Find out the essential things you need to do if you want your child to develop good comprehension skills…

We describe the basics of teaching kids reading comprehension in this article and cover some additional comprehension strategies in a separate article.

Disclaimer: We support the upkeep of this site with advertisements and affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you click on the ads or links or make a purchase. There is no additional cost to you if you choose to do this.

What is Reading Comprehension?

Reading comprehension is the ability to understand whole sentences and paragraphs in texts. To comprehend a written sentence, a student needs to be able to decode the letters in the words, grasp the meaning of the individual words and phrases in the sentence and understand how they are linked. They might also need to identify how the main ideas in each sentence are connected and link these ideas to what they already know in order to draw conclusions and understand fully what the author is trying to communicate in a paragraph.

In longer, or more complex texts, students might also need to have some background knowledge about the theme that helps them understand the overall context of the story or article, and they might also have to make some inferences along the way.

Concentrate on Decoding Skills First by Teaching the Principles of Phonics…

Phonics and reading comprehension are closely connected. Your first priority is to make sure that your child can identify words from the letters that make them up, this is known as decoding.

Having a good working knowledge of phonics is the most reliable method of identifying words.

Some educationalists are critical of early phonics instruction, but its importance for comprehension becomes clearer when you understand the key skills involved in reading…

The Simple View of Reading

Most academics acknowledge that reading is a complex activity. Understanding a piece of extended writing involves the interaction of various mental processes.

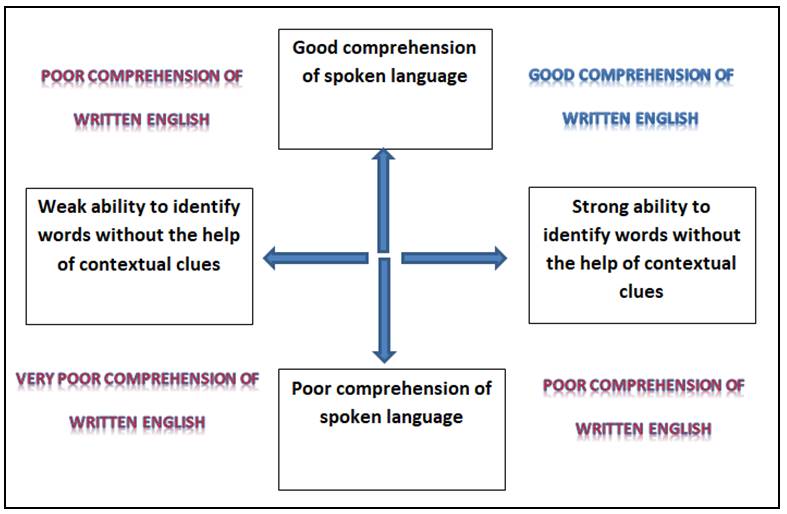

Yet, in spite of its complexity, there is a widely accepted model called ‘the simple view of reading’ that identifies two key skills which are essential for proficient reading: 1

- The ability to recognise words(without the help of contextual clues) and

- language comprehension skills (the ability to understand what spoken words and phrases actually mean).

Notice that in this representation of the simple model, only children who have both of the essential skills will have good comprehension of written English.

Phonics instruction plays an important role because it develops the word recognition skills of beginning readers. Children taught phonics learn to decode words by identifying letters and the sounds they represent.

This is the most fundamental skill in learning to read because most children already have a reasonable level of language comprehension when they start school. However, their ability to recognise words in texts is usually very poor at this stage.

Although figuring out a word doesn’t guarantee that a child will understand it, it’s impossible to comprehend text unless the words can be identified quickly and accurately.

This can be illustrated by looking at a simple sentence that’s written using a different alphabet. For example, look at this sentence written in Arabic:

كان الصبي متحمسا عندما رأى سيارة سباق حمراء.

The sentence says: “The boy was excited when he saw a red racing car.” Even if you could speak Arabic, it would be impossible to comprehend the written text unless you had a decent knowledge of the Arabic writing system.

Phonics instruction teaches children the relationships between letters in our alphabet and the sounds they represent. Without this knowledge, writing can look like a bunch of mysterious squiggles to beginning readers – much like the Arabic example above.

