Learn about the most effective reading comprehension strategies that you can use with your child at home…

In our previous article, Reading Comprehension Basics, we mentioned some of the essential skills children need to be able to comprehend written English.

Although that article was mainly concerned with improving the comprehension of beginning readers, much of the content is also relevant for independent readers. Consequently, you might find it helpful to read it first before continuing with this article.

All of the strategies in this article have been shown to be effective ways of improving kids’ reading comprehension in classroom studies. And each of the strategies can be used by parents who want to help their children at home.

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Disclaimer: We support the upkeep of this site with advertisements and affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you click on the ads or links or make a purchase. There is no additional cost to you if you choose to do this.

Contents:

Summary

- Continue reading with your child even when they can do it independently. Discuss the characters and storylines with your child and explain the meaning of new words they encounter.

- Use some specific comprehension strategies occasionally, but don’t overuse these or they could make reading sessions feel like a chore for you and your child.

- Specific comprehension strategies can be categorised into different phases as described below, but you don’t need to stick to these too rigidly or feel you need to use a strategy during every phase.

Strategies discussed in this article for each phase include:

Orientation Phase…

Strategies to get your child into the right frame of mind prior to reading the text so they get the most out of the experience:

- Preview / Overview

- Discuss Relevance / Importance or Why it Might be of Interest.

- Activate Prior Knowledge

- Predicting

Active Reading Phase…

Encouraging your child to think and monitor their comprehension while they are actually reading:

- Questioning and Clarifying

- Making Inferences

- Visualizing

Review Phase …

Helping your child to think more deeply about the content after reading:

- Summarisation

- Identifying the Structures of Texts

- Compare and Contrast (Similarities and Differences)

Does My Child Need Help With Their Comprehension Once They Can Read Independently?

A child’s comprehension should continue to improve without a lot of assistance once he or she starts to read independently. However, children can still benefit from some support at this stage, so it’s important to continue reading with your child regularly.

Children gradually absorb more grammatical rules from texts as they read more widely and they can pick up the meaning of a variety of new words when they are reading by making inferences from the context.

Nevertheless, they are still likely to encounter some challenging vocabulary that they can’t figure out themselves, so it does help if there is an adult around to explain any unfamiliar words in a piece of text.

Explaining vocabulary to a child can be tricky because we often use synonyms to explain words, and children might not know the meaning of the synonyms we use.

It can sometimes be difficult to think up an explanation for the meaning of a new word on-the-spot, so having a children’s dictionary nearby can be helpful since these are written to be more appropriate for the limited vocabulary of a child.

In an ideal world, you could look up potentially tricky vocabulary in a book before you read with your child and prepare explanations for them in advance. However, it can be difficult to find the time to do this once your child gets onto longer books.

If you think your child might need to expand his or her vocabulary there are ways of teaching it more directly, and we’ve included information about this in a separate article.

Another important reason to continue reading with your child is because you can help them get more pleasure from reading when they start doing the more challenging chapter books.

This can be a difficult transition for children and the more support they get at this time the more likely they are to stay motivated to continue reading in the future.

Take turns reading different pages or paragraphs out loud with your child. It’s really good for them to hear an adult reading with expression, rhythm and intonation, and it can be fun trying to do different voices for the characters.

Plus, if you’re reading a book together you can discuss it together afterwards, both to help with comprehension and just for the pleasure of having a conversation together.

You could ask them to summarise what you read the previous day before you start a new chapter (say that you’ve forgotten what happened).

Even when your child is reading more fluently and independently, you can still ask them similar questions to the ones we mentioned in part 1 in the section about how to get the most out of reading to your child. For example:

What do you think of the different characters? Who is your favourite and why? Why do you think that Fred is so mean? What was the reason that Jenny got upset? How would you feel if that happened to you? What do you think Billy meant when he said …….? What do you think might happen in the next chapter? How might the story end? And so on.

As your child gets more advanced you could also discuss things like the writing style and the different adjectives the author used in a passage etc.

Remember not to overdo the questions though, use them sparingly and keep it low-key so your child doesn’t feel anxious about your reading sessions; you want them to be enthusiastic about spending this intimate, quality time together.

