.

- We read to them and do nursery rhymes to help them get a feeling for the rhythm of the language.

- We might provide a running commentary on the actions and behaviours of our children: “Johnny’s clapping,” “what a nice smile”, etc.

- As their vocabulary increases, we gradually speak to children using longer phrases and sentences and introduce them to words connected to more abstract ideas.

“Oral language, then, is one of those deceptively complex processes that by virtue of its pervasive presence in our lives can appear simple, or even inconsequential, as a developmental achievement. It is neither.” 7

So learning to talk requires a lot more support and feedback from adults than many people realise, and so does learning to read.

You could leave a bunch of young children alone in a library for several hours every day until they were teenagers, but it’s extremely unlikely that any of them would learn to read without adult interaction.

Even people who promote the idea of children teaching themselves to read recognise that it doesn’t happen in isolation:

“Reading, like many other skills, is learned socially through shared participation.” 1

Often, when people say their child learned to read independently they are referring to the fact that the child was self-motivated to read and took responsibility for their own learning. But that doesn’t mean they were just left on their own without any support.

At the very least, kids need to see written words and hear them being spoken at the same time, so they can begin to understand the correlations between written and spoken language.

So, as an absolute minimum, children should be read to by supportive adults, and this needs to happen often. But even this might not be sufficient for most children to develop into fluent readers.

Some Children Might Not Be Able to Learn to Read Independently…

The proportion of children who might be capable of learning to read on their own is unclear because we aren’t aware of any reliable studies that have investigated this.

There are some well-documented success stories, but people are more likely to report successes than failures. Few people would admit that their child is a poor reader because they didn’t allow them access to any reading instruction.

In the absence of any reliable data, we think it could be quite a risk see if your child can learn to read on their own. The proportion of children who might struggle could be quite high given that many kids find reading difficult even when they do get instruction at school.

And the chances that a child will catch up get lower the longer a struggling reader is left before an intervention. 8

Direct Instruction Seems to Be More Efficient Than Discovery Learning…

Children learn faster when they are given clear instructions about how to do something, and their understanding is just as good as the understanding of children who learn by figuring things out by themselves.

This has been demonstrated in controlled experiments where some students work out problems for themselves while others are told explicitly how to do the same problems using teacher explanations and worked examples.

A review of this research concluded:

“Decades of research clearly demonstrate that for novices, direct, explicit instruction is more effective and more efficient than partial guidance.” 9

The review also stated that the case for direct instruction of new material is also supported by current theories of how we learn from the field of cognitive psychology.

Studies looking into how children learn to read have also shown that they learn quicker when they get more direct instruction. For example, Jim Rose, who was commissioned by the UK government to do an extensive review of the teaching of reading, concluded:

“It is therefore crucial to teach phonic work systematically, regularly and explicitly… It cannot be left to chance, or for children to ferret out, on their own, how the alphabetic code works”. 10

See our article, ‘Is Phonics the Best Way to Teach a Child to Read?’ for more examples of studies on reading instruction.

This doesn’t mean that children can’t learn things independently. It’s widely known that children who read frequently with adults (or independently) can learn how to read words they haven’t been taught. Unplanned learning that’s acquired as a by-product of engaging in another activity is sometimes described as incidental learning.

And the renowned academic, Professor Mark Seidenberg, says children accomplish this through a process he describes as ‘statistical learning, which takes place without conscious awareness or intention.

However, research has shown that prior knowledge has a significant influence on incidental learning*, and Seidenberg has found that well-timed and targeted instruction accelerates statistical learning#.

*WILLIAM D. WATIENMAKER, W. (1999) The influence of prior knowledge in intentional versus incidental concept learning, Memory & Cognition 1999, 27 (4), 685-698

#Seidenberg, Mark. Language at the Speed of Sight: How We Read, Why So Many Can’t, and What Can Be Done About It (p. 87). Basic Books. Kindle Edition.