Critics of the simple view of reading point out that there are other important factors involved in the reading process:

“There is much more to word identification than synthetic phonics and much more to text comprehension than understanding spoken language. We need to interpret the terms of the equation with care and recognise its limitations.” 2

But supporters of ‘the simple view’ point out that while it is neither a complete description nor a complete explanation of reading, the two skills it identifies are the most important components in the reading process. 3

This claim is supported by research…

“Across the school years, reading comprehension is almost perfectly predicted by a combination of two tests: a test of decoding skills and a test of listening comprehension (combined correlation is around .90). This body of research is so consistent that the statistical values from one study to the next are almost identical.” 4

“In line with the simple view of reading, listening comprehension, and word decoding, together with their interaction and curvilinear effects, explains almost all (96%) variation in early reading comprehension skills. Additionally, listening comprehension was a predictor of both the early and later growth of reading comprehension skills.” 5

Irrespective of the simple view of reading model, a variety of educational studies have shown that phonics instruction is beneficial for reading comprehension.* So if you suspect your child’s phonics skills aren’t as good as they should be, focus on improving these first.

*We discuss some of these studies in our article: “Does Phonics Help With Reading Comprehension?”.

If you would like to know more about teaching your child phonics, see our article “How to Teach Your Child Phonics”.

Help Your Child to Develop Good Comprehension of Spoken English…

Although learning phonics is important, the simple view of reading tells us that it’s not enough on its own.

Cultivating good oral language skills is equally important because we use the same processes to make sense of spoken language as we use to understand written text.

So, once children can read written words fluently, their reading comprehension is largely dependent on their comprehension of spoken language.

Professor Dianne McGuinness has pointed out that once a child can successfully decode a large number of words they could actually improve their their comprehension without doing much extra reading, as long as they developed their spoken language skills by engaging in meaningful conversations.4

However, reading is still important because it exposes children to a wider range of vocabulary and ideas than they are likely to meet in ordinary conversations.

In order to understand spoken dialogue, or written text, children need to be familiar with the vocabulary* used and the basics of grammar.

*See our article about improving vocabulary.

It isn’t essential for very young children to learn grammatical terms, such as pronouns, adjectives and prepositions, but they do need to have an informal understanding of the way words and sentences are constructed.

Fortunately, children have an innate ability to grasp spoken language and they can learn the basic rules unconsciously by listening to adults during conversations.

For example, they soon learn that if you add an ‘s’ to the word ‘dog’ you are talking about more than one, and they can figure out the difference between ‘walk’ and ‘walked’.

Children can also develop an impressive vocabulary without any formal instruction. Even so, their development shouldn’t be taken for granted because they need the right sort of stimulation to achieve good levels of verbal comprehension. As Professor Pamela Snow, a speech pathologist has pointed out:

“… children’s acquisition of oral language, while strongly “pre-programmed” in an evolutionary sense, still requires enormous environmental input and interaction, in the form of exposure, simplification, repetition, imitation, expansions, recasts, and so on”. .. Oral language, then, is one of those deceptively complex processes that by virtue of its pervasive presence in our lives can appear simple, or even inconsequential, as a developmental achievement. It is neither. “ 6

A very simple, but important, thing to do is to give your child regular conversation time that’s free from distraction.

It’s not uncommon to go into a house where there are young children and find that the TV is switched on all the time. On top of this, the children might be playing with noisy electronic toys and the parents might be engrossed on their smart-phones.

Unfortunately, children find it hard to focus on the sounds and meanings of words when they’re distracted by competing noise and they seem to respond to direct conversation from a person much better than they do to words coming from a screen, even if it’s a quality programme.

Most parents use TV or electronic devices to entertain their kids nowadays, so you don’t need to feel guilty about giving your child a bit of screen time, but do try to set aside some slots of time every day when you can give them your undivided attention.

When you see your child showing an interest in something, start a conversation about it; ask questions and listen carefully to the answers. See if you can extend the dialogue by saying things like:

- “I really enjoy doing ‘this or that’ because ……,

why do you like playing with ….?

- What do you think would happen if we did ………..?

