Advice about Dyslexia can be confusing and contradictory. Is it a disability or a gift? What causes it and what are the best treatments? Find out here…

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below:

Contents:

- What Is Dyslexia?

- How Common is Dyslexia?

- What Causes Dyslexia?

- Controversies

- Are Dyslexic Children Different From Other Poor Readers?

- Diagnosing Dyslexia

- Is it Helpful to Separate Poor Readers into a Dyslexic Group and a Non-dyslexic Group?

- Are Dyslexic People Gifted In Other Ways?

- What Are the Best Treatments for Dyslexia?

- Can Dyslexia be Cured?

- Further Information

- References

Summary

- Definitions of dyslexia vary, but most refer to it as a learning difficulty or disability that affects people’s literacy skills. Some commentators suggest that dyslexic people can suffer from a broad range of problems, with reading difficulties being just one part.

- The amount of dyslexia in the population is uncertain. Some sources say that 5% of people have the condition and others say it’s as many as 20%. Since there is no universally agreed definition of dyslexia, it’s impossible to give a precise figure.

- Some schools use ineffective strategies to help struggling readers. Schools that provide early, appropriate and intensive interventions have lower numbers of dyslexic children.

- There doesn’t appear to be a single cause of dyslexia. A combination of inherited, environmental and lifestyle factors can have a negative impact on a person’s ability to read.

- The complex English spelling system is thought to make things even more difficult for dyslexic people in English speaking countries.

- Dyslexia can be a controversial topic because there is disagreement about how it should be diagnosed and treated.

- There is also some dispute about whether or not people with dyslexia are actually different from other poor readers.

- People with dyslexia have brains that are structured differently and function differently than the brains of good readers.

- There is evidence that reading difficulties can be inherited and scientists have identified regions in the human genome that correlate with reading ability. However, each of these regions only explains a very small amount of the variation in reading ability between individuals (less than 0.5%).

- Assessments for dyslexia include more than just checking a person’s reading or spelling ability. Other things assessed might include phonological awareness, IQ, short-term memory and processing speeds. Assessors might also look for evidence of more general traits such as disorganisation and clumsiness.

- There is no agreement on which specific symptoms need to be present for someone to be diagnosed as dyslexic, so different clinicians might use different tests to assess for the condition and they might interpret the results in different ways.

- Some people argue that being assessed as dyslexic can be beneficial in a number of ways: it provides official recognition that there is a problem, might lead to extra support and might have a positive impact on a child’s self-esteem.

- However, others, including a number of distinguished academics, say that it’s unhelpful and potentially discriminatory to separate people with reading difficulties into different groups.

- Opinions about whether or not dyslexic people have special talents seem to be mixed. Some studies have shown that dyslexics are no more creative than the average person, but there is evidence that dyslexic people are better at seeing ‘the bigger picture’ when presented with visual information.

- Dyslexic people have also been shown to be better at ‘causal reasoning’.

- A number of people have suggested that being dyslexic might actually be a gift and they point out that it can be an advantage in some areas. For example, a significant number of entrepreneurs have dyslexia and there are lots of famous dyslexic people in the entertainment industry.

- However, it isn’t clear whether this success is due to any special talents that are associated with dyslexia. It might just be that some dyslexics are more determined to overcome their difficulties and pursue their ambitions.

- It’s frequently claimed that famous geniuses such as Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison and Leonardo Da Vinci were dyslexic, but little evidence is produced to support these claims and they have been disputed.

- Whatever advantages might come with dyslexia, there are certainly some significant problems associated with the condition. Dyslexic people are far more likely to be excluded from school, more likely to have alcohol or drug-related problems and more likely to end up in trouble with the law.

- One-to-one carefully structured, explicit instruction, with a strong emphasis on phonics, has been shown to make the biggest difference to the reading abilities of children diagnosed with dyslexia.

- There is little scientific evidence that alternative treatments are effective. Children who haven’t grasped the basic alphabetic code might just need to have it explained more clearly, more slowly, more skilfully or more often until they get it.

- Dyslexic children who have a broader range of problems might always need support with some of their difficulties.

- However, many children who have been diagnosed as dyslexic can overcome their reading difficulties and go on to achieve academic success.

Click here for further information if you want to help your child with reading, writing or spelling.

Main Article

What Is Dyslexia?

The word ‘dyslexia’ has its origins in the Greek language; the prefix ‘dys’ means ‘bad’, ‘difficult’ or ‘impaired’ and ‘lexis’ means ‘words’. So, dyslexia literally means difficulty with words.

Scientific and educational definitions of dyslexia vary; in fact, as many as forty-two definitions have been listed in academic literature.1

Nevertheless, most definitions share some common ground and the condition is generally described as a learning difficulty or disability that mainly affects literacy. This can include problems with reading, writing, spelling, comprehension or all of these combined.

Up until recently, The British Dyslexia Association (BDA) listed several definitions on its website. The one adopted by its management board prior to 2019 was as follows:

‘Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling.

- Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed.

- Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities.

- It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut-off points.

- Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor co-ordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia.

The International Dyslexia Association (IDA) has adopted the following definition:

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

Although the above two definitions are subtly different, they essentially say many of the same things.

However, The British Dyslexia Association recently updated its description of dyslexia and it now highlights the problems dyslexic people face when they are processing information.2

Not all researchers, clinicians and teachers agree on what causes the condition and there are different views on the best ways to diagnose and treat it. The lack of a precise universally-accepted scientific definition of dyslexia may be partly responsible for these disagreements.

For example, in addition to the points in the above definitions, dyslexic people might be described in any of the following ways by different experts:

- anyone who struggles with accurate and/or fluent decoding,

- those who suffer from a broad range of problems of which reading difficulties are just one part. These might include poor motor, arithmetical, or language skills, visual difficulties, organisation difficulties, clumsiness and low self-esteem,

- people with some of the above problems even if they don’t have any serious reading difficulties,

- those whose reading difficulties cannot be explained in alternative ways (e.g. because of severe intellectual or sensory impairment, socio-economic disadvantage, poor schooling, or emotional/behavioural difficulty),

- those for whom there is a significant discrepancy between reading performance and IQ,

- those whose poor reading contrasts with strengths in other intellectual and academic domains,

- those who fail to make meaningful progress in reading even when provided with high-quality interventions.3

The above list doesn’t cover all of the different descriptions of people with dyslexia, but it illustrates some of the inconsistencies surrounding people’s understanding of the term.

How Common Is Dyslexia?

