This article will give you a greater awareness of the hurdles children face when they are learning to read – and how you can help them.

When children are learning to read it can be a frustrating time for some parents and an anxious time for their children. But when parents understand more fully what reading involves and why their children find it difficult, they can be more sympathetic and patient with them.

Learning to read involves the development of a range of complex skills that many adults aren’t fully aware of…

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Contents:

- Why Reading Is Difficult

- Similar Shape, Different Meaning

- Learning to Read in English Is Harder Than Learning to Read in Many Other Languages

- Reading Taxes the Brain

- Why Some Parents Get Frustrated With Their Children

- Why Your Reactions to Your Child’s Difficulties Matter

- How Should I React?

- Conclusion

- Further Information

- References

Summary…

- Our alphabet and the thousands of words made up by it are a set of coded instructions about spoken language. When we write, we’re actually drawing sounds using letters, which are symbols for the sounds. And when we read we’re decoding these symbols.

- There are more sounds in the English language than there are letters in the alphabet. The shortage of letters in our alphabet means we have to use combinations of letters to represent some sounds. This, and other complications with our spelling system, makes learning to read in English more difficult than for many other languages.

- Learning to read involves much more than memorising a few isolated bits of information about letters. When we read, our brains have to simulate speaking and listening through complex visual, cognitive and auditory interactions.

- Your child has to learn to process text automatically before they can fully appreciate a piece of writing. This requires a great deal of concentrated effort and practice.

- Children can get anxious or embarrassed when they make mistakes, especially if they are criticised for them.

- Your child will experience less anxiety and make faster progress if you are supportive and understanding.

Why Reading Is Difficult

It’s easier to appreciate why learning to read is difficult for some children when you consider what written words really are…

Our alphabet and the thousands of words made up by it are a set of coded instructions about spoken language. When we teach a child to read we are essentially helping them to decipher a complex artificial code made up from abstract symbols.

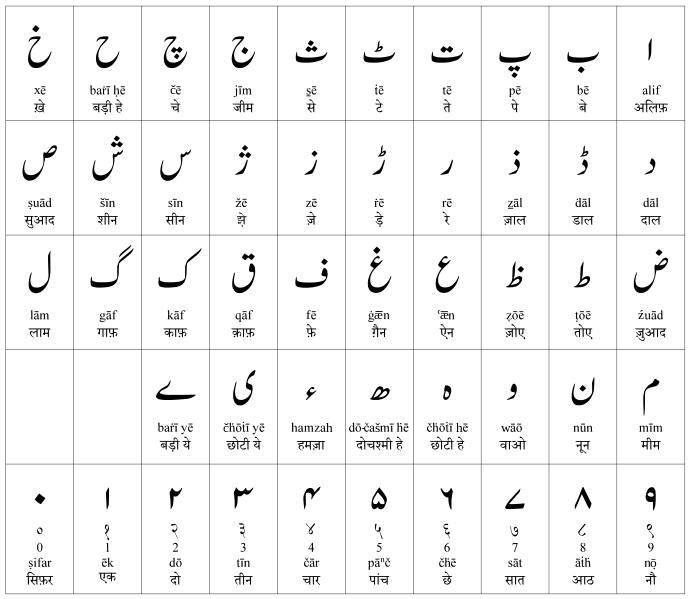

You probably don’t think of letters and punctuation marks as abstract symbols because you’re so familiar with them. However, when a child first encounters the English alphabet it could look every bit as mysterious to them as the symbols below might look to you (unless you’re already familiar with the Urdu writing system).

Each of our letters represents a sound from spoken English. So when we write, you could say that we’re actually drawing sounds.1 You can’t get much more abstract than that!

Similar Shape, Different Meaning…

Some of our letters look almost identical and this can also be confusing for kids. Symbols with the same basic shape change what they represent when they’re drawn in a different orientation.

For example, ‘b’, ‘d’, ‘p’ and ‘q’ all have the same basic shape and so do ‘u’ and ‘n’.

“Learning to Read in English Is Harder Than Learning to Read in Many Other Languages…”

We have fewer symbols in our alphabet than in the Urdu writing system, but this doesn’t make learning to read in English easy – far from it.

In fact, our limited number of letters makes reading more complicated because there are over 40 individual sounds in spoken English that are used to make up words, but we only have 26 letters to represent those sounds.

The shortage of characters in our alphabet means we have to use combinations of letters to represent some sounds. For example, the ‘ou’ combination that makes a specific sound in words like snout and cloud, or the ‘sh’ combination in sheep and fish.

To make matters worse, the sounds of individual letters and letter combinations are not used consistently in different words…

The 40+ sounds in spoken English are represented by over 400 different spelling patterns.2 So your child has10 times more information to learn for written English compared to spoken English.

(If you would like to learn more about the complexities of English compared to other writing systems, see our article: ‘Why Learning to Read in English Is Hard’.

Reading Taxes the Brain

Even when your child has learned to recognise the various spelling patterns, there’s still a lot of work for his or her little brain to do before they can make sense out of a piece of writing…

The visual stimuli from the letters and letter combinations have to be converted into something that represents the individual sounds in spoken language.

Brain scanners have revealed that the language areas of our brains are activated as we read – it’s as if we are hearing our own voices in our heads.

Your child then has to combine the individual ‘sounds’ together in their working memory to construct words.

