Definition, examples of phonological awareness skills, teaching strategies and activities, assessments and more…

Introduction

Phonological awareness is considered to be a key early literacy skill and it’s frequently mentioned in discussions about dyslexia or struggling readers.

However, many parents and educators aren’t clear about the precise meaning of the term, and it’s often confused with phonics or other reading terminology.

In this article, we describe what phonological awareness means in plain English, and we explain why it’s important.

We also give examples of phonological awareness skills, teaching strategies, assessments and answer many more common questions about phonological awareness.

Use the links in the table of contents below to navigate through the article…

Contents:

- What is Phonological Awareness?

- Examples of Phonological Awareness Skills

- Importance of Phonological Awareness

- When Should You Teach Phonological/Phonemic Awareness?

- How to Teach Phonological Awareness

- Phonological Awareness Assessment

- How to Help Students Who Struggle with Phonemic Awareness

- Other Common Questions about Phonological Awareness.

What is Phonological Awareness?

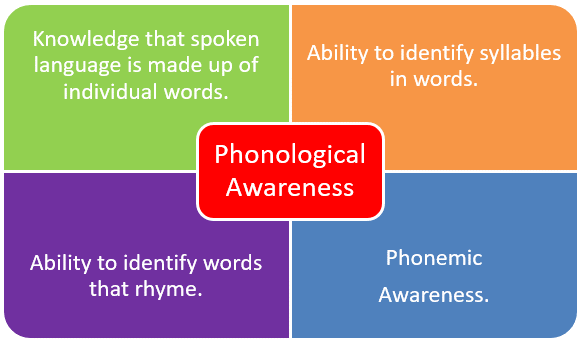

A concise definition of phonological awareness would be the ability to recognise, understand and manipulate the different types of sounds in spoken language.

However, is difficult to explain phonological awareness fully in a single sentence because it involves a range of skills and abilities. A more thorough explanation would include:

- The ability to recognise that spoken language is made up of sounds that can be broken apart into different sized ‘chunks’. For example, sentences can be separated into individual words, and words can be broken up into syllables and phonemes.

- The ability to identify similarities and differences in the various types of spoken sounds. For example, recognising words that rhyme and identifying ones that don’t, and being able to tell if words start or end with the same sound.

- The ability to recognise that spoken language is made up of sounds that can be broken apart into different sized ‘chunks’. For example, sentences can be separated into individual words, and words can be broken up into syllables and phonemes.

The term ‘phonological’ is based on the Ancient Greek word ‘Phono’ which means sound or voice. This indicates that phonological awareness is an auditory skill, not a visual one.

It involves listening to and processing the sounds in spoken language and although it plays an important role in reading, it can be practised without looking at written text.

Examples of Phonological Awareness Skills

A child with good phonological awareness should be able to:

- Understand that sentences are made up of individual words.

- Identify syllables in words.

- Recognise the onsets and rimes in syllables.

- Recognise words that rhyme.

- Recognise and manipulate the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words.

The last skill in the above list is known as phonemic awareness and this is a fairly broad concept in its own right. We’ve produced a separate article on phonemic awareness if you want to learn more about it.

Importance of Phonological Awareness

Research suggests that phonological awareness plays a significant role when children are learning to read and spell words.

Some academics have argued that a causal link between phonological awareness and reading ability hasn’t been fully proven.* Nevertheless, there are sufficient grounds for believing there could be one.

*See, for example, Hempenstall, K. (2014), Phonemic Awareness: Yea, nay?

Professor Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive neuroscientist who has studied language, reading and dyslexia for over 30 years has written:

“… the evidence that the phonological pathway is used in reading and especially important in beginning reading is about as close to conclusive as research on complex human behaviour can get.”

Seidenberg, M. (2017), Language at the Speed of Sight – How We Read, Why So Many Can’t and What Can Be Done About It, Basic Books.

Another leading researcher of language, the cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene, agrees with Professor Seidenberg. In his book, Reading in the Brain, he wrote:

“There is abundant proof that we automatically access speech sounds while we read.”

Dehaene, S. (2009) Reading in the Brain, Penguin Books

This is why phonological awareness skills are included in the Kindergarten foundational skills for reading in the USA Common Core State Standards Initiative.

And phonological awareness activities are also specifically mentioned in Phase 1 of the UK Government’s Letters and Sounds document. This provides guidance for Literacy instruction in the Early years foundation stage of the UK National Curriculum.