Reading ability has what is statistically known as a ‘normal distribution’ in the population, which means it varies in a similar way to things like height.

If you were to check the height of everyone in a country you would find there would be a few people who are exceptionally tall and a few people who are exceptionally small, but most people would be fairly close to the average height in their population.

Deciding the height that someone would need to be before they are classed as small is a matter of opinion. Should it be just below average height or well-below average? And if it is well-below average should it be the smallest 5% or the smallest 10%?

The same problem arises when we try to judge someone’s reading ability. Figures quoted for the amount of dyslexia in the population seem to be somewhat arbitrary, with some sources saying that 5% of the population has the condition and others saying it is as many as 20%.

Since there is no universally agreed definition of dyslexia, and since there isn’t even agreement as to whether being dyslexic is different from just being a poor reader (see below), it’s impossible to give a precise figure.

However, one point that’s sometimes used to identify the ‘true’ proportion of dyslexic children is how well poor readers respond to extra help (often called ‘response to intervention’). Some children make really good progress when they are given individual or small group support, but a few don’t seem to improve very much at all. The British Dyslexia Association stresses the importance of this point in their definition:

“A good indication of the severity and persistence of dyslexic difficulties can be gained by examining how the individual responds or has responded to well founded intervention.’

Some sources suggest that the number of children who don’t respond well to interventions is in the region of 4-5%, but even here there is room for some uncertainty as to whether this is always due to biological reasons.3 That’s because ineffective strategies are sometimes used to help struggling readers in schools.

One intervention programme we have witnessed being used in a local school quite recently involves encouraging children to guess words from the pictures in books. We discussed why this and similar so-called ‘multi-cueing strategies’ are not a good idea in our article ‘Phonics vs Whole Language’.

Children in the programme we observed get very little direct phonics instruction even though this has been shown to be the most important element of remedial reading instruction. Instead, they are told to read the same book to an adult over and over until they have memorised almost every word in the story.

We aren’t the only ones to express concerns about some of the interventions being used in schools. Susan Godsland discusses the problem at length in her very well-researched dyslexics.org.uk site 4

The UK Parliament’s all-party Science and Technology committee also questioned the use of word memorisation and ‘whole language’ reading strategies.5

Susan Godsland provides examples of schools in deprived areas of the UK that manage to get all of their pupils reading to an acceptable level.

All of these schools use synthetic phonics programmes when they are supporting struggling readers and they avoid using the questionable multi-cueing strategies we mentioned above. They provide intensive one-to-one phonics instruction until the children have caught up.

In some of these schools, no children have been identified as dyslexic for several years because they all learn to read at the expected standard! This suggests that the problems of some children who are identified as being dyslexic in other schools might be due to a lack of effective support rather than incurable biological deficits.

Another problem in some schools is that the children who’ve fallen behind often don’t get extra tuition from fully qualified teachers.

Ideally, a struggling reader should have one-to-one tuition with a specially trained teacher. But all too often in the UK, the interventions are done in groups with a teaching assistant. Many teaching assistants are very good, but, unfortunately, a number of those providing reading interventions have minimal qualifications and training.

Even when interventions are high quality, we mustn’t underestimate the effect of children’s motivation and emotional states on their progress.

When children realise they are struggling compared to others this creates feelings of anxiety. They might even feel ashamed, especially if they can’t figure out a word they’ve been asked to read in front of their classmates. Some children can even feel emotionally threatened by the prospect of extra reading practice and this can make them engage in avoidance behaviours.

Children would rather appear naughty than stupid, so inappropriate behaviour is common in low ability children, whatever the subject matter and whether they are dyslexic or not.

In a ‘fly on the wall’ documentary by the BBC, children in a small reading intervention group spent more time making faces and giggling at each other than they did focussing on their books.6

Even if they don’t misbehave, experiencing negative emotions makes it harder for a child to think. This causes them to perform even worse, which can further increase anxiety and create a negative feedback loop (vicious circle).

Finally, it takes a lot of time and effort to catch up. Children who grow up to be good readers of English have been read to, on average, for 30 minutes every day since they were very young.7 Unfortunately, children who don’t get a lot of support at home are unlikely to make sustained progress even if they experience high-quality interventions at school.

What Causes Dyslexia?

No single reason can fully explain why some groups of people have reading difficulties and others don’t.

As we mentioned in another article, reading and spelling are complex processes that involve the visual and auditory senses and many different parts of the brain working alongside each other. Mental processes involved in reading include:

- Visually recognising individual letters and combinations of letters.

- Making an auditory interpretation of the sounds they represent.

- Understanding how these sounds link together to form the grammatical structures and spellings of syllables and whole words.

- Working out the meaning of the words from the memorised vocabulary and the wider context of the sentence or whole text.

The cognitive processes of reading also involve using our working and long-term memories as we combine individual ‘sounds’ together to construct words while we retrieve the stored meaning of individual words and phrases.

For a good level of comprehension, all of these procedures need to be synchronised at speeds that are similar to the rate we process spoken language. Good readers process letters into sounds in less than a tenth of a second.8

Reading problems can potentially be caused by anything that creates a significant fault in any one of the stages in this process, or by a combination of things that produce slight deficiencies in several stages.

A combination of inherited, environmental and lifestyle factors can have a negative impact on the reading process.3

So dyslexia can be described as a ‘multifactorial’ condition (in the same way that some diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease which have multiple causes are classed as multifactorial disorders).

Auditory Problems

It’s been observed that people with severe hearing difficulties find learning to reading more difficult than those with normal hearing. However, the majority of dyslexic people don’t have severe hearing difficulties.

Perhaps the most common theory to explain dyslexia in the wider population is that dyslexic people tend to have poor phonological awareness.

This basically means they find it difficult to grasp the sound structure of spoken and written words. So a dyslexic person might find it difficult to tell if a word has 2 syllables or 3 and they might also have trouble identifying rhyming words. They may also struggle to recognise or discriminate between the most basic speech sounds (known as phonemes).

In the BBC 4 documentary on dyslexia, ‘Growing Children’*, Professor Usha Goswami of the Centre for Neuroscience in Education in Cambridge explained that poor phonological awareness is similar to colour blindness:

“People who are colour blind can still see, but they have difficulty in detecting fine distinctions between some colours like red and green.

Dyslexic children can hear, but they have trouble detecting the subtle changes in sound intensity from one syllable to the next in speech.”