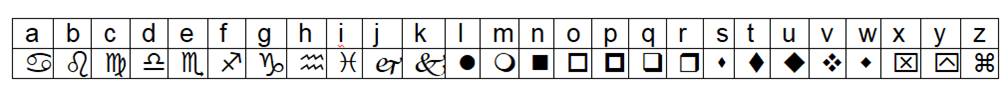

To illustrate why explicit instruction is helpful, try to work out what the message below says. You might be able to figure it out yourself, but most people will find it’s quicker when the code has been explained to them.

it is quicker when it has been explained to you

The same is true for children trying to learn the English alphabetic code.

There’s a table that explains the code we used above at the end of this page if you want to read the message.

Children Could Miss a Lot of Educational Opportunities if They Are Left to Learn Independently…

Reports about children who’ve learned to read independently suggest that many of them master reading much later than children who are taught in traditional schools. 1

Apparently, some independent readers don’t learn until they are in their early teens.

This doesn’t create a huge problem for home-schooled children, or for those who attend schools with more individualised learning philosophies. Such children will usually have someone on hand to read or explain things to them.

However, they will miss out on the pleasure of absorbing themselves in a book during independent reading.

And children who don’t have someone willing and available to read to them on demand could miss out on a lot of learning opportunities.

“Once a child has learned to read they can read to learn”.

The above statement is used a lot in education and it’s very true. Of course, there are ways to educate children that don’t depend on their reading skills, but once they can read fluently their learning opportunities can increase enormously.

Some people worry about directing their child’s learning; they think that giving them reading instruction before they ask for it is reducing their freedom to choose.

There is some truth in this, but it could be argued that making choices for your child is part of the responsibility of being a parent.

We guide our kids indirectly by the environment we allow them to grow up in, by the examples we set and the things we make available to them. With complete freedom, some kids might choose to watch TV and play computer games all day.

Once a child can read, they will have much more independence and freedom to choose how and what they want to learn.

Another worry is that forcing a child to engage in lengthy drilling could put them off reading, and we think this is a reasonable concern. But reading can be taught in bite-sized chunks using a variety of activities that children enjoy.

And once children recognise their own progress they often become self-motivated. As the respected educationalist Michael Marland once said, “being able to do is very close to wanting to do.”

Conclusion

We think that everyone has the right to educate their child in a way that feels comfortable to them. But learning to read is not a natural part of child development and it’s much too important to leave it to chance.

The idea that children should be able to learn to read without instruction is comparable to the idea that they should learn to drive or play the piano without lessons.

While this might be possible for some, even those with a natural aptitude would almost certainly learn faster and more efficiently with proper instruction.

Solution for Coded Message:

it is quicker when it has been explained to you

The message says: it is quicker when it has been explained to you

See below for information on the best ways to teach a child to read, write and spell.

Further Information…

Click on the following link you would like to learn more about teaching your child to read using phonics.

If you want to know how to improve your child’s reading comprehension, see the following article: Reading Comprehension Basics.

Click on the following link if you would like to know more about teaching spelling with phonics.

We also have an article about teaching your child to write.

References:

- Peter Gray Ph.D. Freedom to Learn Blog, Children Teach Themselves to Read

- Kailing, T. The Native Reading Website (2008).

- Linda Dobson, homeschooling advocate: https://www.techlearning.com/tl-advisor-blog/3693

- For example the 2011 report from the U.S. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

- Stanovich, Keith E. Progress in Understanding Reading, 415. New York: The Guilford Press, 2000.

- McGuinness, D. (1999), Why Our Children Can’t Read And What We Can Do About It, Scribner.

- If learning to read is a “linguistic task”, what’s wrong with Whole Language?: http://pamelasnow.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/if-learning-to-read-is-linguistic-task.html

- Elliot, J. Grigorenko, E. (2014), The Dyslexia Debate, Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, R. Kirschner, P. Sweller, J. (2012), ‘Putting Students on the Path to Learning, The Case for Fully Guided Instruction’, American Educator, Spring 2012

- The Independent review of the teaching of early reading (Rose Report 2006) p18-19