How Does Phonological Awareness Affect Reading?

The English writing system is based on an alphabetic code, which means there is a connection between the printed letters in written words and the sounds in spoken words.

Consequently, if children don’t have an awareness of the sounds that make up words (phonological awareness), they are likely to find reading more difficult.

In fact, if young children show a lack of phonological awareness in simple tests, this is one of the strongest predictors that they will struggle with reading in school.*

* Moats, L and Tolman, C. Why Phonological Awareness Is Important for Reading and Spelling.

And some of these children may ultimately be diagnosed as dyslexics. Professor Dehaene has written:

“… a core deficit in phonological processing lies at the origin of most dyslexia.”

Dehaene, S. (2009) Reading in the Brain, Penguin Books

See our article on dyslexia for more information on this subject.

Phonological Awareness and Spelling

Phonemic awareness, which is a sub-skill of phonological awareness, is especially important for spelling. Children need to be able to segment spoken words into their constituent sounds to become proficient at spelling, and this requires good phonemic awareness.

We discuss this in more detail in our phonemic awareness article.

When Should You Teach Phonological/Phonemic Awareness?

You can start laying the foundations for phonological awareness from the day your child is born. Just engaging in normal ‘baby talk’ with your infant can help them become sensitive to the sounds used in their language.

And you can also sing and do nursery rhymes with your child from a very young age.

Phonological Awareness for Toddlers

As your children grow from babies to toddlers, everyday conversations and regular reading time will continue to develop their future phonological skills; however, there are other activities you can do to help them along the way…

For example, clapping along to songs such as Pat-a-Cake can be done with babies and toddlers and this can help children grasp the natural rhythm of the language, as well as helping them identify individual words in sentences.

You can also clap out the syllables in words for your child once they can say words clearly and have developed a reasonable vocabulary. It might take some time before they can clap out the syllables in words for themselves, but they will get there more quickly if you start when they are young and repeat the activities every week or so.

See our article, ‘Phonological/Phonemic Awareness Activities for Parents and Teachers’ for more ideas.

Some people give up too soon with activities if it seems like their child isn’t making any progress. However, children can be making new neural connections every time they observe and listen to an activity, even when they are showing no visible signs of learning.

Small changes in the brain can accumulate over time until, eventually, a child is able to demonstrate that they’ve grasped an idea. This might seem like a sudden breakthrough, but it can actually be the culmination of a gradual increase in understanding.

Although many children can’t identify rhymes or the individual sounds in words (phonemes) until they’re around 5, it is possible for some children to learn to do these things at a much younger age.

We taught our own children the common sounds represented by each letter of the alphabet before they were 18 months old, and they were able to blend letters and sounds to identify simple words before they were two.

One study found that preschool children were able to learn letter-sound correspondences even when they had no measurable level of phonemic awareness.*

You don’t have to start teaching your child these things at such a young age, but if you want to you don’t have to worry about it being ‘developmentally inappropriate’.

As we discussed in our section on phonological/phonemic awareness development, there isn’t a fixed sequence that needs to be adhered to because phonemic awareness isn’t a naturally acquired skill. Children only become aware of phonemes if we provide them with activities that draw their attention to phonemes.

We haven’t seen any evidence that learning about phonemes from a young age can do any harm. In fact, we think it benefited our children enormously, as they went on to become fluent readers and very good spellers well before they started school.

See our article ‘should I teach my baby or toddler to read?’ for a more detailed discussion about this issue.

How to Teach Phonological Awareness

Many phonological awareness skills can be taught without formal instruction. Everyday activities like nursery rhymes and singing and clapping games can help to lay the foundations of these early literacy skills.

Using spoonerisms such as ‘runny babbit’ for bunny rabbit can also be a fun way to get kids to pay more attention to the sounds in words.

The use of alliteration is another informal way to draw the attention of kids towards the sounds in words.

See our article, ‘Phonological/Phonemic Awareness Activities for Parents and Teachers’ for information about getting the most out of these activities (which can be done at home or in a classroom environment).

Doing some more structured exercises can also be beneficial, and we’ve included examples of these with links to free resources in the above article.

However, we don’t think it’s necessary to do a lot of structured phonological awareness activities before teaching kids some basic phonics skills.

Some educators go over the top with phonological awareness activities in our opinion.

