Are sight words really as important as some people claim? Could rote learning sight words actually be a waste of time? Is there a more effective approach?

Numerous articles on the internet stress the importance of teaching sight words to beginning readers.

But what are sight words and are they really so important? Should you teach them to your child and if so, what’s the best way to do this?

Contents:

- What Are Sight Words?

- Should You Teach Sight Words?

- Different Approaches to Teaching Sight Words

- What’s the Best Way to Teach Sight Words?

- Beneficial Rote Learning

- Learning to Spell Sight Words

- Does Memorising Sight Words Improve Fluency?

- The Illusion of Rapid Progress

- Sight Words and Comprehension

- Sight Words Can’t Be Sounded Out!

- Teaching Phonics and Sight Words Together

- Further Information

- References

What are sight words?

We define sight words as high-frequency words in this article. That’s because all the various lists of sight words are made up of the words that appear most often in print.

Unfortunately, there’s no standard definition for sight words and people also describe them using different names such as ‘core words’, ‘Dolch words’, ‘Fry words’ and even ‘popcorn words’.

We found the following definitions of sight words on various websites after doing a quick search online…

- “Sight words are words that are most frequently used and they appear on almost every page of text. These are also words that can’t necessarily be sounded out, so they need to be memorized.”

- “Sight words are words that are immediately recognizable and do not need to be decoded.”

- “Sight words are the words that are used most often in reading and writing. They are called “sight” words because the goal is for your child to recognize these words instantly, at first sight.”

- “Sight words are words that occur so frequently in written language that your child should just know them automatically on sight. They often do not follow the rules of phonics.”

- “A sight word is a word that can be read instantly, without conscious attention.”

You will notice that several of the descriptions above suggest that sight words need to be recognised instantly without the need to decode them or ‘sound them out’.

The aim is to get children to read the words without having to pay any conscious attention to the letters. This is a worthwhile goal because once children can recognise words automatically they can devote more of their attention to the meaning of the passage they are reading.

All the same, we don’t think it’s necessary to include this point in a definition of sight words.

That’s because the aim of good reading instruction is to get children to the point where they can read almost every word in a passage automatically.

If they can’t do this then they can’t read fluently.

Perhaps the most well-known source of sight words is the ‘Dolch word list’, which is made up of 220 common ‘service words’ and 95 high-frequency nouns. The list was compiled by an American psychologist in the 1930s and contains words that were the most common in children’s literature at that time.

An updated and expanded list of 1000 words was produced by another American academic called Edward Fry in the 1990s. This is often referred to as the Fry word list.

There are various other sources of high-frequency words, for example, the UK governments phonics guidance booklet, Letters and Sounds, included a list of 300 high-frequency words from the Children’s Printed Word Database, which was compiled in 2003.1

Click on the following link to download a free copy of this high-frequency word list.

The list on this Wikipedia link was compiled by researchers from the Oxford English Dictionary.

The exact order of which words occur most frequently varies a bit between sources because it depends on the texts that were used in the research. However, many of the words in the alternative lists are the same and everyone seems to agree that ‘the’ is the most commonly used word in written English.

According to Wikipedia, between 50% and 75% of all words used in school books, library books, newspapers, and magazines are a part of the Dolch word list.

Fry found that around 300 words make up approximately 65 percent of all written material.

Should You Teach Sight Words?

The simple answer is yes. Very few people would argue against children being taught to read sight words because they appear so often in print.

However, there is some disagreement about when and how these words should be taught…

Different Approaches to Teaching Sight Words

There are 2 main ways that sight words are usually taught:

- By strategies that encourage the rote memorisation of whole words.

- By strategies that encourage children to figure out the words by focussing on the letters in them and the sounds they represent (phonics instruction).

Although some educators claim to use a variety of strategies for teaching sight words, many of them are just based on rote memorisation, with different ways of drilling the words into children by constant repetition.

There is also some variation in when sight words are introduced to children.

Some educators recommend that the first sight words should be taught before children have had any phonics instruction, whereas others only teach sight words after children have developed a basic grasp of phonics. Another option is to teach sight words alongside phonics.

Individual sight words are sometimes grouped together in different ways and introduced in different sequences.

For example, in the US, Dolch words are commonly divided into groups by grade level, ranging from pre-kindergarten to third grade, with a separate list of nouns.

The groups of words are compiled by the frequency in which they appear in texts, not by their level of difficulty. So the words on the first list are found more often than words on the other lists.

