Is handwriting still important? Should your child learn cursive or manuscript or both? How can you help them improve? Find out what the research says…

There are a variety of opinions about how to teach children handwriting.

Different sources suggest teaching children different handwriting styles and there’s a debate about whether children should learn cursive or manuscript handwriting or both.

Some people even suggest that handwriting is no longer important.

We cover these issues in depth in this article so you can make a more informed decision about what’s best for you and your child.

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below:

Disclaimer: We support the upkeep of this site with advertisements and affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you click on the ads or links or make a purchase. There is no additional cost to you if you choose to do this.

Contents:

Summary

- Although we type and text more these days, learning to write by hand still has some benefits: Writing by hand helps to establish brain connections that are important for reading and spelling and it can even help college students learn conceptual information better.

- Some children can learn to write with minimal guidance, but others struggle without direct handwriting instruction. All children can improve the legibility, fluency and quality of their writing if they are taught in a clear and systematic way.

- There are strong claims made by educators on both sides of the cursive verses manuscript debate; however, there’s no conclusive proof that one style of writing is better than the other. Both have potential advantages and drawbacks. No matter how they are taught, many children eventually develop their own style using a mixture of manuscript and cursive and they can actually write faster, and just as legibly, using this approach.

- It’s important that young children get the opportunity to do activities that will help them to develop a good grip and good pencil control. As well as being told how to hold a pencil properly, they should practise tracing curved and zig-zag lines and drawing basic shapes. There are free resources available online for this and colourful wipe-clean books are also useful and appealing to young children.

- If your child hasn’t learned to read yet, it’s really helpful if they can learn the common sounds associated with each letter in the alphabet while they are learning to write them.

- We favour a style of writing that’s been recommended by the UK government and is also used by a number of popular phonics systems and educational publishers in the UK. As well as being easy to read, some of the letters have a slight tail at the end which can easily be extended to join letters together.

- It’s important that your child learns to form the letters using the guidelines on the illustrations because this will help them when they are learning to join the letters together. Writing letters using a ‘ball and stick’ approach can seem simpler at first, but it causes problems later.

- We recommend that the same basic letter formations are used for manuscript and cursive writing because this avoids the confusion of learning new letterforms.

- Avoid lead-in strokes when teaching children cursive writing. They can slow children down and make some letters more difficult to read.

- Tracing letters in wipe-clean books or regular ‘pencil and paper’ workbooks is very helpful when children are learning to write their first letters.

- Although it helps to trace letters when children are first learning them, you should ask your child to write previously learned letters from memory.

- One strategy is to do a few repetitions of one letter until it looks reasonable then introduce a different letter the next day, followed by a little bit more practice of the letter introduced on the previous day. Keep reviewing previously introduced letters every few days until you’ve got through the whole alphabet including capitals and lower case letters.

- It’s important that you don’t expect your child to get all of the letters perfect when they first start to draw them without tracing. Try not to be too critical about their efforts, but talk to your child about which of their attempts are the best ones and why.

- Once your child can write individual letters legibly, you can get them to write out simple words. Whether you decide to do manuscript or cursive first shouldn’t really matter if you’re using the same basic letter formations for both.

- Writing whole words in manuscript isn’t much more difficult than writing individual letters. Get your child to copy words you have written out first or use workbooks where they can trace words.

- Ask your child to measure a finger space between each word when they are writing independently.

- There are 2 main joins in cursive writing: a diagonal join and a washing line join. However, your child will need to practise connecting each join to different types of letters (small, tall, descenders etc.).

- Once again, it helps if children can trace the letters and joins in the words first, and workbooks are really helpful for this:

- Some letters don’t join as naturally as others with cursive writing. Different sources suggest some of the following letters can be easier to read when they aren’t joined to letters that come after them: ‘b’, ‘g’, ‘j’, ‘p’, ‘q’, ‘s’, ‘x’, ‘y’, ‘z’. These are sometimes called ‘break-letters’. You could let your child experiment writing these letters with and without joins and then choose what seems to give the best result.

- Allow your child to do a bit of free writing if they want to, but it can also help if they copy some sentences when they are trying to improve their handwriting.

Is Handwriting Still Important?

In our modern world, much of our ‘writing’ is done on laptops, tablets and smartphones and our messages are sent by emails or texts rather than hand-written letters. So it might seem that becoming proficient at handwriting no longer matters.