Ask them about their favourite foods, what they like about them and why they don’t like some things.

If you keep in mind the question starter words from Rudyard Kipling’s short poem you won’t go far wrong:

I Keep six honest serving-men:

(They taught me all I knew)

Their names are What and Where and When

And How and Why and Who

Talk about things you see when you are out and about and talk about TV programmes you watch together. Try to find something new to add to their vocabulary and knowledge base every day. It might be an object, an action, a colour, a texture or an interesting fact.

Do nursery rhymes together and discuss what they mean and who the characters are. Explore songs together in a similar way.

Perhaps the most important thing you can do for both verbal and written comprehension is to read to your child. We discuss how to get the most out of reading books with your child later in this article.

Improve Your Child’s General Knowledge

Although good decoding skills, a reasonable grasp of grammar and a broad vocabulary are necessary for reading comprehension, they aren’t always sufficient.

Studies have shown that it’s important for us to have some background knowledge about the subject of the text we are reading.

For example, consider the following text:

‘The campfire started to burn uncontrollably. Tom grabbed a bucket of water.’

It might seem obvious to an adult that Tom grabbed the bucket of water because he wanted to put the fire out.

But for a child to make this inference, and comprehend the link between these two sentences, they would need to be aware of the possible consequences of a fire burning out of control. And they would also need to have the background knowledge that water can put out fires.

Even a child with a good vocabulary would find it impossible to see the connection between the two sentences if he or she was lacking the essential background knowledge.

Authors miss out lots of basic information when they write because it would make their passages boring if they mentioned every detail and explained the motives of every action or reaction made by their characters in a story.

They expect the readers to make inferences from the information in the passages and to fill in the gaps using their own experiences and knowledge of the world around them.

Consequently, if children are to develop good all-round comprehension, they need a broad range of knowledge from real-life experiences and from a variety of books or other educational sources.

Real-life experiences could include discussions about their own feelings and actions at different times and educational experiences might include visits to museums, places of historical interest or anywhere they can see and discuss the natural world.

Educational TV programmes and children’s news programmes can also play a role in building general knowledge.

The importance of a variety of textual sources was highlighted in a guidance document published by the UK government:

“Good teaching will exploit, for example, the power of story, rhyme, drama and song to fire children’s imagination and interest, thus encouraging them to use language copiously. It will also make sure that they benefit from hearing and using language from non-fictional as well as fictional sources. Interesting investigations and information, for example from scientific and historical sources, often appeal strongly to young children” 7

Cognitive neuroscientist, Professor Daniel Willingham, has written about the importance of developing a good level of general knowledge to support reading comprehension.8

He recommends providing children with reading materials that teach them about the world, which is similar to the advice from the Letters and Sounds Publication above.

Professor Willingham’s video, Teaching Content Is Teaching Reading, provides a useful explanation and summary of this point:

Professor Wilingham also discusses the importance of general knowledge in reading comprehension in this article: School time, knowledge and reading comprehension.

The English programme of study for the UK National Curriculum also highlights the importance of good general knowledge for comprehension:

“Good comprehension draws from linguistic knowledge (in particular of vocabulary and grammar) and on knowledge of the world.” 9

Developing a good level of general knowledge is something that takes time – years rather than weeks or months.

Don’t try to cram in a lot of facts about one particular subject over an extended period; instead, try to vary the information your child is exposed to.

So, in one week you might do an activity related to history, the next week something science-based and perhaps something geographical in another week and so on.

Drip-feeding information in short regular intervals is the way to go, but don’t feel that you need to provide your child with educational activities every day of the week.

Nor do you have to do anything that’s extravagant. Reading a few pages of a non-fiction book 2 or 3 days a week or watching educational TV programmes every now and again can make a difference in the long-run, as can discussing things over the dinner table.

Re-visit topics as the months and years progress to help your child retain and recall the information and gradually explore some of the topics in more depth as they get older.

Schools will do much of this work for you, but supplementing what they do in class in a more relaxed and informal way, perhaps using alternative books, websites, TV shows or educational visits, will help to make your child’s knowledge broader and deeper.