Similarly, Fry words are often taught in order of frequency. For example, the first 100 most frequent words might be taught in Grade 1, the next 100 in Grade 2 and so on.

An alternative approach is to group sight words according to how difficult they are to decode using the principles of phonics. Words with similar spelling patterns can also be taught together with this approach.

Words that follow the most basic alphabetic code are taught first followed by words with more complex spelling patterns.

What’s the Best Way to Teach Sight Words?

There are different opinions about this but we strongly favour teaching sight words using synthetic phonics rather than asking children to memorise them as whole words.

We prefer the phonics approach because numerous studies have shown that systematic synthetic phonics is the most effective way to teach children to read.

In contrast, rote learning sight words is extremely inefficient because children don’t develop an understanding of how words are put together and the knowledge isn’t transferable (see beneficial rote learning below).

There are other potential drawbacks associated with rote learning words from their shapes that we discuss in more detail in our article about learning whole words.

Spelling expert Alison Clarke, has highlighted some of the problems of teaching sight words by rote in her excellent ‘Spelfabet’ website.

Beneficial Rote Learning

We’re not suggesting that rote learning is always bad, it can sometimes be beneficial.

For example, learning multiplication tables in mathematics can greatly reduce the time it takes for a child to do some types of calculations. It can also reduce the amount of mental processing they need to do when they are solving more complex problems.

And it’s helpful to memorise some basic facts if this knowledge is transferable and can be used to minimise the amount of information that needs to be learned in the long-run.

For example, if we consider mathematics again, children need to learn that each of the digits from 0-9 represent a particular amount of things. They also need to learn that for 2-digit numbers the first number represents tens and the second number represents units. Later, they are told that for 3-digit numbers the first number represents hundreds, the second tens and so on.

Learning this knowledge is helpful because once these representations and rules have been mastered, children can read virtually any number they encounter almost instantly. However, children do struggle to apply their knowledge at first and they need a bit of practice before they can read numbers fluently.

The alternative to learning the basic number facts we described above would be to get children to memorise say the first thousand numbers and hope that they could figure out how the number system worked for themselves.

But, fortunately, most people realise this would be a much less efficient way to learn.

Similarly, in phonics, children learn to recognise the letters and the sounds they represent and they do this by rote memorisation.

However, learning the letter-sound relationships and other phonics skills is beneficial because once children have grasped how the alphabetic code works they can read thousands of words without having to memorise each individual one.

Letter/sound knowledge is transferable knowledge in the same way the basic number facts are. It’s also meaningful knowledge because it helps children understand how our alphabetic writing system works.

Learning all of the letter-sound relationships takes more time than learning the basic number facts we mentioned above because there are various letter combinations and alternatives that need to be memorised for some sounds in English.

But, importantly, there are far fewer phonics rules and facts to learn than there are words to learn in the various sight word lists.

To put it simply…

“Getting children to memorise sight words is like throwing them some fish. Teaching them phonics is like showing them how to fish.”

Learning to Spell Sight Words

When children memorise whole words by rote they tend to focus more on the overall shape of the words rather than their individual letters.

This makes it hard for them to remember the spellings of the words and it’s a major disadvantage of the whole word approach compared to phonics.

Some teachers do get children to spell out sight words as well as memorise them but this is often made less effective because they get children to say the letter names without considering the sounds that make up the words.

Letter names are quite different from the sounds the letters represent.

As we discuss in our spelling with phonics article, it’s essential for children to break words down into their individual sounds when they are spelling because once they’ve internally vocalised the sequence of sounds in a word they can link these to the letters that represent those sounds.

This teaches children a fundamental principle of spelling:

– the letters in words are not arranged randomly, they are linked to the order of the sounds in words.

If the relationships between letters and sounds are ignored altogether, then children are left with the daunting task of trying to memorise the sequences of individual letters in each word by rote.

If we do a rough estimate and say that the 315 Dolch words have an average 3 or 4 letters per word, learning their spellings by rote is like having to learn over 300 strings of random 3 and 4 digit numbers. No wonder so many children have problems with spelling!

Learning spellings phonetically is far more efficient than this because the sequence of the sounds in each word provides children with important information about the sequence of the letters.

Does Memorising Sight Words Improve Fluency?

One of the most common reasons for getting children to rote-learn sight words is to allow them to recognise the words instantly. This is supposed to improve their reading fluency.

Yet, while the strategy probably does improve a child’s fluency for reading the particular words they’ve learned, it’s unlikely to improve their overall reading fluency.

That’s because a child’s overall reading fluency is much more dependent on their phonics skills than their ability to memorise sight words.