For example, one curriculum we viewed had over 100 separate exercises, which could take months to work through. And in all of this time, the children aren’t introduced to any letters or written words.

Kids are likely to find phonological awareness activities more interesting and relevant if they are shown how they are related to reading and writing. And in order to do this, they need to be introduced to letters and printed words sooner rather than later.

As researchers from Florida State University stated in a publication about phonological awareness:

“Stimulation of phonological awareness should never be considered an isolated instructional end in itself. It will be most useful as part of the reading curriculum if it is blended seamlessly with instruction and experiences using letter-sound correspondences to read and spell words.”

Torgesen, J.K., & Mathes, P.G. (1998). What every teacher should know about phonological awareness. Florida Department of Education, Division of Public Schools and Community Education.

Some educators don’t realise that phonics instruction in blending and segmenting actually helps to build phonemic awareness more quickly and effectively than activities done without letters.

See our passage, ‘What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?’ for more information on this.

For detailed activities and resources which can be used at home or in a classroom environment, see our article, ‘Phonological/Phonemic Awareness Activities for Parents and Teachers.’

Phonological Awareness Assessment

The Importance of Phonological Awareness Assessments…

Since a lot of research suggests that phonological awareness is important for reading, it makes sense to assess students for it in early education settings.

Assessments for phonological awareness could help teachers identify students at risk of future reading difficulties.

The well-published educational psychologist Dr Kerry Hempenstall says it’s important to assess all students when they start school…

“…assess all students on arrival using a combination of phonemic awareness and letter-sounds/names fluency measures (and possibly include a naming speed task). Assume that those students who struggle with these tasks will require intensive intervention from the beginning.”

Hempenstall, K. (2014), Phonemic Awareness: Yea, nay?

The comment Hempanstall makes about interventions is important. Assessments are pointless if we don’t act on the information they provide.

Students who struggle with these assessments are likely to need extra help if they are going to make satisfactory progress in reading and spelling.

Children with weaknesses in phonological awareness may or may not have learning disabilities.

Some deficiencies that are picked up in tests can be due to developmental disorders, but they can also be a consequence of a child’s early experiences. It can be difficult to tell the difference.

Nevertheless, it’s important to intervene whatever the underlying cause. And for those kids who do need interventions, it’s also important to focus on the skills which are most important for reading.

See ‘How do you help students who struggle with phonemic awareness?’ below in this article.

What Assessment Should be Used?

An assortment of assessments are available and this can make deciding what to use and when to use them a bit overwhelming.

For example, there’s the DIBELS assessment (which stands for Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills), the Kindergarten Readiness Assessment – Literacy (KRA-L), the Yopp-SingerTest of phoneme segmentation and the Phonological Assessment Battery (PHAB).

This article from the LD Online website recommends that teachers use a variety of screening measures and it also provides a comprehensive list (and evaluation) of some widely used phonological awareness assessments.

But to complicate matters further, a number of academics think that some assessments cover more aspects of phonological awareness than is necessary:

“Current phonological awareness tests, it appears, demand more phonological skills than certain aspects of literacy learning do. … we conclude that phonological awareness as currently assessed is not a good measure of the phonological skills that are needed to learn about letters and reading.”

Treiman, R., Pennington, B. F., Shriberg, L. D., & Boada, R. (2008). Which children benefit from letter names in learning letter sounds? Cognition, 106, 1322-1338.

While not all academics are in agreement with the above statement, we believe that some verbal phonemic awareness activities can be more difficult for children than reading print.

In particular, some young children can find substituting, adding or deleting individual sounds in spoken words very difficult.

For more information about the reasons for this, see our discussion under ‘What Are the Most Important Phonemic Awareness Skills to Teach?‘ in our phonemic awareness article.

Also, one study suggested that phoneme awareness is a better predictor of early reading skills than onset-rime awareness, so perhaps it’s not as important to assess for onset-rime skills.

It’s also worth noting that not everyone agrees that it’s important to get kids to pass all of these assessments before they start phonics instruction. In fact, phonics instruction actually helps children develop phonemic awareness skills.*

*See ‘What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?’ in our phonemic awareness article.

So basic phonics skills can be taught alongside phonological awareness training.

Free Phonological Awareness Assessments

There are a variety of free and simple ways that teachers or parents can informally assess the phonological awareness of youngsters.