If you both look forward to reading together then you’ve probably got it about right. But if one of you feels like it’s becoming a bit of a chore you need to back off the questions and put more effort into bringing the books alive.

Specific Comprehension Strategies …

According to Professor Dan Willingham, a Cognitive Neuroscientist, it’s not worth spending a huge amount of time teaching reading comprehension. He has written:

“acquiring a broad vocabulary and a rich base of background knowledge will yield more substantial and longer-term benefits”. 1

Nevertheless, Professor Willingham agrees that spending some time teaching reading comprehension strategies can be beneficial.

The following strategies are things which are sometimes used by teachers in schools and they’ve all been subjected to classroom studies which have shown them to be effective.2

There are a variety of other strategies that could be effective, but some of them are more suitable for group work in a classroom and the ones below have the strongest evidence that they improve comprehension.

As we’ve already stated, it’s important not to overdo things. A school teacher wouldn’t try to employ all of these strategies during every classroom reading activity and nor should you.

The last thing you want to do is to spoil the flow of a good story and make your child feel like he or she is being cross-examined every time they pick up a book.

So use these strategies occasionally over the course of a number of weeks, rather than every session.

Some of the suggestions that follow won’t be relevant to every type of book, and some might need to be adapted to suit your child’s age and stage of development, so don’t be afraid to improvise.

The important thing is to get a flavour of the sort of things you can do or ask when the opportunity arises.

If you try to work rigidly from a script you could spoil the experience of sharing a book together by making it too formal.

Whatever strategy you use, remember that the main aim is to get your child to monitor their own comprehension by thinking about what is happening in a story or factual book when they are reading.

You will notice that some of the suggested questions we outline below are similar to the ones we’ve already mentioned; we’ve just presented them in a more structured way here.

It can be convenient to categorise the comprehension strategies into different phases as we’ve done below, but you don’t need to stick to these too rigidly or feel you need to be using a strategy during every phase.

Strategies for the Orientation Phase

These strategies help to get your child into the right frame of mind prior to reading a book so they get the most out of the experience. They include:

- Preview / Overview

- Discuss Relevance / Importance or Why it Might be of Interest.

- Activate Prior Knowledge

- Predicting

Preview / Overview …

First, help your child to get an overview of the information to be studied. Overviews can be helpful for all sorts of activities, not just reading, because they provide us with a general context that helps us make sense of individual details when we encounter new information.

For example, if you are doing a jigsaw it helps to look at the picture on the box before you inspect the individual pieces and try to put them together.

If you plan to watch a new drama or film on TV it can help you make more sense of the story if you’ve checked out the description of the film in a TV guide first, and it’s similar when we encounter new material in a book.

For fiction books, the preview/overview might be as simple as reading the synopsis on the back cover and having a look at some of the illustrations and chapter headings.

With non-fiction, it can help to skim read the chapter to be studied, focussing on the main points and headings before you get into the details. Previewing a chapter like this gives students an idea about the basic structure and content before they get into the details.

Discuss Relevance / Importance or Why it Might be of Interest

The more enthusiastic you can make your child about a book before they start to read it, the more likely they are to engage with the content.

So it can help to explain why you chose a particular novel to read with your son or daughter – perhaps you read it yourself as a child, it’s been recommended by a friend or it’s had great reviews.

For non-fiction texts try to explain why the information might be relevant or interesting:

- “This book’s going to explain why it gets dark at night”

- “We’re going to learn about something called electricity that makes the TV, lights and computer work”,

- “We’re going to find out about some things that happened a long time ago that made living in our country a lot better for people like us”,

- “We’re going to learn about some interesting people and amazing animals that live in a place on the other side of the world”

- “If we look at some of the stuff in this book now, you’ll be able to answer loads of questions in class and that will really impress your teacher.”

Activate Prior Knowledge …

When we’re learning something new, our brains try to make sense of the information by linking it to things we already know and understand.

So if you’re looking at a book that has a similar theme to something your child has already encountered, it can help to remind them of any common ideas.