Children can learn to read a much wider range of words fluently using their phonics skills if they are given sufficient decoding practice. This is even true for words they haven’t met before.

As an example, imagine you were reading a book about friendly aliens with your child. Suppose some of the aliens had the following names:

Teb Hib Quog Blop Pilf Grunk Shug.

Our guess is that you can read these alien names quite easily and quickly, even though you’ve probably never encountered them before.

If that’s the case, it’s because you understand the alphabetic code and can blend the sounds represented by the letters sub-consciously in your mind.

The ability to do this doesn’t develop overnight, but it develops more quickly if children are given clear phonics instruction and plenty of practice.

Unfamiliar words crop up all the time in children’s literature.

For example, in Harry Potter, there are characters such as Snape, Voldemort, Dobby, Dumbledore and Hagrid. None of these words appear on any sight word lists, yet children with good phonics decoding skills can still read them fluently.

So, if you want your child to be able to read a wide range of words fluently, investing time practising their phonics skills is likely to provide a greater return in the long-term than time spent rote learning sight words.

The Illusion of Rapid Progress

Getting children to rote learn sight words rather than sound them out using phonics gives the illusion they are making faster progress because the initial results are more noticeable than the outcomes from early phonics instruction.

It takes time before beginning readers can decode an appreciable number of words fluently using phonics, but children can recognise an impressive number of words relatively quickly if they learn to recognise the overall shape of the words by rote.

However, progress often slows considerably as a greater number of sight words are introduced.

One reason might be that children find it increasingly difficult to distinguish between words because lots of them have very similar shapes.

The stunted progress could also be due to something called the interference effect. This has been observed with various types of rote learning and it can be quite a significant…

For example, in one study, a group of volunteers were asked to learn a list of 10 items and could recall 70% of the items after 2 days.

However, another group who had to learn a second list the day after learning the first one could only recall 40% of the items.

A separate group who learned a third list could only recall 25% of the items. 2

A similar problem has been observed in studies where people were asked to memorise unfamiliar whole words…

In one experiment, researchers created an invented alphabet and stacked the letter symbols on top of each other, rather than side-to-side.

A group of volunteers was asked to learn the words as whole shapes and they made good progress on the first day. However, on following days, when new lists of words were introduced, they quickly forgot the earlier words they had learned. 3

Another consideration is that when children spend time rote learning whole words they will have less time available for phonics practice.

This means it will take them longer to develop the sort of fluency they need to read the much wider variety of words they will encounter in real books.

Also, many of the words that appear in sight word lists are very simple and can be learned much more efficiently using very basic phonics rules.

For example, the following words are found in the Dolch pre-k list and kindergarten lists:

Up, in, it, big, can, not, red, run, am, at, but, did, get, on, ran, well, will, yes.

And even in 2nd and 3rd grade, when children have had several years of reading instruction, some schools encourage students to learn the following Dolch words by sight:

2nd grade:

Best, fast, its, off, pull, sit, tell.

3rd grade:

Cut, drink, full, got, hot, if, pick, seven, six, ten.

This contradicts the idea that learning words as whole shapes allows them to make faster progress. Most children should be able to read all of these words fluently after just a few months of synthetic phonics instruction. And dozens more words as well.

More alarmingly, the following Fry words are in the lists suggested for grade 4 and grade 5:

Sun, dog, stand, red, top, best, black, wind, fast, step, map, plan, ten, box, less, class, rest, ran, yes, yet, full, hot, am, six.

There’s something seriously wrong with the reading instruction in some schools if they find it necessary to make children rote-learn words like these at this stage in their education!

Sight Words and Comprehension

It’s claimed that memorising lists of sight words improves children’s reading comprehension because this makes it possible for them to recognise more of the words on each page of a book.

This argument sounds reasonable because sight words occur more frequently in print than other words.

For example, Fry found that the first 100 words in his list make up approximately 50% of the words in an average piece of writing.