This difficulty in distinguishing between different rhythmic sounds in speech makes it slightly more difficult for them to process language in their brains. This might also make reading more difficult as some of the same brain regions are involved in reading.9

However, although phonological problems seem to be important in explaining why some people might be dyslexic, they don’t provide a complete explanation of the problem. Some children with poor phonological abilities can go on to develop good reading skills. And some children struggle to read even if they have relatively good phonological awareness.3

Visual Problems

Many researchers believe that visual problems are not a major cause of reading difficulties. In a large study, teams from Bristol and Newcastle universities in the UK carried out eye tests on more than 5,800 children and did not find any differences in the vision of those with dyslexia. In fact, a large majority of dyslexic children were defined as having “perfect vision”.10

Report co-author Alexandra Creavin said eyesight was “very unlikely” to be the cause of such reading problems.

Yet, a recent French study found a key difference between the eyes of a group of dyslexic people compared to a group of non-dyslexics. Apparently, most of us have a dominant eye in the same way that people have a dominant left or right hand, but in the dyslexic group in the study, neither eye was dominant. The researchers believe this could affect the way they view text.11

This was a relatively small study that hasn’t been replicated, so it’s unclear how many dyslexic people might be affected by this problem. Prof John Stein, dyslexia expert and emeritus professor in neuroscience at the University of Oxford said that these findings were unlikely to explain everyone’s dyslexia.

It has also been shown that dyslexic children often have more difficulty maintaining their visual attention on print. A study found that about 60% of children who went on to become poor readers had visual-attention problems when they were in preschool.12

Other visual processing problems have also been proposed as explanations for dyslexia, including one that is apparently due to problems with the ‘magnocellular system’. This detects contrast, motion and rapid changes in the visual field. Defects in this system could make it harder to view sharp images of individual letters.

However, so far, studies have shown that problems in this area can only account for a small percentage of the variation in reading abilities of children. Furthermore, a significant number of those who show magnocellular deficits go on to become adequate readers and reading instruction also seems to improve the visual processing problems.13

Problems Due to Complex Written Languages

Studies have also shown that the complexity of the English writing system has an impact on the proportion of children who develop dyslexia.

Some countries (such as Finland, Spain, Italy and Germany) have a more consistent relationship between letters and sounds and this makes it easier for all children in those countries to learn to read. In Italy, it was found that there were only half as many 10-year-old children with dyslexia as there were in the USA. 14

Another study showed that Austrian dyslexic children could read twice as fast and read more accurately than English dyslexic children of a similar age.15

In fact, according to Susan Godsland, author of the dyslexics.org.uk website, in countries with simpler alphabetic codes they don’t even assess reading difficulties in the same way as we do in English speaking countries:

“In countries which have a transparent code and synthetic phonic teaching methods (e.g, Austria, Finland and Greece…) it is rare to find people who are very inaccurate word decoders i.e. dyslexic in the English-speaking world’s sense of the word.

English reading tests commonly assess accuracy of single word decoding but, because of the high word reading accuracy in countries with transparent codes, these tests are not used and reading fluency (speed and comprehension) is assessed instead i.e. the term dyslexia means something completely different in these countries” 16

Controversies

As we mentioned in our article, ‘Why Do So Many Children Struggle With Reading’, the vast majority of academics agree that dyslexia has neurobiological causes. Professor Julian Elliott, who has written a book about the dyslexia debate, has stated:

“Clearly, there are many children who struggle to learn to read for reasons other than poor teaching”.3

However, there is less agreement about how dyslexia should be diagnosed and treated and whether or not people with dyslexia are actually different from other poor readers.

Some commentators have argued that these disagreements are in part due to different groups involved in the dyslexia debate having different agendas:

- Parents, quite rightly, want their children to have their problems recognised and they want some support.

- Dyslexia support and lobby groups provide a voice for these parents and children.

- Specialist assessors and tutors in the dyslexia industry are under considerable emotional and commercial pressure to give the parents what they want.

- Schools are keen to avoid the threat of litigation and they welcome extra funding, but they might also have concerns about being able to provide enough support and resources for newly diagnosed dyslexic children.

- Scientists and other academic researchers are emotionally invested in their own particular theories about the causes and nature of the condition. This can bias their judgements if new evidence emerges that challenges their long-held views.

The views of politicians can also be influenced by the interests and concerns of the more vocal groups, and by information reported in the popular media that may or may not be accurate.

When the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee investigated literacy problems in 2009, they were critical that government policy had been overly influenced by the dyslexia lobby:

“We recommend that the Government be more independently minded: it should prioritise its efforts on the basis of research, rather than commissioning research on the basis of the priorities of lobby groups.” 17

Are Dyslexic Children Different From Other Poor Readers?

There is little dispute that there are observable differences between dyslexic people and skilled readers. However, there is less agreement about the differences between dyslexic people and other poor readers.

Brain Differences...

It’s common to hear or read statements like “dyslexic people’s brains are ‘wired’ differently”. And it’s true that modern imaging techniques have shown differences in brain activity between poor readers and skilled readers.

Dyslexia researcher and neuroscientist Dr. Gordon Sherman says that people with dyslexia have brains that are structured differently and function differently.18

Skilled readers generally show more activation in the left hemisphere than poor readers and there are some differences in the distribution of grey matter. However, currently, neuroscientists can’t reliably distinguish between children who’ve been diagnosed as dyslexic and other poor readers.3

The analysis of data from brain imaging is quite complex because a variety of areas in the brain are active during reading and there is much that neuroscientists don’t fully understand. There is also some evidence that the brain activation can shift towards a more ‘normal’ profile when poor readers are given intensive instruction.3

For example, a Spanish study showed that Columbian guerrilla warriors, who had never had the opportunity to learn to read as children, showed similar patterns in their brain structure as people with dyslexia. However, their brains normalised after reading lessons. 19

Dr. Manuel Carreiras who conducted the study said:

“This new study therefore suggests that some of the differences seen in dyslexia may be a consequence of reading difficulties rather than a cause.”

Dorothy Bishop, Oxford University Professor of Developmental Neuropsychology has stated:

“Most people assume that dyslexia is a clear cut syndrome with a known medical cause, and that affected individuals can be clearly differentiated from other poor readers whose problems are due to poor teaching or low intelligence. In fact, that is not the case.” 20

Genetic Differences...

Genetic influences on dyslexia have been inferred from twin studies which show that identical twins are more likely to have similar reading abilities to each other than non-identical twins do to each other.