Although some of these methods might not be quite as sophisticated as commercially available tests, they can still provide you with some useful information about who might need extra support and what skills they need help with…

- Some of the free activities available from our ‘Phonological/Phonemic Awareness Activities for Parents and Teachers’ article could be used as quick and informal assessments.

- There’s a very simple and quick check for phonological awareness on the All About Learning Press site.

- The Right Track Reading site also provides an informal and quick evaluation of phonemic awareness.

- And there’s a fairly comprehensive set of free assessments in the Ultimate Guide to Phonological Awareness document from the Essex Special Educational Needs and Children with Additional Needs Service (SENCAN) in the UK.

- You can also click on the following link to get a free copy of the Rosner Test of Auditory Analysis Skills. This also gives an indication of expected levels for different age groups.

How to Help Students Who Struggle with Phonemic Awareness

Here are 10 suggestions that could make phonemic awareness interventions more effective…

1. Teach phonemic awareness in the context of print.

2. Focus mainly on blending and segmenting activities.

3. Concentrate on phoneme blending.

4. Don’t attempt phoneme addition, deletion or manipulation activities without printed words.

5. Avoid referring to the letters by their names.

6. Blend words that start with continuous sounds first and exaggerate troublesome sounds.

7. Motivate – give praise for effort as well as achievement.

8. Practice in small groups or one-to-one.

9. Practice daily.

10. Use multisensory learning.

1. Teach phonemic awareness in the context of print…

Phonemic awareness doesn’t have to be taught as a stand-alone verbal and auditory exercise before introducing letters.

Although some educators give contrary advice, research suggests that children pick up phonemic awareness more quickly when they can see written words and letters while they are listening to spoken words and sounds.* This is true for normally developing readers and struggling readers.

*See ‘Should Phonemic Awareness be Taught Without Letters?’ in our phonemic awareness article for more information about this.

2. Focus mainly on blending and segmenting activities…

This is likely to give better results than teaching a wide range of phonemic awareness skills. See ‘What Are the Most Important Phonemic Awareness Skills to Teach?’ in our phonemic awareness article for more information on this.

Make sure the children are fluent with the most common letter-sound correspondences first and then start blending exercises using printed words.

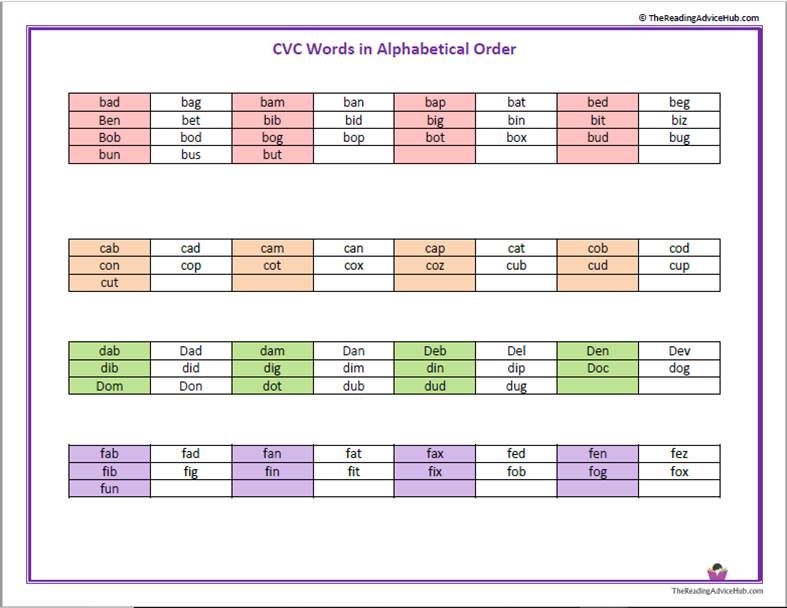

It can really help to have plenty of suitable examples of words to hand when you do a session with a child because it can sometimes be difficult to think up enough suitable words on the spot.

CVC words can make ideal phonemic awareness word lists for struggling readers and we’ve compiled a comprehensive set of CVC word lists that you can download for free from this site.

Introduce segmenting once children have developed a basic grasp of blending. The two processes are reversible, so working on one of these skills can help to reinforce the other.

3. Concentrate on phoneme blending…

Children are sometimes taught how to blend syllables and onsets and rimes alongside instruction on blending phonemes.

While there may be some benefits to exploring larger units of sound, children who are struggling with phonemic awareness might be confused if they are working on several ideas at the same time.

