The challenge of deciphering spoken language, how you can help and the stages of phonological awareness…

It Starts in the Womb.

Babies and children develop phonological awareness by listening to speech, and they start acquiring some of these skills before they are even born.

Studies on infants have indicated that babies can detect the rhythms of spoken language several months before they are born. One study on premature babies suggested that babies in the womb might be able to discriminate between different syllables.

Another showed that babies can distinguish between different languages a month before they are born.

Infants continue to develop sensitivity to the changing sounds in words when they listen to spoken language at home or at nursery. However, it can take a while before they are able to discriminate between all the different types of speech sounds…

The Challenge of Identifying Words in Sentences

It might seem obvious to us that sentences are made up of words, but it isn’t to babies who listen to adult conversations. That’s because we often speak very quickly when we’re talking to other adults, and we don’t even pause between every word in a sentence.

Even adults can find it difficult to detect each individual word when they listen to people talking in a foreign language.

This isn’t surprising because there aren’t clear boundaries between words in a spoken sentence. The ends of some words flow into the beginning of words that follow – linking them together.

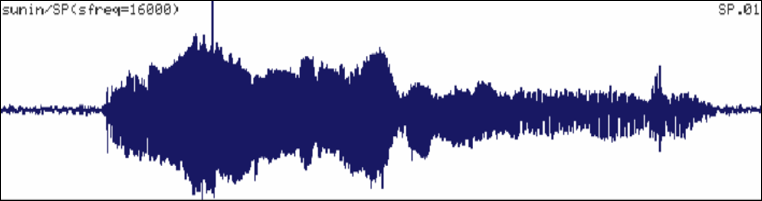

The diagram below shows the waveform from a sentence spoken in the Catalan language (from the north-eastern region of Spain). As you can see, it’s very difficult to be sure where one word ends, and another starts.

And there isn’t much difference when sentences are spoken in English…

Again, there aren’t any clear spaces between each word and it’s not even clear how many words are in the sentence.

Check out the video on Professor Mark Seidenberg’s site to see what the above sentence is and how many words it contains: Where are the “spaces” between spoken words?

Sometimes, we even miss out sounds in words when we link them together, which makes things even harder for infants to learn their language. For example, we might say ‘dunno’ instead of don’t know or ‘wanna’ instead of want to.

Teachers who instruct advanced linguists to speak fluently are aware of these patterns in native languages. They teach their students about the intricacies of what they call ‘connected speech’.

However, babies don’t have the benefit of specialist language teachers. They must decipher the structure of sentences just by listening to the adults they meet. This isn’t an easy task. An author of a study on infant speech commented:

“The challenge faced by infants is comparable to the task faced by adults attempting to identify words spoken in a foreign language.”

Thiessen, E and Erickson, L (2013). Discovering words in fluent speech: the contribution of two kinds of statistical information.

Nevertheless, despite these obstacles, most children do learn to identify individual words in sentences long before they take their first steps.

“…as early as 6 months of age, infants can already exploit highly familiar words-including, but not limited to, their own names-to segment and recognize adjoining, previously unfamiliar words from fluent speech.”

Bortfeld H et al (2005), Mommy and me: familiar names help launch babies into speech-stream segmentation.

How do they manage this?…

The Importance of Baby Talk

It seems that infants benefit greatly from the special way that adults talk to them. Researchers call this ‘infant-directed speech’ or ‘child-directed speech’, but it’s more commonly described as ‘baby talk’.

We instinctively talk to babies in a manner that’s quite different from the way we communicate with other adults. For example:

- We use a higher pitch.

- We exaggerate the movement of our mouths.

- Our facial expressions convey more emotion.

- We talk more slowly.

- We pronounce individual words more clearly.

- We use longer pauses between some words.

- We use shorter words and sentences.

- We simplify our grammar.

- We repeat the same words and phrases more often.

- We exaggerate and ‘stretch-out’ the pronunciation of vowels.

- We emphasise our intonation, so we speak in a more rhythmic or ‘sing-song’ way.

Some parents worry that baby talk could harm their child’s linguistic development. The concern is that listening to a ‘dumbed-down’ version of the language might prevent their child from talking ‘correctly’ when they grow up.

However, such fears aren’t supported by scientific research.

Studies show that talking this way helps to grab a child’s attention and it has other important benefits, such as helping infants recognise different speech sounds.

Baby talk plays an important role in helping children to distinguish between different words in sentences.

See Singh, L et al. (2009) Influences of Infant-Directed Speech on Early Word Recognition.and Thiessen, E et al. (2005) Infant-Directed Speech Facilitates Word Segmentation.

For a more detailed discussion about baby talk, see Dr Gwen Dewar’s excellent article, ‘Baby talk 101: How infant-directed speech helps babies learn language.’