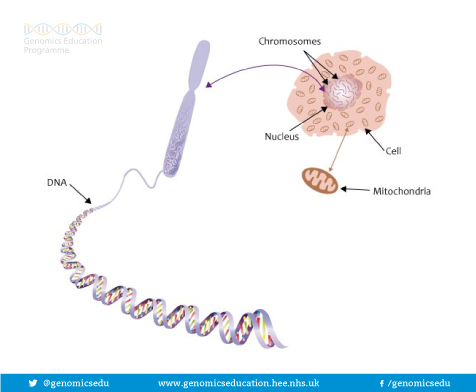

Scientists have also identified some regions in the human genome that correlate with reading ability. However, each of these regions only explains a very small amount of the variation in reading ability between individuals (less than 0.5%). It seems likely that hundreds of small variations in the DNA between individuals account for the inherited component of reading abilities.

Geneticists working on the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) have analysed the DNA from thousands of pairs of twins and they have concluded:

“… there is definitely no single gene for reading ability” 21

Professor Bishop has commented that it is difficult to distinguish between dyslexic people and other poor readers based on biological differences…

“… if you have a diagnosis of dyslexia, this is not an explanation for poor reading; rather it is a way of stating in summary form that your reading difficulties have no obvious explanation.” 20

Since the biological factors involved in dyslexia are complex and not fully understood, the condition is usually diagnosed based on a series of tests and behavioural symptoms (see dyslexia indicators below).

Diagnosing Dyslexia

Some academics argue that we can’t be certain about whether or not someone is dyslexic because there is no universally accepted scientific or legal definition of it.

Different definitions lead to different ways of assessing the condition, so a child might be identified as dyslexic if he or she is assessed according to one definition, but not if they were assessed based on an alternative definition.3

Educationalists and special interest groups often prefer broader, more inclusive definitions because this means more people get recognised as dyslexic and are more likely to get support.

However, there comes a point where a definition can be so broad that almost anyone can fit into it. Indeed, some people have even argued that individuals with normal reading abilities might be dyslexic if they exhibit other symptoms, such as being a bit disorganised for example. 3

Dyslexia Indicators...

When a child undergoes an assessment for dyslexia, they are not just assessed on their reading or spelling ability.

It’s common practice to ask about or look for other symptoms, such as lack of phonological awareness, poor short-term memory, slow processing of information, letter reversals, disorganisation and clumsiness, to name but a few. 3

However, there is no clear agreement about which of these symptoms need to be present before a child is diagnosed as dyslexic. Moreover, some clinicians will describe children as dyslexic even if none of these symptoms are present.

Some assessments also include IQ tests, although it’s not clear why. Most academics agree that dyslexia has nothing to do with basic intelligence. Some dyslexic people have very high IQs and others have average or below average IQs.

Although it’s common to describe some children as dyslexic in spoken conversations, written diagnoses can often be quite vague and might only suggest a child has ‘dyslexic traits’, or ‘shows signs consistent with a specific learning difficulty such as dyslexia’.

Dorothy Bishop, Oxford University Professor of Developmental Neuropsychology says the diagnosis can also depend on which type of professional does the assessing:

“I know of cases where the same child has been diagnosed as having dyslexia, dyspraxia, ADHD, and “autistic spectrum disorder”… , depending on whether their child is seen by a psychologist, an occupational therapist, a paediatrician or a child psychiatrist.” 20

As we mentioned earlier, even one of the most widely accepted indicators of dyslexia, poor phonological awareness, can’t provide a reliable diagnosis of the condition because some children with poor phonological abilities can go on to develop good reading skills. And some children struggle to read even if they have relatively good phonological awareness. The same is true of short-term memory deficits.

To complicate matters further, the symptoms of individual children can change as they get older and some of the symptoms might be displayed by children who can read normally, or by other children with reading difficulties who haven’t had a dyslexia diagnosis.

For example, reversing letters in handwriting is also thought to be an indication of dyslexia. A dyslexic child might write a ‘b’ instead of a ‘d’ or a ‘p’ instead of a ‘q’. However, this problem is actually quite common in many children who are learning to read. Dyslexic children make about the same number of mistakes as children with a similar reading age.22

Professor Frank Vellutino of the University of Albany, New York, asked a group of dyslexic children and normal readers to reproduce Hebrew letters. None of them had seen the Hebrew alphabet before.

Surprisingly, the dyslexic children were able to write the letters as accurately as the normal readers. These results suggested that the dyslexic children could see and interpret the shapes of the letters just as well as normal readers.

Most school teachers aren’t qualified to diagnose dyslexia, although they do usually get some guidance about the symptoms of dyslexia and they might notify parents or special educational needs coordinators in the school if they suspect there is a problem.

However, although schools in the UK can refer children to the local education authority for specialist dyslexia assessments, this doesn’t always happen, and it can take some time. Consequently, many parents choose to have their children assessed privately, which can cost in excess of £600.23

Is It Helpful to Separate Poor Readers Into a Dyslexic Group and a Non-dyslexic Group?

Some academics argue that the extensive assessments done by specialists to assess if children are dyslexic are unnecessary because they are expensive, time-consuming and discriminatory. They say that the costs of these assessments mean there is less funding available to support other struggling readers who don’t get a dyslexia diagnosis.

Geneticist, Robert Plomin has written:

“…there is no simple genetic basis for a diagnosis of a disability called dyslexia. The fact that a child cannot read as well as we would expect is all the evidence that should be required for them to be offered extra support. The money spent on testing and diagnosis – and the time spent waiting for all of this – would be better spent on extra support for all children at the low end of the reading-ability spectrum.” 24

The fact that better-off parents are more likely to raise concerns about their offspring’s reading progress could lead to children from different backgrounds being treated unequally.

Having a diagnosis of a specific learning disorder can have some advantages over just being considered to be a poor reader. And wealthier parents are more likely to pay for private dyslexia assessments.

As well as getting extra time in examinations and perhaps extra support at school, dyslexic students in the UK can also receive grants at university worth several thousand pounds to pay for a learning support tutor and things such as laptops, photocopying, and other materials. 25

Although the British Dyslexia Association claim that dyslexia is independent of socio-economic background,26 there is a great deal of evidence that socio-economic status has a major impact on reading ability:

For example, in a report about education and socioeconomic status, the American Psychological Association quote the following research:

“Children from low-SES families enter high school with average literacy skills five years behind those of high-income students.” 27

And a specially commissioned report in the UK found that around 40% of disadvantaged children are not reading well by the age of 11 – almost double the rate of their better-off peers.28

If a greater proportion of poor children struggle with reading this doesn’t seem consistent with the claim that dyslexia is independent of socio-economic background. Perhaps struggling readers who are poor are less likely to get diagnosed as dyslexic?