This makes it easier for them to link ideas in the new text to information they already know. For example:

“This book is about a boy who lived a long time ago and started off living in an orphanage. Remember we read ……… a while ago and it mentioned someone living in an orphanage. Can you remember what an orphanage is and what they were like in the olden days?”

“This book is about the Viking Gods. Do you remember when we read about the Romans and Egyptians? They had Gods too. Do you remember any of them and what they were in charge of?”….”Well some of the Viking Gods were in charge of different things too, for example, there’s a really famous one called Thor…”

“Do you remember we read something about things called germs a while ago, can you remember what these are and what they can do to us?” …”Well, this book’s about a famous man who found a way to stop people from getting ill from some really bad germs.”

Predicting …

At the simplest level, this might involve looking at the title and cover illustrations and asking your child whether a book might be of interest to them and why.

After reading a few passages which might introduce the main characters, you could then ask them to predict something about each character:

Which characters are most likely to get into some kind of trouble? Who might be the ones who will sort any problems out and be the hero or heroine? Which ones are likely to be ‘goodies’ and which ones might be ‘baddies’?

Ask them to develop their answers further by explaining their opinions: ‘Why do you think that?’

As you progress through the book, see if your child can predict what might happen in the next chapter or at the end of the story.

Strategies for the Active Reading Phase

These strategies encourage your child to think and monitor their comprehension while they are actually reading. They include:

- Questioning and Clarifying

- Making Inferences

- Visualizing

Questioning and Clarifying …

This is about encouraging your child to ask questions of their own when they encounter things they don’t understand. These might be unfamiliar words or things to do with the storyline.

If your child really isn’t sure about something then help them, but also try to show them how they can find out some answers for themselves.

Get them into the habit of looking up unfamiliar words in a dictionary. They should also be encouraged to look back in a book to find information that’s needed to clarify anything they aren’t sure about.

Try not to criticise your child if they ask you a question that seems too simple.

Making Inferences …

It’s important that children are aware of the importance of making inferences so they can understand passages when information isn’t directly stated.

Explain to your child that sometimes the story doesn’t include every detail because otherwise, it would be too long or boring.

So instead, the author might give you a few clues that help you guess or figure out the missing bits.

Other times, the author might just expect you to figure stuff out based on what you already know from your own experiences.

For example, imagine a story about a girl in a school canteen:

“Jenny’s plate slid from her tray and smashed on the floor; she went bright red.”

You could ask your child to explain why the student went bright red; perhaps by asking her how other students might react if they heard a plate smashing and how she might feel if she dropped a plate.

Or, in another story:

“Billy’s Mum said he should take his coat when he set off to his friend’s house, but he didn’t think he needed to. However, on the way home, he wished he had listened to his Mum.”

Ask your child why they think Billy ignored his Mum’s advice and why he wished he had listened to her when he was on his way home.

In our previous comprehension article, we mentioned that it can be very difficult to make inferences without having the relevant background knowledge. It’s important to remember this point so you don’t keep pressing your child about something that seems obvious to you.

If you’ve given a few prompts, and your child still can’t make sense of it then a lack of background knowledge might be the problem.

If this does seem to be the case then just use it as an opportunity to discuss the facts they need to know. You might recall the campfire example from our previous article.

‘The campfire started to burn uncontrollably. Tom grabbed a bucket of water.’

In this case, they need to know that a campfire out of control could burn a tent down or even spread and start a forest fire.

They also need to know that a bucket of water could put a small fire out before it spreads and causes serious damage.

There’s a good article here about teaching younger children about making inferences and drawing conclusions on the Reading Rockets website.

And this short video by Vanessa Miller provides useful information about Making Inferences:

Visualising …

When we read we often create mental images of the things described in the text. These images help us to interpret the information we are reading, thereby improving our comprehension.

Many people visualise information naturally without any instruction, but research has shown that some children can benefit from being shown how to do this by an adult.

First, read a descriptive sentence or passage to your child and then describe your interpretation of it to them.

This might include information of what the setting looks like or the appearance of the characters. Explain how the words in the text helped you to come up with your visualisation.

You should also explain that visualisation often involves using our imagination because authors can’t possibly include every detail; otherwise, their books would be too long.