One website that’s definitely worth checking out is WatchKnowLearn.org. This contains thousands of short educational videos on a wide range of topics, and it’s completely free. The videos are organised into different categories and can be filtered to be suitable for different age groups.

DK Find Out! is another excellent free resource. It’s a reliable online chidren’s encyclopedia that’s really well illustrated and it’s got quizzes, videos and animations. You can find out more about this website in the short video below…

How to Get the Most Out of Reading to Your Child…

You can purchase special books for reading comprehension, and these can be helpful. However, your child can also benefit enormously from reading ordinary story books and non-fiction books…

Whether you are reading to your child or your child is reading to you, it’s important that they grasp the idea that they need to monitor their own comprehension and think about what is happening in a story when they are reading. This applies to both the words and the pictures.

So, when you share a book with your child, try to look out for a range of educational opportunities; allow time to discuss the pictures, ask questions and explain new words as you go along to improve your child’s vocabulary and understanding.

Examples of the sort of questions to ask might include:

- “What’s happening in this picture?”

- “Who do you think is Dad and who is the pirate in this picture?”

- “Why do you think that?”

- “Do you think they look happy, sad or frightened?”

- “How many birds can you see on this page?”

- “What colour is the bus?”

- “Who is the tallest in this picture?”

- “Was that a good thing for Goldilocks to do?”

- “Why do you think she did that?”

- “What should she have done instead?”

- “What do you think that word means?”

Of course, you need to be careful not to fire too many questions at your child during the story or you could spoil it. The aim is to help your child get more enjoyment and meaning out of the book, not to interrogate them!

Read the whole story first, discussing one or two things as you go and then maybe go back through it a second time asking a few more questions, but always keep it relaxed and fun.

Also, don’t read for too long in one sitting, leave them wanting more so they can’t wait to read with you again.

Finally…

Reading and comprehending books should be an enjoyable activity that children look forward to.

It’s important to remember that a child needs to feel secure and supported by the adult working with him or her. Most of us have forgotten how difficult it is to learn to read fluently and so it’s easy to be overly critical when a child makes a mistake.

Children need to be confident that they can make mistakes without being chastised, otherwise, they will experience emotions like anxiety and frustration during the process and these feelings can distract their attention from the task at hand.

In fact, a reduction in performance due to anxiety can lead to even more anxiety creating a spiral of negative feelings that can lead to the child disengaging from the task altogether.

This doesn’t mean that you should avoid correcting your child if he or she makes a mistake, but you should always try to intervene in a caring, supportive and non-judgemental way.

Tell your child that it’s OK to make mistakes and that it’s a normal part of learning and try to give more praise for the effort they are making than for how successful they are at the task.

If you want to learn more about how to improve reading comprehension for kids, see our article, ‘Reading Comprehension Strategies’. See below for more information about reading help for kids.

Further Information…

The BBC Bitesize website has some useful information and child-friendly videos about comprehension.

If you would like more information about improving your child’s vocabulary, click on this link.

If you would like more information about the different approaches to teaching children to read, see our article:‘How Can I Teach My Child to Read?’

If you would like to know more about teaching your child phonics, see our article “How to Teach Your Child Phonics”.

References:

- Outlined in the Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading. Final Report, Jim Rose, 2006

- The Simple View of Reading – Explained, TeachingTimes.

- Rose (2006), Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading, Page 76, paragraph 12.

- McGuiness, D.,RRF Newsletter 51, A Response to ‘Teaching Phonics in the National Literacy Strategy’: http://www.rrf.org.uk/archive.php?n_ID=112&n_issueNumber=51

- Lervag, A., Hulme, C., & Melby-Lervag, M. (2017). Page 1, Unpicking the developmental relationship between oral language skills and reading comprehension: It’s simple, but complex. Child Development, 00(0), 1–18.

- If learning to read is a “linguistic task”, what’s wrong with Whole Language?: http://pamelasnow.blogspot.co.uk/2014/09/if-learning-to-read-is-linguistic-task.html

- Letters and Sounds: Principles and Practice of High Quality Phonics, Department for Education and Skills in 2007.

- Willingham, D, (2009) Why don’t students like school? Jossey-Bass.

- UK revised National Curriculum (updated July 2014): https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-english-programmes-of-study