It’s possible that teachers or psychologists are more likely to assume that reading difficulties in poor children are caused by their impoverished upbringing, rather than their biology.

While this assumption might be true in some cases, it’s unlikely to be true for all deprived children; research has indicated that it’s difficult to distinguish between neurobiological and environmental causes of reading for individual children.3

Although a dyslexia diagnosis can mean extra support for some children, there may be some disadvantages too.

For example, English teacher, author and teacher trainer David Didau has suggested that being labelled as dyslexic can lead to an attitude of ‘learned helplessness’ in some children. This essentially means that the child assumes there is little point making an effort to improve his or her literacy skills once they find out they are dyslexic. Parents can sometimes have the same attitude.29

However, there are also people who say that a diagnosis of dyslexia can actually empower and motivate some students. They argue that children find it helpful to have some kind of explanation or recognition for their problems.

It’s common to hear people say that being told they were dyslexic meant that no-one could say they were lazy or stupid anymore. However, while this is reassuring for those with a diagnosis, what about struggling readers who are told they aren’t dyslexic? Surely their problems also deserve recognition and they shouldn’t be labelled as lazy or stupid either.

Research conducted by Dr. Simon Biggs has shown that when teachers are provided with a description of a child and told the child has dyslexia, they are less likely to believe that they can do anything to help them improve.

However, if they are presented with a description of the same child, but told they have ‘reading difficulties’, they are more likely to believe they can make a difference.30 This is important because teachers’ beliefs about their potential to help children have been shown to affect academic progress.

Dr. Biggs concluded:

“… we suggest that ‘reading difficulties’ may be a more positively helpful label (if any labels can be helpful) than ‘dyslexia’.

A number of other distinguished academics have expressed similar views…

Professor Frank Vellutino of the University of Albany, New York, has spent years researching literacy development in children and dyslexia. He has long argued that terms such as “dyslexia”, “dyslexics” or “reading disability” should be abandoned in favour of more neutral terminology such as “reading difficulties” or “struggling readers”.3

Keith E. Stanovich, Professor of Applied Psychology and Human Development, University of Toronto has stated:

”The underlying difficulty appears to be the same, the way these children respond to treatment appears to be the same, there appears to be no justification whatsoever for going in and trying to carve out a special group of poor readers.”

“No term has so impeded the scientific study of reading, as well as the public’s understanding of reading disability, as the term dyslexia. The retiring of the word is long overdue.”

Professor Julian Elliot from Durham University and Dr. Simon Biggs from Newcastle University have written:

‘‘… attempts to distinguish between categories of ‘dyslexia’ and ‘poor reader’ or ‘reading disabled’ are scientifically unsupportable, arbitrary and thus potentially discriminatory” 31

After considering evidence from a variety of sources, the UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee were also unconvinced about the benefits of labelling children as dyslexic. They said that definitions of dyslexia were too broad to be useful from an educational point of view and concluded that:

“… ‘specialist dyslexia teachers’ could be renamed ‘specialist literacy difficulty teachers’. There are a range of reasons why people may struggle to learn to read and the Government’s focus on dyslexia risks obscuring the broader problem.” 17 (p28, para. 77)

Yet, in spite of such formidable opposition from prominent scientists and politicians, most people continue to use the terms dyslexia and dyslexic. Some of the above quotes are over a decade old, but there has been no indication that organisations such as the British Dyslexia Association or the International Dyslexia Association are about to change their names.

It seems clear that many parents and children prefer a dyslexia diagnosis compared to a statement that their child is ‘a struggling reader’ or has ‘weak literacy skills’.

When Professor Eliot first publicised his views, there was a sense of outrage from some parents and specialist dyslexia teachers. Getting a dyslexia diagnosis for a child and coming to terms with it can be an emotional rollercoaster for some parents and their children. Removing the dyslexia label might make them feel like something has been taken away from them.

Many people also feel that there is more to being dyslexic than just struggling with reading. As we’ve mentioned previously, a range of other problems have been associated with dyslexia, and some commentators have also suggested that being dyslexic can also have benefits…

Are Dyslexic People Gifted In Other Ways?

The British Dyslexia Association definition for employers makes the following statement:

“Some learners have very well developed creative skills and/or interpersonal skills, others have strong oral skills. Some have no outstanding talents. All have strengths.” 26

We think this statement is a bit too vague to be helpful. It’s a bit like the descriptions that are sometimes found in horoscopes because it could represent almost any group of people in a population.

Opinions about whether or not dyslexic people have special talents seem to be mixed. For example, a group of dyslexic university students and graduates were found to have only average creative and visuo-spatial abilities.3

Other studies have reported superior, inferior, and average levels of visual-spatial abilities associated with dyslexia.32

According to an article published by the International Dyslexia Association, there have been some intriguing studies done into possible advantages associated with dyslexia, but the science is still scant and inconclusive. 33

Researchers in Chile found that college students with good phonological awareness and reading comprehension skills actually performed better on creativity and insight tasks than dyslexic students.34

And when a large sample of adolescents and young adults were assessed for creativity, it was again found that good readers were more creative than dyslexic people.35

However, according to Dr. Guinevere Eden of Georgetown University, there is some evidence dyslexic people are better at seeing differences in visual images that require a focus on the bigger picture rather than small details.36 And dyslexics may have better peripheral vision.37

Another study showed that dyslexic people are faster than average at identifying when images are optical illusions. Apparently, this shows they are better at ‘causal reasoning’. And professional astrophysicists with dyslexia were better at picking out black holes from simulated graphical spectra. 38

However, it isn’t certain whether these differences are due to genetic brain differences or whether they are a consequence of different experiences.

Dyslexic people generally spend less time reading and it’s known that reading changes the wiring of the brain. Years of precise focussing on the details of print enhances certain visual pathways.

Although these brain changes are beneficial for reading there is some evidence that they could have a cost as other neural connections might become less efficient. For example, a group of illiterate adults who were taught to read actually lost some of their ability to process certain types of visual information, such as identifying objects that are mirror images of each other. 38

Other evidence suggests that at least some differences in the way the brain processes visual information might be present in some dyslexic children from birth. A study found that about 60% of children who went on to become poor readers had visual-attention problems when they were in preschool.39

A number of people have suggested that being dyslexic might actually be an advantage in some areas. For example, dyslexia activist Dean Bragonier claims that 35% of all entrepreneurs have dyslexia,40 and there are certainly some notable examples, such as the ‘Virgin’ boss, Sir Richard Branson.