For example, a word like ‘frog’ would be split into two sound components during onset and rime instruction – the initial blend ‘fr’ and the word ending ‘og’.

But the blend ‘fr’ contains two distinct sounds (phonemes) represented by ‘f’ and ‘r’, and the ending ‘og’ is also made of two sounds represented by ‘o’ and ‘g’.

Similarly, the word ‘split’ contains 5 distinct phonemes, but it would be taught as 2 units of sound as onset and rime.

Although this might make perfect sense to an experienced teacher, it could be baffling for a student who is lacking phonemic awareness.

Teaching several ideas at the same time is likely to increase the cognitive load for struggling students.

If they get a more consistent approach focussed on one key idea, they are more likely to understand the concept of phonemes. So teach kids to sound out each letter in blends and word endings individually until they’ve firmly grasped the idea.

Once they’ve ‘got it’, you can move on and explore onset and rimes and word families.

4. Don’t attempt phoneme addition, deletion or manipulation activities without printed words…

Doing these activities as a purely auditory exercise requires children to hold and juggle a lot of information in their heads, and this can really overload their working memories.

Children have more limited working memories than adults and approximately 70% of children with learning difficulties in reading have a poor working memory.* These are likely to be the same children who struggle with phonemic awareness.

*Gathercole, S and Galloway, T, (2007) Understanding working memory a classroom guide.

Using printed words significantly reduces the working memory load for children because they don’t have to hold everything in their heads if they can see the words in front of them.

The printed words provide a form of scaffolding, and this is especially important for struggling children who need extra support to do tasks successfully.

This is comparable to working out written sums using a pen and paper. We find written calculations much easier than doing the same sums in our heads because mental arithmetic makes greater demands on our working memories.

The same is true for written phonemic awareness activities versus purely auditory ones.

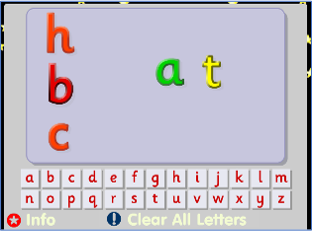

So, rather than Elkonin boxes and counters, use magnetic letters, alphabet cards, whiteboards or software (like the electronic version of magnetic letters below) to demonstrate how words can be constructed and altered by adding or rearranging letters.

It’s important to emphasise the sounds represented by each letter when you do this because the students are still doing an auditory exercise – the letters are just providing some visual support.

Using the letters above as an example, after constructing and sounding out the word ‘at’, show how it can be made into another word by adding the letter ‘b’ as you sound out the word ‘bat’. Then see if the student can figure out how to make the words ‘hat’ and ‘cat’ using the remaining letters.

If they struggle, ask them the sounds for the remaining 2 letters and ask them “which one does ‘hat’ start with?” If they aren’t sure, say the sounds for the 2 letters and ask them again. Then sound out the whole word for them as you construct it with the letters.

The key thing with struggling readers is to do lots of examples. With every new example you do, their brains will make stronger connections and associations – even though you might not see visible signs of progress at first.

After doing a series of examples over a few days, come back to some of the same examples after a week or so to see if the student can now do them independently.

You can also alter the middle and ending letters in words when you are working on phonemic awareness. We discuss how to do this in more detail in our article about spelling with phonics and you can find plenty of suitable examples if you download our free CVC Word lists.

5. Avoid referring to the letters by their names…

When you are working on phonemic awareness with print, it’s important to use the letter sounds exclusively. Avoid referring to the letters by their names because this can be potentially confusing for some children and letter names have very little relevance to phonemic awareness or reading. See our article about letter names for more information on this.

6. Blend words that start with continuous sounds first and exaggerate sounds…

Children can find it easier to blend words containing continuous sounds, so focus on these first. Once your child has shown some progress, move on to words that begin with stop sounds. See our passage on smooth/continuous blending for more information on this.

If a child has trouble hearing the difference between a pair of speech sounds, exaggerate the sounds to increase the contrast between them.

Exaggerating sounds might include ‘stretching out’ continuous sounds, repeating stop sounds several times in close succession, or saying the sounds more loudly.

Once the child can consistently distinguish between the exaggerated sounds, gradually move towards a more normal pronunciation until they can detect the differences between the regular sounds.

7. Gain Attention and Improve Motivation…

Even the best activities and strategies will be ineffective if the struggling students aren’t paying attention or if they’re in a negative frame of mind.