Also mention that you can include actions, smells and feelings as well as visual images when you create an image in your mind.

Get your child to practise visualising and describing some descriptive passages and compare them to your own interpretations.

If they are different try to explain why this might be. Is it because you imagined things differently or did you interpret what the author said in different ways?

Strategies for the Review Phase

These strategies help your child to think more deeply about the content after reading. They include:

- Summarisation

- Identifying the Structures of Texts

- Compare and Contrast (Similarities and Differences)

Summarisation…

Asking your child to summarise a chapter they’ve just read can help them to remember the information more clearly and make more sense of it. This will help them to get more out of subsequent chapters.

You could ask your child to summarise a chapter just after you have read it, or the next day before you read a new chapter.

If you find your child struggles to do this, skim through the chapter again with them, picking out the main characters and ideas and maybe jotting them down.

It can also help if you give your child some simple prompts like ‘who was the chapter about and what happened to them?’

Some of the prompts for identifying the structures of texts (described below) can also help with summarising.

Identifying the Structures of Texts …

When children are taught to recognise the way stories or non-fiction texts are structured this can help them to connect and classify different bits of information.

Consequently, they are more likely to understand and remember what they read.

Narrative Texts:

Most story structures contain a number of similar features, and we’ve outlined some of these below.

However, it’s also important to point out that different stories don’t always have identical features and that different authors can introduce aspects of their stories in alternative orders.

We’ve included some questions below that you can use as prompts when you are discussing the structure of a story with your child:

- The Characters: Who is the story about? What are the different characters like – big, small, ugly, pretty, handsome, scary, cute, good, bad, kind, silly, brave? Who are the most important characters in the story?

- The Setting: Where did the story take place? What is the place like? Is there more than one setting? When did the story happen?

- The Introduction/ Beginning: What were the different characters doing or trying to do at the start of the story? What did they want and why?

- The Problem/Conflict: Does anything happen that makes it more difficult for the characters to get what they want? What goes wrong? Is it a mystery? Does anyone argue or fall out? Why?

- The Resolution: How do the characters solve the problem or mystery? Does anyone help?

- The Ending: What happens to the characters after everything is sorted out? Is it a happy or sad ending? Does anything happen that might lead to the author writing another story about the characters?

- The Moral or Purpose of the Story: Did the author write the story to excite you, scare you or to make you laugh? Did they have a lesson they wanted you to learn from the story?

Examples might include: It’s wrong to judge people by their appearance. Always treat people kindly. Follow your parents’ instructions if you want to stay safe. Don’t tell lies. Strangers might not be telling you the truth etc.

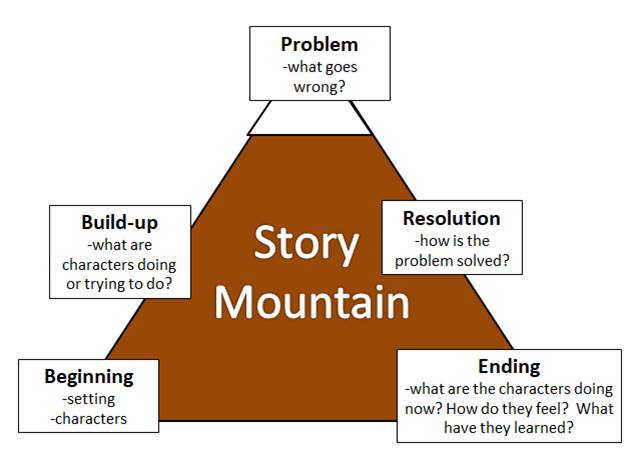

Graphic organisers are templates or diagrams that can be used to provide visual prompts for the various features in a story structure.

Examples of graphic organisers you might find useful include story maps and story mountains. Templates like these can be useful to help students plan stories as well as interpret them.

Non-fiction Books

Help your child to recognise that non-fiction books usually have different structures to stories.

Explain that the information is usually divided into different sections called chapters that focus on particular topics and discuss the importance of headings and sub-headings within the chapters.