Although kids learn faster from baby talk, they can still pick up a lot of linguistic information by listening to adults speaking normally to each other.

Adult conversations are more difficult to decipher, but young children’s brains are remarkably efficient at noticing the subtle changes in our intonation, tone, stress, and rhythm when we speak. They also learn from statistical patterns in spoken sounds.

Thiessen, E and Erickson, L (2013). Discovering words in fluent speech: the contribution of two kinds of statistical information.

Researchers believe that infants ‘tune in’ to the patterns of stressed syllables in speech and this helps them pick up the rhythm of the language. It’s thought that sensitivity to speech rhythm may be important for the development of phonological awareness.

Wood, C and Connelly V (2009) Chapter 1, Contemporary Perspectives on Reading and Spelling, Routledge

As they get older, babies try to imitate the sounds they hear by babbling to their parents. And if parents repeat the sounds back to them, this helps children refine their speech and their awareness of sounds.

The first clear sign that children can recognise different sounds in words is when they show an understanding of spoken language.

For example, if your child knows that the word ‘hat’ is different from ‘cat’ then this shows they have a rudimentary awareness that the words start with different sounds.

However, most young children aren’t consciously aware of the subtle variations in the sounds in words; their brains identify the differences automatically.

What are the stages of phonological awareness?

Some educators believe that phonological/phonemic awareness develops in a predictable and sequential way – from very basic skills, such as being able to identify the number of words in a sentence, to more advanced skills like being able to segment words into individual phonemes.

Louisa Moats and Carol Tolman have outlined a sequential list of phonological skills and the ages when most children acquire them. You can access these from the following link: ‘The Development of Phonological Skills’.

However, other researchers have shown that there is considerable variation in the age that children develop the different phonological skills, and they don’t all progress from one skill to another in the same order:

“Therefore, to conclude, the outcome of our study suggests that it is no longer helpful to characterise phonological development in terms of a fixed sequence…”

Duncan et al. (2013) Phonological development in relation to native language and literacy: Variations on a theme in six alphabetic orthographies.

Studies also indicate that phonological awareness in children is greatly influenced by the input of their teachers and parents. Kids become more aware of the sounds in words if they do activities that draw their attention to the structure of the language.

So, if parents or teachers do a lot of activities involving rhyming words or clapping out syllables, children are likely to pick up these ideas earlier.

The vocabulary of children is also greatly affected by parental input. And there’s evidence that phonological awareness in children grows as their vocabulary grows. This is especially true during the rapid period of vocabulary growth that begins when toddlers are around 18 months old.

Seidenberg, M. (2017), Language at the Speed of Sight, Basic Books.

As they learn a greater number of new words, youngsters begin to recognise patterns and notice that some of these words contain similar sounds.

Phonemes and Language Development

Professor Mark Seidenberg, a leading researcher of language and reading, has pointed out that we don’t need to have any conscious knowledge of phonemes to use spoken language.

Seidenberg, M. (2017), Language at the Speed of Sight, Basic Books.

This shouldn’t be too surprising because phonemic awareness isn’t a ‘natural’ skill.

Most children only become aware of the smallest units of sound in words (phonemes) when they are given direct phonemic awareness training or reading instruction.

Studies involving adults who have never had the opportunity to learn to read show they have very poor phonemic awareness.

In fact, phonemes don’t really exist as separate units of sound in spoken language at all. The sounds in individual words are actually blended together without any gaps between them.

We discuss this point in more detail in our article about phonemes.

The idea of phonemes is really a consequence of the way we represent language with our alphabetic writing system.

This has been demonstrated in experiments in China…

When children are taught to read in China, they learn traditional Chinese characters, but they are also taught another system called ‘Pinyin’. This is based on the same Latin alphabet that we use in English, as explained in the video below:

Chinese youngsters who’ve been taught Pinyin can demonstrate good phonemic awareness in tests. Yet, Chinese adults who haven’t been taught Pinyin struggle when they are tested for phonemic awareness.

Dehaene, S. (2009) Reading in the Brain, Penguin Books

It has also been well documented that there is some variation in how sensitive individual children are to different spoken sounds.

Unfortunately, some children find it harder to discriminate between sounds and these children are statistically more likely to have reading difficulties when they are older.

We discuss this in more detail in our article about dyslexia.

In fact, research suggests that more than 25% of children will have trouble developing phonemic awareness if they aren’t given explicit instruction about it when they are learning to read.

Jager, M. et al. The Elusive Phoneme, American Educator, Spring/Summer 1998.

Fortunately, phonemic awareness can be taught and there’s evidence that the right type of instruction can improve the reading and spelling of all children, including those who might start out with a natural weakness in this area.

For more information about this, see ‘What’s the best way to teach phonemic awareness?’ in our main phonemic awareness article.