According to the expectancy-value theory of motivation, we won’t fully engage in an activity unless we think we have a chance of doing it successfully.

So, one of the first things you could do to motivate a child is to share examples of previous students you’ve taught. This is because kids and adults are sometimes more convinced by personal stories than by facts and figures.

So rather than saying that 90% of kids with similar problems usually improve, it might be better to talk about ‘little Jenny’ who really struggled at first but now loves books and is doing well at school.

A child’s belief about his or her potential to succeed in a particular subject is sometimes called their ‘academic self-concept’, which is a bit like self-esteem.

And it seems that one of the best ways to improve academic self-concept is to give them the opportunity to succeed at something*.

*Muijs, D. and Reynolds, D. (2011) Effective Teaching: Evidence and Practice, Sage Publications Ltd.

So it’s important to start with relatively simple examples so the struggling student can see some early success. ‘Small wins’ like these are important because they help to instil a belief that improvement is possible.

And seeing some progress early on gives students the confidence to attempt more difficult tasks.

Making learning into a game can also be a good way to engage struggling students. The free online games we’ve compiled are ideal for this.

One other thing…

When you’re working with struggling readers, they’re bound to make mistakes more often than typical readers, so it’s important to be patient and give praise for effort as well as achievement.

There’s some research to suggest that praising effort can help students to develop a Growth Mindset which can improve their motivation and make them more likely to continue trying.

8. Practice in small groups or one-to-one if possible…

Mixed ability teaching can work in some situations, but if you have children who are falling behind the majority of their peers, they will almost certainly benefit from some focused attention on their specific needs.

One-to-one is ideal because children can sometimes distract each other even in small groups. However, we appreciate that some schools don’t have the resources to do this.

9. Practice daily if possible…

You might need to continue working with struggling readers for several weeks or months until they’ve shown some real progress.

According to literacy expert Professor Tim Shanahan, the amount of teaching time is the most important factor in reading instruction. However, it’s better to do frequent short sessions of around 20-30 minutes than to do infrequent longer sessions of an hour or more.

10. Use Multisensory Learning…

The most effective way to employ multisensory learning is to handwrite words while saying them out loud.

Writing is a kinaesthetic activity and neuroscientists believe that spatial and motor learning helps the visual system recognise letters*.

*Dehaene, S. (2019) Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read, Penguin Books.

Studies have shown that children who learn to write letters by hand are better at letter recognition than children who type them on a computer*#.

*The Guardian (Dec. 2014), Handwriting vs typing: is the pen still mightier than the keyboard? Anne Chemin.

#Also see ‘Is Handwriting Still Important?’ in our article about handwriting.

Of course, letter recognition isn’t the same thing as phonemic awareness, but phonemic awareness is only useful if it can be seamlessly integrated into reading and writing.

Other kinaesthetic activities such as sliding tokens or tapping arms and tables may have some benefit because they can help children focus and take note of each sound.

However, they don’t make the important links between sounds and letters which are essential for proficient reading and spelling.

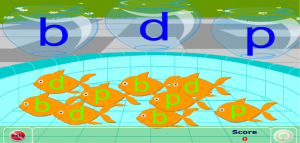

Don’t be too alarmed if a student is prone to reversing letters when they write. This is fairly common with beginning readers.

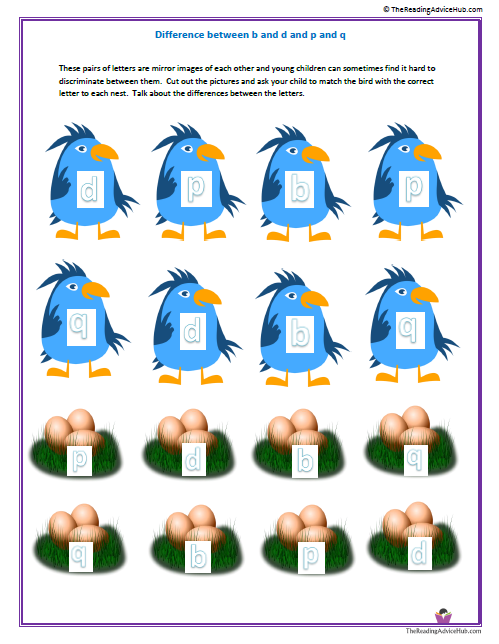

However, it might be useful to compare and do extra practice on the letters which are mirror images of each other – b and d and p and q.