However, it isn’t clear whether this success is due to any special talents that are associated with dyslexia. It might just be that more dyslexic people attempt to start their own businesses because they are more likely to struggle academically and so lack other career options. Perhaps some dyslexic people have a greater determination to prove they can be successful.

According to author Ron Davis, dyslexia is a gift, and for some people, becoming a genius doesn’t occur in spite of being dyslexic, but because of it.41

Although some claims about gifted dyslexic people in various fields are supported by good evidence, others are more difficult to verify. For example, Dean Bragonier claims that 50% of all NASA scientists have dyslexia, but it isn’t clear where he got this information from as we couldn’t find any reference to it on NASA web pages.

Some of the claims about famous people who died a long time ago being dyslexic have also been disputed. For example, although various websites claim that Albert Einstein was dyslexic, other sources suggest that he actually did very well in school and was reading advanced science and philosophy books from a young age.42

Similarly, there is little evidence that Leonardo Da Vinci or Thomas Edison were dyslexic. Some sources say that before Thomas Edison was ten, he had already read History of England, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, History of the World, and The Age of Reason.43

There have also been claims that Walt Disney was dyslexic, but these have been strongly refuted by people working for his family museum.44

Whatever advantages might come with dyslexia, there are certainly some significant drawbacks associated with the condition. Dean Bragonier claims that 50% of all adolescents involved in drug and alcohol rehabilitation have dyslexia and 70% of all juvenile delinquents have dyslexia.40

Around 80% of prisoners in Scotland are functionally illiterate45 and, according to Dyslexia Action, pupils with special educational needs account for 7 out of 10 of all permanent exclusions in UK schools.46 It’s not clear how many of these children are dyslexic but a number of studies have shown that reading problems in school are associated with poor behaviour.47

Annie Murphy Paul articulately summarised some of the potential upsides of dyslexia in her New Your Times article. She concluded her article with the following statement:

“Whatever special abilities dyslexia may bestow, difficulty with reading still imposes a handicap. Glib talk about appreciating dyslexia as a “gift” is unhelpful at best and patronizing at worst. But identifying the distinctive aptitudes of those with dyslexia will permit us to understand this condition more completely, and perhaps orient their education in a direction that not only remediates weaknesses, but builds on strengths.” 48

What Are the Best Treatments for Dyslexia?

One-to-one explicit instruction, with a strong emphasis on phonics has been shown to make the biggest difference to the reading abilities of children diagnosed with dyslexia.3, 49

Other alternative approaches, such as visual, auditory and motor training activities, tinted lenses and fish oil supplements have been promoted in the past. However, there is little scientific evidence that these alternative treatments are effective.3, 50

Some promoters of alternative methods do cite research studies, but these need to be evaluated carefully.

For example, one alternative method involves making clay models of words. A site endorsing the method does provide a research list, but it’s mainly a collection of very small studies; some involving only 1 or 2 students.

Several of these studies have no control groups, and in the ones that do it’s not always clear what type of instruction the control students received. Some of the studies didn’t even assess improvements in literacy and many of the studies were carried out in non-English speaking countries.

We accessed the full paper for one of the studies and the results were hardly impressive:

Four students had eight hours of one-on-one tutoring. This involved making clay models to improve their spelling of just 8 words. At the end of the study, three of the four participants could spell just one extra word correctly and one student’s spelling actually got worse! None of the students could spell more than half of the words correctly at the end of the study.

This seems to be incredibly slow progress after 8 hours of one-to-one tuition, yet the website presents a short description of the study as evidence for the effectiveness of the method.

Many dyslexia groups promote reading programmes based on something called the ‘Orton-Gillingham’ (O-G) multisensory approach. However, some researchers and specialist reading teachers claim that the O-G approach is rather outdated and includes some practices that have little benefit and others that could even be detrimental to the effective teaching of reading.51

Even the International Dyslexia Association has admitted that there is a lack of quality research to confirm the effectiveness of the Orton-Gillingham approach.52

The UK House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (2009) invited experts from all sides of the dyslexia debate to provide evidence and express their opinions about effective reading interventions. They concluded:

“… the techniques to teach a child diagnosed with dyslexia to read are exactly the same as the techniques used to teach any other struggling reader. ….There is little evidence to support the use of any special approaches for dyslexia…” 3

When some children fail to pick up reading as quickly as their peers, it’s not uncommon to hear teachers say that phonics hasn’t worked for them, so they might need a different type of reading instruction. Or it might be argued that the child has a different learning style that doesn’t suit phonics.

But these arguments are quite flawed, as Gordon Askew Pointed out in his blog article53 and we discuss in our article about objections to phonics.

Even when teachers do a good job delivering phonics instruction to a class, there are a variety of reasons why a few children might not grasp it very well.

For example, they might have been absent or feeling ill during some key lessons, they might be struggling with undiagnosed hearing problems, they might just be a bit slower at picking up the ideas, they might be getting very little support at home or they might suffer from anxiety or social issues.

If children are struggling to decode written words, abandoning or reducing the amount of phonics instruction is likely to be counterproductive.

The idea that letters represent spoken sounds is essential knowledge because it’s the foundation of our alphabetic writing system. Phonics instruction teaches this knowledge and learning to read without it is like trying to do advanced mathematics without learning what written numbers represent.

If a child was struggling with simple calculations it would be crazy to abandon the instruction of basic number skills and it’s the same with reading and phonics instruction. Children who haven’t grasped the basic alphabetic code might just need to have it explained more clearly, more slowly, more skilfully or more often until they get it.

To use another analogy, if someone wants to learn chemistry, they need to understand that the symbols in the periodic table represent elements and that these elements can combine together in different ways to make a vast number of compounds. So elements are a bit like letters of the alphabet and compounds are a bit like words.

There’s a lot more to chemistry than learning about elements in the periodic table, but without this essential knowledge a student would struggle to understand what formulae and equations represent and many other topics in the subject would be inaccessible.

Similarly, there’s more to reading than decoding words using phonics; children also need to understand what they are reading and they should get some enjoyment from it. However, comprehending a piece of writing and getting pleasure from it is much more difficult for children if they can’t decode most of the words. It’s also very difficult to spell words accurately without a basic understanding of phonics.