Finally, they have to hold these constructed words in their working memory while they retrieve the meaning of individual words or phrases from their long-term memories.

To become a fluent reader your child will eventually have to perform all the processes of reading very quickly without having to consciously think about them.

This is an enormous task because it requires various mental processes to work alongside each other automatically:

- Visually recognising individual letters and combinations of letters.

- Making an auditory interpretation of the sounds they represent.

- Understanding how these sounds link together to form the grammatical structures and spellings of syllables and whole words.

- Working out the meaning of the words from the memorised vocabulary and the wider context of the sentence or whole text.

For a good level of comprehension, all these procedures need to be synchronised at speeds that are similar to the rate we process spoken language. Good readers process letters into sounds in less than a tenth of a second.3

However, it takes a great deal of practice before children can process written language this quickly. And when a beginning reader is struggling to decode words, the conscious effort they exert doing this overloads their working memory and reduces their ability to focus on meaning.

(If you want to know more about reading comprehension, see our articles: ‘Reading Comprehension Basics’ and ‘Reading Comprehension Strategies’).

Why Some Parents Get Frustrated With Their Children…

Many parents aren’t really aware of all the complex processes involved in reading. It seems easy to them because they can do it automatically and they’ve forgotten how difficult it was to learn when they were starting out because it was so long ago. So when they see their children struggling with basic words or sentences, they might think their child is just not trying.

Another problem is that some children can get moody when they are asked to read and others sometimes misbehave. When this happens, parents often think the child is being deliberately awkward. This might be true, but it could also be a sign that the child is anxious about reading.

Children in schools often misbehave to conceal the fact they’re struggling, and it’s likely some will also repeat this behaviour at home. Many children would rather be told off for being naughty than risk looking stupid! 4

Why Your Reactions to Your Child’s Difficulties Matter…

If you react disapprovingly when your child makes mistakes, your comments and body language could cause them to experience negative emotions such as anxiety or embarrassment.

These emotions could obviously have a harmful effect on your child’s motivation to read, but they can also be damaging in a less obvious way…

Negative emotions can actually ‘freeze’ our capacity to think.5 They have a physiological effect on the body, which releases stress hormones to prime us for the primitive ‘fight or flight’ response.

In this state, we find it difficult to focus on whatever we are trying to do.

For example, imagine the sort of thoughts that might run through a young child’s head if they’re criticised when trying to read:

- “I’m not good at this”,

- “I don’t like this”,

- “Mum’s mad at me”,

- “Other kids are better than me at this”,

- “I must look stupid.”

Such thoughts are bound to distract the child’s attention away from the text in front of them.

This distraction uses up some of the brain’s processing capacity which causes the child to perform even worse. And their deteriorating performance makes them even more anxious and embarrassed.

As a result, the child can get caught up in a sort of negative feedback loop, or vicious circle, and they could even struggle with words that they might be able to read comfortably in a more positive frame of mind.

Since we tend to remember negative feelings and experiences quite vividly, the child won’t be keen to engage in reading activities with the parent in the future.

Repeated episodes might even put them off reading altogether, and the lack of practice will put them even further behind their peers, making them even more self-conscious about their difficulties.

How Should I React?

Firstly, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with pointing out errors or correcting your child’s pronunciation. Just try to make sure you do it in a matter-of-fact, non-judgemental and supportive way.

You could explain to your child beforehand that getting really good at reading is something that takes time. Tell them that everyone makes some mistakes when they are starting out learning to read and that mistakes are nothing to be ashamed of. In fact, we make mistakes when we learn any new skill…

You could remind them (and yourself) of some of the funny ways they used to say words when they were learning to talk, and how many times they fell over when they were first learning to walk.

We’re sure you didn’t criticise your child every time they fell when they were learning to walk, and you just need to respond to their reading mistakes in a similar way. Point out the error calmly and just move on to the next word.

If a child is corrected by an understanding adult they’re much more likely to stay relaxed and focussed on task. As a result, they will get more enjoyment from reading and look forward to it. They are also more likely to read independently when they become proficient enough, and the extra practice will mean they make faster progress.

Conclusion

Your child will experience less anxiety and make faster progress if you’re supportive and understanding when they are learning to read.

If you’re feeling frustrated about your child’s attitude or progress, try to put yourself in their shoes. Remember that reading is a complex skill that’s especially difficult to master for English speaking children.

The late Irish comedian, Dave Allen, illustrated brilliantly how something that seems simple to an adult, like telling the time from a clock, can be incredibly confusing from a child’s perspective.

We think Mister Allen got the point across much more powerfully than we could ever do in writing, so please take the time to watch this short clip: Dave Allen – “Teaching Your Kid Time.”

Further Information…

You might find some of the other articles in this section of our website interesting.

If you would like more information about teaching your child to read then click on this link.

References:

- What is Reading? CHILDREN OF THE CODE: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c2/magic.htm

- The English Alphabet Code RRF 2011 Dr Diane McGuinness: http://www.rrf.org.uk/pdf/conf2011/Diane_McGuinness_RRF_conf2011.pdf

- THE BRAINS CHALLENGE, CHILDREN OF THE CODE: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/index.htm

- Shame Avoidance, Emotionally Disabling, Children Of The Code: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c3c/avoid.htm, http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c3c/emotion.htm

- Shame, Cognitively Disabling, Children Of The Code: http://www.childrenofthecode.org/Tour/c3c/cognitive.htm