This free Goldfish Game can be helpful for some of these letters:

To access this game, you will need to register with the Literactive site (it’s free). Once you’ve done that, click on the ACTIVITIES tab at the top, then on the Level 1 link in the left-hand margin. You should be able to locate the fishing bowl game along with some other activities.

We’ve produced a similar printable sorting game using birds and nests. Click on this link to download it for free: Difference between b and d and p and q.

However, you should also supplement these activities with plenty of handwriting practice for these letters. You could get your child to do a row of one letter followed by a row of its mirror image.

Other Common Questions About Phonological Awareness

Does phonological awareness include printed letters?

Phonological awareness can be practised and assessed without looking at any printed words or letters because it’s about recognising the sounds in spoken language.

However, a child’s knowledge of phonological awareness can be applied to printed words when they are learning to read and spell. The relationships between the sounds in spoken words and the letters in printed words are emphasised in phonics instruction.

Is Letter Identification Phonemic Awareness?

No, children can be taught to recognise letters and learn their names without having any phonemic awareness skills. Phonemic awareness is an auditory skill, not a visual one.

Nevertheless, a knowledge of letters and their sounds can help children to develop their phonemic awareness. See ‘What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?’ in our phonemic awareness article.

Are Letter Sounds Part of Phonological Awareness?

They can be, but it depends on the context…

Phonological/phonemic awareness involves more than just knowing the sounds represented by letters. It’s about recognising the individual sounds in spoken language.

If you show a child some random individual letters, and they just tell you the sounds represented by each letter, this isn’t a demonstration of phonemic/phonological awareness. That’s because the sounds are not being used in the context of spoken language.

However, if you say the word ‘cat’ and a child can tell you it contains 3 sounds /c/, /a/ and /t/, then they have demonstrated the phonemic/phonological awareness skill of segmenting.

And if a child is able to blend the sounds represented by letters in written words, this is also a phonemic/phonological awareness skill.

What Comes First, Phonological Awareness or Phonics?

Some educators say that children should develop phonological awareness before phonics instruction begins. However, we know from our own experience that children can be taught phonics successfully alongside phonological awareness skills.

Delaying phonics instruction is sometimes based on a belief that phonological awareness develops naturally in a fixed sequence and that interfering with the normal stages of development could be harmful in some way. We’re not aware of any research that supports this claim.

In fact, research has shown that a child’s development is greatly influenced by the input of their teachers and parents. And kids don’t always progress from one skill to another in the same order.

See our article ‘How and When Does Phonological Awareness Develop?’ for a more detailed discussion of these points.

Another common claim is that starting phonics prior to phonological awareness instruction can be confusing for children. But rather than hindering them, early phonics instruction has been shown to help children develop phonemic awareness – the most important phonological skill needed for reading.

What Comes First Phonological or Phonemic Awareness?

Neither, because phonemic awareness is a part of phonological awareness…

The term phonological awareness covers a broad range of language skills, which include things like recognising the syllables in words and identifying words that rhyme as well as noticing the smallest units of sounds in words known as phonemes – phonemic awareness.

See ‘What’s the difference Between Phonemic Awareness and Phonological Awareness?’ in our phonemic awareness article for more information on this topic.

Are Syllables Part of Phonemic Awareness?

No, although the ability to count syllables is a part of phonological awareness.

Phonemic awareness is only about the smallest units of sounds in words which are known as phonemes. Syllables can be made up of larger chunks of sound.

For example, the word ‘windmill’ only contains 2 syllables, but the first syllable is made up of 4 phonemes and the second syllable has 3 phonemes.

Click on the following link to see more detailed examples of phonemes in common words.

Does Phonological Awareness Include Phonemic Awareness?

Yes. Phonemic awareness is a sub-skill of phonological awareness.

See ‘What’s the difference Between Phonemic Awareness and Phonological Awareness?’ in our phonemic awareness article for more information on this.

Does Phonological Awareness Include Phonics?

Phonics is not a part of phonological awareness because phonological awareness involves being able to listen to and identify the different units of sounds in spoken language.

Phonics is more focused on interpreting written language, although it does rely on some phonological awareness skills (phonemic awareness skills).

See ‘What’s the Difference Between Phonics and Phonemic Awareness?’ for more information about this.

Is Decoding Phonemic Awareness?