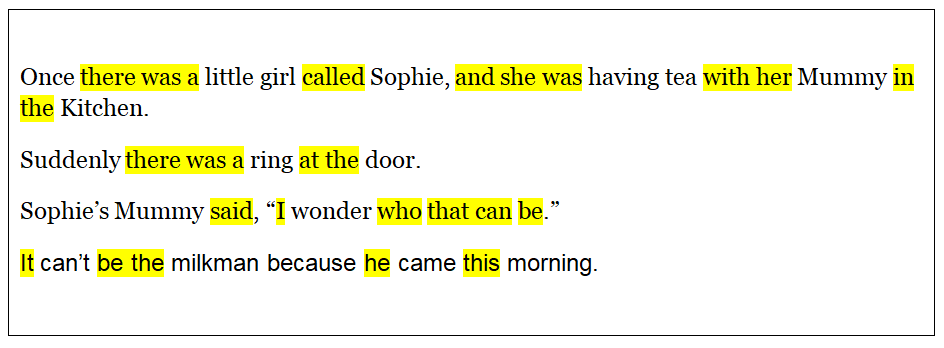

To illustrate this, we’ve copied the first few lines of a popular children’s book below and highlighted the sight words that are in Fry’s first 100 words list.

It’s recommended that these 100 words should be mastered by children at the end of grade one.

As you can see in this example, more than half of the words in the passage are indeed sight words, and at first glance, it looks as though a child could figure out the gist of the passage based on these recognisable words.

But this impression might be misleading because you can also read the non-sight words.

For children who’ve memorised sight words but haven’t learned to decode words using phonics, most non-sight words will be illegible.

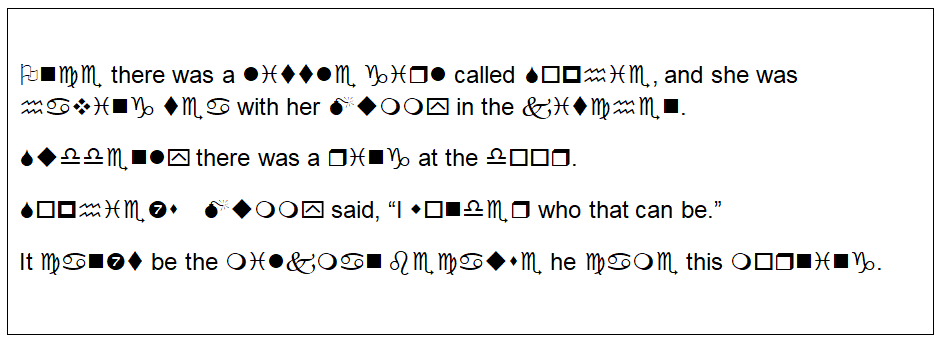

To simulate a child’s experience, we’ve converted the non-sight words into an illegible font below. Notice that the passage becomes much less clear…

To have really good comprehension of a passage, we need to be able to read almost all of the words in it.

Unfortunately, it takes time before a child will be able to recognise a broad enough range of words to read and understand children’s books independently, no matter what method of reading instruction is used.

Some teachers attempt to give their students a short-cut to comprehension by getting them to learn even more sight words. But as we discussed in the previous section, it gets harder to rote learn sight words as a greater number of them are introduced.

And even when children do learn new sight words successfully, they get diminishing returns from them…

Although the first 100 Fry words make up approximately 50% of the words in an average piece of writing, memorising the next 200 Fry words would only allow children to read an extra 15% of the words on an average page!

This means that more than a third of the words on an average page would still be incomprehensible.

And although memorising sight words allows children to recognise the words that occur most frequently on an average page, these same words will keep repeating throughout virtually every page in a book.

Children with basic phonics skills (who haven’t memorised sight words) probably can’t recognise as many words on an individual page, but they might be able to read a greater variety of words in a whole book.

Unfortunately, there’s no quick fix for reading comprehension and it relies on more than just word recognition skills as we discuss in our article on the subject.

In many schools and reading programmes, there seems to be a rush to get kids reading whole books independently when they’ve only just started reading instruction.

We think this is a mistake because they need to absorb some important knowledge and master a variety of skills before they can do this successfully.

This is similar to the way a child might learn to play a sport such as tennis. It takes some months of practice before a beginner is likely to get much benefit from playing a competitive game.

They need to learn the various strokes, stances and rules to a reasonable level first or they will spend most of their time hitting the ball into the net or out of court.

Some reading programmes use predictable and repetitive books and these can give the impression that youngsters are reading fluently with good comprehension.

But it might just be that children are able to figure out patterns in the texts due to the recurring phrases. Illustrations can also make it easy for a child to guess the one or two different words on each page.

If a child is presented with a less predictable passage that doesn’t contain illustrations, he or she might struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text.

Alison Clarke has made a very good video clip outlining the problems children would encounter if they actually attempted to read the words in these books without the help of the repetitive phrases and pictures:

Some phonics programmes encourage the use of ‘decodable books’ which mainly contain words that can easily be sounded out by beginning readers.