Another common response to a dyslexia diagnosis is to provide the child with a word processor so they don’t have to write by hand. Some dyslexia organisations encourage children to start using word processors as soon as reading difficulties have been identified. We know of parents who have been told they should pay for their children to attend weekly typing lessons immediately after a dyslexia assessment.

However, while word processing skills might benefit some children in the long-term, it would seem more appropriate to focus on intensive writing instruction first since there is evidence that this is more likely to improve their spelling and reading skills than typing.54

Can Dyslexia be Cured?

This depends on how you define dyslexia really. For dyslexic children who have a broader range of problems, they might always need support with some of their difficulties.

However, if we think of dyslexia as primarily a reading difficulty, there is evidence that many children who have been diagnosed as dyslexic can overcome this problem and go on to achieve academic success…

According to the International Dyslexia Association, most dyslexic people can be taught to read.55 However, this does require intensive, structured and prolonged literacy instruction with a focus on phonics.

Dyslexia researcher and neuroscientist Dr. Gordon Sherman has written:

“… effective early instruction can prevent and diminish reading disabilities in children with dyslexia and forestall associated academic problems.” 18

A Carnegie Mellon University brain imaging study showed that the brains of dyslexic students appeared to permanently rewire themselves after 100 hours of intensive reading instruction.56

At the one-year follow-up scan, the activation differences between good and poor readers had nearly vanished, suggesting that the neural gains were strengthened over time, probably due to engagement in reading activities.

Similar changes in brain activation have been documented when dyslexic children have been given specialised spelling instruction.57

Some dyslexic children can make really dramatic improvements in their reading ability. For example, an eight-year-old boy was reading at the bottom 10% for his age group and his brain imaging scan showed brain activation patterns that are typical for dyslexic people.

However, after a year’s intensive phonics instruction, his decoding ability was better than average and his reading comprehension had increased from the tenth to the 85th percentile. 58

You can see a short video outlining the boy’s journey below…

This video clip from the BBC documentary Brain Story has a similar success story. The joy on the boy’s face when he realises he has changed his brain could be very motivating for a child in a similar position. View from around 17.5 minutes.

There’s evidence that if a child is having problems it’s better to start some kind of intervention as soon as possible; interventions with older children are often less successful.3, 59 This is partly because children become increasingly frustrated the longer the problem persists, so they are more likely to develop a negative emotional response to reading practice.

Specialist reading tutor Susan Godsland provides the following advice on her dyslexics.org.uk website:

“It is absolutely essential that the school implements some one-to-one tutoring immediately it is noticed that the child is failing to keep up with his/her classroom companions and that the tutor uses more of the same synthetic phonics programme, or an intervention programme based on the synthetic phonics principles.” 60

A small proportion of children continue to experience significant difficulties in reading even after structured interventions. However, as we mentioned earlier, some schools use ineffective methods for their interventions. Also, the amount of instruction that children are likely to receive during school interventions might not be sufficient.

For example, in one successful academic study, children with dyslexia had instruction for two hours a day for eight weeks followed by one hour a day for another eight weeks. Few schools are likely to provide anywhere near this amount of support for struggling readers.61

When schools do provide intensive and prolonged phonics instruction, there’s evidence that even serious reading difficulties that have persisted during primary school can be overcome.

For example, a school in a deprived area of London has made dramatic improvements in children’s reading ages with 4 hours per week of dedicated phonics instruction along with extra reading practice.62

So it appears that some dyslexic children may have to work very intensively before they are likely to overcome their difficulties. But it’s also clear that many dyslexics can become reasonably proficient at reading to the point where they no longer have a significant disadvantage in their wider education.

For those who still struggle to read, other types of support such as reading and voice recognition technology can be helpful.

There is also evidence that adults with dyslexia can make significant improvements in their reading ability if they receive intensive instruction.63

In one study, a group of adults received phonics-based instruction for fifteen hours a week for eight weeks. According to the senior researcher, the gains in reading ability were significant enough to make a difference in the everyday lives of participants. And brain imaging showed that the participants had increased activity in the areas of the brain associated with skilful reading. This shows that even adult brains are capable of ‘rewiring’

Click here if you want to review the summary of this article or see below for more information about dyslexia help for kids.

Further Information…

International Dyslexia Association: https://dyslexiaida.org/

British Dyslexia Association: http://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/

Susan Godslands Dyslexics.org.uk contains a wealth of information and links to articles about reading difficulties and dyslexia.

Click on the following link if you would like to know more about teaching phonics.

Click on this link if you would like more information about helping your child improve their spelling using phonics.

If you would like to improve your child’s writing skills, see our article ‘How to Teach Handwriting’.

References:

- Hornby, G. Atkinson, M. Howard, J. (2013), Controversial Issues in Special Education, Routledge.

- British Dyslexia Association: https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/dyslexic/dyslexia-and-specific-difficulties-overview

- Elliott, J. and Grigorenko, E. (2014), The Dyslexia Debate, Cambridge University Press.

- Godsland, S. Room 101. Dyslexics.org.uk

- Early Literacy Interventions – Science and Technology Committee (Dec. 2009): https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmsctech/44/4405.htm

- BBC News, Education and Family, Pupils’ real classroom behaviour caught on camera, Classroom secrets, BBC One (July 2011): http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-14139555 Also, Pivotal Education, Paul Dix on Breakfast (July 2011): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2DZHJTrG1N4

- Early Literacy Development, Reading Rockets: http://www.readingrockets.org/reading-topics/early-literacy-development

- THE BRAINS CHALLENGE, CHILDREN OF THE CODE: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/index.htm

- Dyslexia, Episode 3 of 3, Growing Children, BBC 4 (August 2012)

- Dyslexia not linked to eyesight, says study, BBC News, Education and Family (May 2015): http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-32836733

- Dyslexia link to eye spots confusing brain, say scientists: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-41666320

- Franceschini, S. et al. (2012) A Causal Link between Visual Spatial Attention and Reading Acquisition, Current Biology: http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(12)00270-9

- Willingham, D. (2014), When educational neuroscience works! The case of reading disability: http://www.danielwillingham.com/daniel-willingham-science-and-education-blog/when-educational-neuroscience-works-the-case-of-reading-disability

- Dyslexia Study In Science Highlights The Impact Of English, French, And Italian Writing Systems: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/03/010316073551.htm

- What is Dyslexia? Dyslexics.org.uk

- Godsland, S., Myth 16, Dyslexia Myths and Facts.