Technically, decoding isn’t classed as a pure phonemic awareness skill because it involves interpreting printed letters. Phonemic awareness is an auditory skill; it’s about interpreting the sounds in spoken words, not letters in printed words.

However, when children decode whole words from print using phonics, they need to have some phonemic awareness in order to blend the sounds together to identify the words.

Blending is classed as a pure phonemic awareness skill because it can be done with your eyes closed if someone tells you the sounds in the correct sequence.

Is Phonological Awareness the Same as Phonics?

No. But it’s necessary to have the phonological skill of ‘phonemic awareness’ to become proficient at phonics.

See our article, ‘What’s the Difference Between Phonics and Phonemic Awareness?’ for more information about this.

What Is the Connection Between Phonemic Awareness and the Alphabet?

The alphabet is connected to phonemic awareness when the sounds in spoken words are identified and converted into written letters, or when written letters are translated into sounds and then combined to make words (either spoken or ‘in our heads’).

The letters of the alphabet are a symbolic code for the sounds in spoken language. These sounds are known as phonemes and the relationship between spoken sounds and letters is known as the alphabetic code or alphabetic principle.

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify and manipulate phonemes in spoken words, but it can also be applied to written words once the alphabetic code is understood.

The application of phonemic awareness to the letters of the alphabet is at the heart of phonics instruction.

Can Phonemic Awareness be Taught?

Definitely. In fact, a lot of children and adults struggle with phonemic awareness unless they are given explicit instruction.

See our passage, ‘What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?’ for more information.

How Does Phonemic Awareness Relate to Fluency?

Identifying words accurately is an important component of reading fluency and phonemic awareness combined with alphabetic knowledge can help kids with word identification.

In fact, phonics is based on phonemic awareness and knowledge of alphabetic letter-sound correspondences. This approach has been shown to be the most reliable strategy for identifying unfamiliar words in texts.

Without phonemic awareness, children are unable to make the connection between the letters in written words and the sounds in spoken words and this severely limits their ability to identify written words.

Some educators believe that it’s easier to identify unknown words from their context in a sentence. However, research has shown that this isn’t a very reliable method.

In one study, a group of psychology students were given 100 sentences from a popular series of articles and they were asked to predict a single missing word in each sentence. They were only successful around 25% of the time on average*.

*Rayner, K. (1983) Eye Movements in Reading: Perceptual and Language Processes, Academic Press, INC.

And psychology students are likely to have a wider vocabulary and more sophisticated comprehension skills than the average 5-year-old beginning reading instruction.

Of course, there is more to reading fluency than identifying words accurately, but this is a key starting point.

What is the connection between phonemic awareness and invented spelling?

Phonemic awareness is connected to spelling because written English is based on an alphabetic code or principle where letters or groups of letters represent the individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words.

A child with good phonemic awareness is able to segment spoken words into their individual sounds. If they also know the letters that usually represent those sounds they have a good chance of coming up with the correct spelling, or at least a spelling that can be recognized as the intended word.

This is the basic idea behind invented spelling. Children are encouraged to make up their own spellings for words rather than just rote learning them, asking an adult or using a dictionary.

A kid doing invented spelling is essentially using their phonemic awareness and their knowledge of the alphabetic principle to make an educated guess at the correct spelling.

Of course, kids often get their spellings wrong when they start out because many words in English don’t follow the basic alphabetic code and because many sounds can have more than one spelling.

However, phonemic awareness gives them a strategy to work with that can at the very least help them along the way to the correct spelling.

And when children learn about the more advanced aspects of the alphabetic code (for example, the existence of digraphs and trigraphs) their spellings become increasingly accurate.

In fact, studies have indicated that phonemic awareness provides a foundation for the development of spelling.*

*For example, Griffith, P. (1991) PHONEMIC AWARENESS HELPS FIRST GRADERS INVENT SPELLINGS AND THIRD GRADERS REMEMBER CORRECT SPELLINGS, Journal of Reading Behavior 1991, Volume XXIII, No. 2

Morphological knowledge can also help with spelling more advanced words but phonemic awareness can still play an important role in learning new words even when students move beyond reception or kindergarten classes.

Finally, as well as phonemic awareness being important for invented spelling, there’s also evidence that practising invented spelling can help children improve their phonemic awareness.* So the relationship works both ways.

*Silva, C & Alves Martins, M. (2006) The impact of invented spelling on phonemic awareness.