You could also talk about the fact that non-fiction books often contain descriptions or explanations and you could discuss things such as how explanations might include a sequence of events or how one thing causes another.

Although it might seem obvious to experienced readers, even some secondary school children seem to be unaware of the usefulness of contents and index pages. Show your child how they can use these pages to look up information.

Compare and Contrast (Similarities and Differences)…

Getting children to think about how a book or topic is similar to something they have met before and then identifying specific differences helps them to develop a deeper understanding of the material.

This could be as simple as comparing and contrasting characters and plots in different fairy tales.

With young children, this doesn’t need to be done too comprehensively, but even with a short discussion and a bit of prompting, children can identify similarities in story structures: selfish villains, vulnerable characters who suffer unfair treatment and brave/kind people who help them out.

Once they’ve identified similarities, thinking about differences makes children process the material even more deeply.

And once they’ve been through the experience a couple of times, children start to recognise the story structures in new books more quickly, which helps them get a better grasp of the plot.

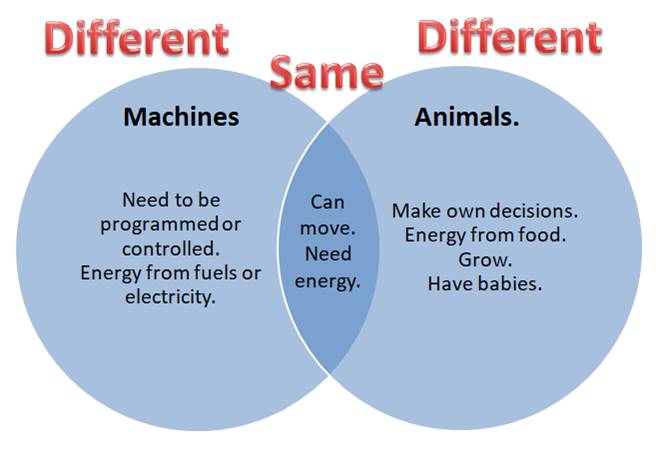

Children can also be taught to compare and contrast ideas in non-fiction.

For example, after reading a book about animals in the sea, you could discuss similarities and differences between whales and fish.

The same idea can be used to compare just about anything – plants and animals, machines and living things, dogs and cats, historical events, countries or even adjectives and adverbs.

It can help if you jot some of the ideas down, and Venn diagrams can be especially useful for making comparisons:

It can also be helpful to provide your child with criteria for some of the comparisons.

For example, with whales and fish you could talk about body parts, how they breathe, where they live, how they move about, what their skin is like and whether they lay eggs or have babies.

With two different countries, you could compare things like climates, plants and animals, natural resources, population and lifestyle/standard of living.

Analogies can be another useful way of comparing and explaining things. Common examples include comparing a battery in an electric circuit to a water pump and comparing white blood cells to guards or soldiers.

It’s difficult to think up good analogies for every subject but you can probably find some useful examples by doing a quick Google search.

Finally

The ideas we outlined in our previous article build the foundations of good comprehension skills.

The strategies outlined in this article can also be helpful, but be selective and take care not to overuse them. Even the best strategies could detract from your child’s enjoyment of reading if you use them excessively.

The more enthusiasm your child has for reading the more they will want to do it, and, ultimately, the volume of books they read over a period of time will have the greatest impact on their comprehension skills.

See below for other useful links.

Further Information…

Click on the following link if you would like more information about improving your child’s vocabulary.

If you would like more information about teaching your child to spell then click on this link: ‘How to Teach Spelling Using Phonics.’

If you would like more information about the different approaches to teaching children to read, see our article: ‘How Can I Teach My Child to Read?’

If you would like to know more about teaching your child phonics, see our article “How to Teach Your Child Phonics”.

References:

- ‘The Usefulness of Brief Instruction in Reading Comprehension Strategies’ by Dan Willingham, American Educator, Winter 2006/07

- Review by the US National Reading Panel (2000).

Marzano, R (2001), Classroom instruction that works, ADCD,

Petty, G (2006), Evidence Based Teaching, Nelson Thornes

Institute of Educational Sciences Practice Guide (2010), Improving Reading Comprehension