These can be beneficial for decoding practice and confidence, but they invariably have very simple storylines so aren’t very challenging in terms of comprehension development for children of school age.

Aside from learning to decode words phonetically, the most important thing for developing good comprehension skills is for an adult to read proper, interesting books with a child every day. But the adult needs to do more than just read to the child…

- They should allow the child to read some words that are appropriate for their stage of development and gently correct any errors.

- They should talk about the meaning of unfamiliar words to improve the child’s vocabulary.

- The adult and child should discuss the characters and what’s going on in the story and ask questions about it.

Doing this properly takes some time and effort. But it will do far more to build good comprehension than learning a bunch of sight words parrot fashion or allowing a child to plough through a series of repetitive and predictable books.

For more information about developing reading comprehension, see our articles on this topic.

Sight Words Can’t Be Sounded Out!

It’s often claimed that sight words need to be learned as whole words because most of them can’t be sounded out using phonics rules.

This isn’t strictly true because, as we’ve already seen, there are some very simple words in popular sight word lists such as ‘it’, ‘at’, ‘big’ and ‘red’ that can easily be sounded out by children with basic phonics skills.

In fact, when we analysed a list of the most frequent 300 words, we found that around half of them were completely regular and followed exactly the phonics rules taught in most synthetic phonics programmes.

Although approximately half of sight words aren’t completely regular, most of them have some common spelling patterns in them which can help children deduce what a particular word might be.

And some of the irregular spelling patterns occur in other common words, so children can learn to recognise these if they are shown them.

For example, the word ‘could’ is made up of 3 sounds: [c], [oul], [d] and only the second sound is represented by an unusual letter pattern. This same letter pattern appears in some similar sounding words that are also fairly common – ‘should’ and ‘would’.

The most common word in written English, ‘the’ is irregular because the letter e doesn’t represent its usual sound in the word. However, the letter combination ‘th’ is taught in many systematic phonics programmes and is found in other common words such as ‘this’, ‘that’, ‘then’, ‘than’ and ‘them’.

Alison Clarke from Spelfabet provides more examples in the short video below:

Research that shows phonics knowledge helps children to read all types of words, not just the regular ones. 4

Even when there are no obvious phonetic patterns in a word there are sometimes structural relationships between words that can help with reading and spelling them.

For example, the word ‘one’ has a very irregular spelling pattern.

If we think about the meaning of the word ‘one’, it represents something that is single, solitary or unique. We can then look for its relationship to other words with similar meanings such as only, once, and alone. As you can see, not only do these words share similar meanings, but they also share a similar spelling pattern.

We see a similar connection between the words twin’, ‘twice’, twenty and ‘two’.

Showing children patterns like these is much more effective than rote learning because we remember things much better when we can make connections and identify meaningful relationships between them.

We describe how to teach children to read irregular words and how to spell them in some of our other articles.

Teaching Phonics and Sight Words Together

Many educators believe that teaching children to rote-learn sight words alongside phonics instruction is the ideal approach.

This sounds like a good idea because it could allow children to recognise some of the most common words quickly while letting them develop their decoding skills at the same time.

However, we think this approach has some disadvantages which could outweigh any potential benefits:

- As we’ve already mentioned, rote learning is very inefficient.

It’s only really worth doing it if there’s no other way the information can be learned or if the knowledge that’s memorised can reduce the amount that needs to be learned in the long-run.

Neither of these things applies here; children can be taught to read virtually all of the sight words without resorting to rote memorisation.

- Learning whole words alongside phonics also gives children a mixed message that could mislead them…

Early success learning sight words by rote could give them the impression they don’t need to worry about letter-sound relationships and decoding. This could cause serious problems later on when they need to read words they are less familiar with.

And as we mentioned earlier, focussing on whole words rather than letters can have harmful effects on a child’s ability to spell.

- It can be confusing for children to be told they need to learn some words one way and others by a different method.

For example, teaching children that they should decode ‘dig’ using phonics, but they should learn ‘dog’ as a whole word doesn’t make a lot of sense to a beginning reader.

- Teaching irregular or more complex words to beginning readers before they’ve mastered the basics could make it harder for them to understand the principles of phonics.

For example, the Dolch Pre-K sight word list includes the following words:

a, and, away, big, blue, can, come, down, find, for, funny, go, help, here, I, in, is, it, jump, little, look, make, me, my, not, one, play, red, run, said, see, the, three, to, two, up, we, where, yellow, you.

Synthetic phonics programmes usually start by getting children to learn the most common sound that each letter in the alphabet represents. They then learn to read by ‘blending’ the letter sounds in words together.