- House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Evidence Check 1: Early Literacy Interventions, Second Report of Session 2009–10, Paragraph 84: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmsctech/44/44.pdf

- org: http://impactofspecialneeds.weebly.com/uploads/3/4/1/9/3419723/brain_research_and_reading.pdf

- Fields, D. Watching the Brain Learn, Scientific American, Nov.2009: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/watching-the-brain-learn/

- What’s in a name? (Dec. 2010), BishopBlog: http://deevybee.blogspot.com/2010/12/whats-in-name.html

- A2 Science in Society (2009), Heinemann

- The Dyslexia Myth’ (2005), Channel 4 TV Production: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6lrAQedApVg

- Diagnostic Assessments, British Dyslexia Association (Nov. 2017): http://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/services/assessments

- Asbury, K. and Plomin, R. (2013) G is for Genes, The Impact of Genetics on Education and Achievement, Wiley, See also ‘The Dyslexia Myth’ (2005), Channel 4 TV Production.

- What learning support can you get at university if you have dyslexia? Which University (2016): https://university.which.co.uk/advice/student-finance/what-learning-support-am-i-entitled-to-if-i-have-dyslexia

- British Dyslexia Association, Definitions, definition for employers, accessed 2018.

- Education and Socioeconomic Status, APA: http://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/education.aspx

- Poor reading ‘could cost UK £32bn in growth by 2025’, The Guardian (Sept. 2014): https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/sep/08/reading-literacy-uk-cbi-schools-read-on-get-on-campaign

- Does Dyslexia Exist? The Learning Spy (2013): http://www.learningspy.co.uk/featured/does-dyslexia-exist/

- Gibbs, S. (2015), Labelling children dyslexic could hinder teachers, BERA: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/labelling-children-dyslexic-could-hinder-teachers

- Elliott, J.G. & Gibbs, S. (2008). Does dyslexia exist? Journal of Philosophy of Education 42(3-4): 475-491: https://www.dur.ac.uk/education/staff/profile/?mode=pdetail&id=2004&sid=2004&pdetail=63490

- Gilger et al. Reading disability and enhanced dynamic spatial reasoning: A review of the literature, Science Direct: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278262616300227

- Cowen, C. and Sherman G. (2012) Upside of Dyslexia? Science Scant, but Intriguing, International Dyslexia Association: https://dyslexiaida.org/upside-of-dyslexia/ (last accessed March 2018).

- Reading Skills, Creativity, and Insight: Exploring the Connections, The Spanish Journal of Psychology, Volume 17 (2014): https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/spanish-journal-of-psychology/article/reading-skills-creativity-and-insight-exploring-the-connections/FFE2FF6477EB81B0C4C05008B85E4FC5

- The relationship of reading ability to creativity: Positive, not negative associations, Science Direct: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104160801300040X

- Dyslexia and the Brain (2016) Understood: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrF6m1mRsCQ

- Rodriguez, J (2012) Research Into Dyslexia Reveals Special Gifts and Talents: http://www.care2.com/causes/research-into-dyslexia-reveals-special-gifts-and-talents.html

- Schneps, M (2014) The Advantages of Dyslexia, Scientific American: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-advantages-of-dyslexia/

- Franceschini, S. et al. (2012) A Causal Link between Visual Spatial Attention and Reading Acquisition, Current Biology: http://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(12)00270-9

- The True Gifts of a Dyslexic Mind | Dean Bragonier | TEDxMarthasVineyard: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_dPyzFFcG7A

- Davis, R. (1997), The Gift of Dyslexia: Why Some of the Brightest People Can’t Read and How They Can Learn, Souvenir Press Lt.

- Einstein’s Learning Disability, A to Z of Brain, Mind and Learning: learninginfo.org/einstein-learning-disability.htm

- Famous People With Dyslexia: Were Einstein, Da Vinci and Edison Dyslexic?, A to Z of Brain, Mind and Learning: http://dyslexia.learninginfo.org/famous-people.htm

- Famous People With Dyslexia: Walt Disney and More…, A to Z of Brain, Mind and Learning: http://dyslexia.learninginfo.org/famous-people2.htm

- Most Scottish prison inmates ‘have poor reading skills’, BBC News (Dec. 2012): http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-20852685

- Facts and figures about dyslexia, Dyslexia Action: http://www.dyslexiaaction.org.uk/page/facts-and-figures-about-dyslexia-0#_edn6

- Literacy and Behaviour, National Institute for Direct Instruction (2016).

- The Upside of Dyslexia, New York Times (Feb. 2012): http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/05/opinion/sunday/the-upside-of-dyslexia.html?_r=3

- Room 101, dyslexics.org.uk

- Wilson, C. Forget colour overlays – dyslexia is not a vision problem. New Scientist, May 2015: https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn27588-forget-colour-overlays-dyslexia-is-not-a-vision-problem/

- Godsland, S. Specialist dyslexia teaching and programmes / Orton-Gillingham. Room 101.

- Orton-Gillingham: It’s Complicated – Part I, Neuro-Development of Words – NOW!: http://www.nowprograms.com/orton-gillingham-its-complicated-part-i/

- And now for something completely different (Dec. 2014) SSphonix (no longer available).

- 5 Brain-Based Reasons to Teach Handwriting in School. Psychology Today

- Frequently Asked Questions, International Dyslexia Association (Nov. 2017): https://dyslexiaida.org/frequently-asked-questions-2/

- Remedial Instruction Rewires Dyslexic Brains, Provides Lasting Results, Study Shows, Science Daily (August 2008): http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/08/080805124056.htm

- Brain Images Show Individual Dyslexic Children Respond To Spelling Treatment, Science Daily (Feb. 2006): https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/02/060208162228.htm

- ‘Rewiring the Brain’ Video 2/7 Reading and the Brain, Reading Rockets: http://www.readingrockets.org/shows/launching/brain

- Waiting Rarely Works: Late Bloomers Usually Just Wilt, published in the American Educator 2004.

- Should I have my child assessed? or Why isn’t my child learning to read? Dyslexics.org.uk.

- May, T. Dissecting Dyslexia, Reading Rockets (Nov. 2017): http://www.readingrockets.org/article/dissecting-dyslexia

- Birbalsingh, K. et al. (2016) Battle Hymn of the Tiger Teachers, The Michaela Way, John Catt Educational Ltd.

- Adults With Dyslexia Can Improve With Phonics-based Instruction, Research Shows, Science Daily (October 2004): https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2004/10/041027144140.htm