Unfortunately, some of the letters in the words highlighted in red above don’t represent their most common sounds.

Consider the words ‘to’ and ‘go’; the sound represented by the letter ‘o’ is completely different in these two words, and both these sounds are entirely different from the sound that ‘o’ represents in regular words like ‘hot’ or ‘dog’.

Similarly, some of the letters in other irregular words like ‘said’, ‘one’, ‘two’ and ‘where’ are exceptions to the basic rules of phonics.

We don’t think it’s helpful to teach beginning readers exceptions to the rules before they even fully understand what the rules are.

Even some phonetically regular words can confuse children if they’re introduced too early.

For example, in the word ‘down’, the letter combination ‘ow’ isn’t normally taught until later in phonics programmes when children learn phonetically related words such as ‘clown’, ‘brown’ or ‘cow’.

Beginning readers who haven’t been taught this letter combination would be puzzled by the spelling of down.

Similarly, the words ‘away’ and ‘play’ contain another letter combination that’s taught later in phonics programmes: ‘ay’. This is found in words such as ‘day’, ‘say’, ‘clay’, ‘stay’ and ‘bay’.

Of course, children do need to learn how to read these words eventually, but they’re not an ideal introduction for kids who are just beginning to learn how letters in the alphabet correspond to individual spoken sounds.

It’s a bit like teaching negative numbers in mathematics before children have fully grasped basic addition and subtraction.

Alison Clarke discusses some of these problems in this article from her excellent ‘Spelfabet’ website.

The problems we’ve described above are a consequence of teaching words in order of their frequency without considering their complexity.

It makes far more sense to adopt a systematic approach that starts with words with the simplest spelling patterns before moving on to groups of words with more complex and irregular spelling patterns.

Using this strategy means that the focus is on learning to read and spell the most common sounds in the language first, rather than the most common words.

This is more useful because it enables children to make sense of the alphabetic system and it also allows them to read a much wider range of both familiar and unfamiliar words.

Building a strong foundation, by concentrating on the basics, before moving on to more complex examples is a fundamental principle of good teaching.

We’re not the only ones who recommend this approach to teaching sight words. This well-referenced article from the International Literacy Association comes to similar conclusions. 5

What’s more, several studies have actually demonstrated that spending time learning sight words can be counterproductive…

Professor Diane McGuiness has outlined the results of 3 large scale studies that looked at the impact of different teaching activities on children’s scores in standardised tests6.

All 3 studies found that time children spent memorising sight words was a strong, negative predictor of reading skill. In other words, the more time the children spent learning sight words, the poorer their reading scores were!

Having said all of this, we do think there is some merit to introducing a few irregular high-frequency words once children have developed a grasp of the basic alphabetic code and can read and spell simple words such as CVC words.

We discuss our own strategy for teaching irregular words in more detail in our article on high-frequency words and tricky/common exception words.

You can also see how this fits into an overall phonics teaching strategy if you view our article on phonics instruction.

Further Information

If you would like to know more about helping your child with their reading comprehension then click on this link: ‘Reading Comprehension Basics’.

We also have another article on Reading Comprehension Strategies.

References:

- Department for Education and Skills (2007), Letters and sounds: principles and practice of high quality phonics: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/letters-and-sounds-principles-and-practice-of-high-quality-phonics-phase-one-teaching-programme

Tables from: Masterson, J., Stuart, M., Dixon, M. and Lovejoy, S. (2003) Children’s Printed Word Database: Economic and Social Research Council funded project, R00023406 - Interference Theory, Wikipedia, Research with lists: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interference_theory#With_lists

- Nurture a Reader Blog. Learning Words as Whole: An Experiment (Oct. 2011). Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention, Stanislaus Dehaene (pp. 225-226): http://nurtureareader.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/learning-words-as-whole-experiment.html

- Synthetic phonics and irregular word reading: Cause for concern?: http://www.drsarahmcgeown.blogspot.co.uk/2014/08/synthetic-phonics-and-irregular-word.html

- Duke, N.K, and Mesmer, H.A.E. “Teach Sight Words as You Would Other Words.” Literacy Daily, International Literacy Association. June 2016: https://www.literacyworldwide.org/blog/literacy-daily/2016/06/23/teach-ldquo-sight-words-rdquo-as-you-would-other-words

McGuiness, D. A Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code, RRF Newsletter 49: http://www.rrf.org.uk/archive.php?n_ID=95&n_issueNumber=49