However, although we might not write on paper as much as we used to, learning to write by hand does have some benefits…

Cognitive neuroscientists have found that young children can recognise new letters better when they handwrite them rather than type them.1

Similar experiments have been done with adults where they were instructed to learn an unknown alphabet. Those who learned the letters by handwriting them did better in tests than others who had practised typing the letters.2

It seems that writing by hand helps to establish brain connections that are important for reading3 and brain imaging studies have shown that when we read we activate the same brain regions we use for writing. This suggests that we effectively write words in our minds as we read them.4

According to literacy expert Professor Dianne McGuiness, handwriting also helps children learn spellings more efficiently. The hand movements (motor activity) reinforce memory:

“Experimental studies have shown that copying letters is the best way to learn them. Not only this, but copying out spelling words halves the learning rate compared to using letter tiles or a computer keyboard.” 5

There is also some evidence that college students who take notes by hand learn conceptual information better over the long-term than students who write their notes on laptops.6

Does My Child Need Writing Instruction?

A number of educators are of the opinion that children will gradually develop good handwriting with minimal instruction.

For example, reading consultant Margaret Phinney compares the process of learning to write and spell to learning to walk or talk…7

In each case, there is a natural developmental process, children start off with clumsy imitations of the real thing and gradually refine their efforts until they become proficient.

And, since children don’t need direct instruction when they are learning to walk or talk, some people argue they shouldn’t need it when they are learning to write or spell either…

“The little learning machines who learn to walk by walking and talk by talking also learn to read by reading and write by writing.”

Linda Dobson, homeschooling advocate.

The problem with this argument is that written language isn’t really a natural part of human social development in the same way that spoken language is.

The expectation that ordinary people should be able to read and write has only been around for a very short time – no more than a few hundred years in most countries, whereas humans have been communicating in spoken language for many thousands of years.

No doubt, some children can become proficient at reading and writing with minimal direct instruction – as long as they are brought up with literate adults who read to them regularly.

But for every child with a natural flair for literacy, there are others who struggle, and dozens of studies have shown that direct handwriting instruction improves the legibility, fluency and quality of children’s writing.8

Even people with a natural flair for something make better progress when they are given carefully planned and clear instructions. That’s why talented athletes have coaches and gifted musicians take lessons from music teachers.

So, if you want your child to develop good handwriting, he or she will almost certainly benefit from some direct instruction. Why leave it to chance?

Cursive vs Manuscript

There are very different opinions on this…

Some people say that it’s really important to teach cursive (joined-up) writing first whereas others say that children don’t even need to learn cursive at all and should only be taught manuscript (non-joined/print) writing.

Yet another group recommend teaching manuscript first followed by cursive.

Although it’s easy to find strong opinions about handwriting instruction, it’s rather more difficult to locate published academic studies that support the various points of view.

However, Steve Graham, Professor of special education and literacy at Vanderbilt University, has done an extensive review of the research.

According to Graham, there is no strong evidence that one style of writing is better than another.8

Cognitive neuroscientist Karin James hasn’t found that one style of writing is more effective than another either; any kind of lettering done by hand seems to affect brain circuitry in a similar way.4

Professor Graham has suggested some reasons why teaching manuscript first might be beneficial:

- Manuscript writing can be easier to read than cursive.

- Learning manuscript might make it easier for children to read printed texts, which are almost always written in manuscript.

- There is some evidence that manuscript is easier to learn than cursive.

Graham also points out that many children learn to write a few printed letters when they are in preschool, so it might be easier to continue with the same style they’ve started with.

We agree with Graham that manuscript is usually easier to read. In fact, it’s probably the reason why many forms instruct us to ‘print’ our details.

Whether or not writing in manuscript really makes it easier for children to learn to read isn’t something that has been proved conclusively, although it does seem to be a reasonable argument.

However, not everyone agrees that manuscript is easier to learn than cursive.

For example, the ‘Logic of English’ company, which produces literacy resources and training for teachers, recommends beginning with cursive.9

They list 6 advantages of cursive over manuscript:

- It is less fine-motor skill intensive.

- All the lowercase letters begin in the same place on the baseline.

- Spacing within and between words is controlled.

- By lifting the pencil between words, the beginning and ending of words are emphasized.

- Cursive writing makes it more difficult to reverse letters such as b’s and d’s. Many children reverse these letters when they first write in manuscript.

- The muscle memory that is mastered first will last a lifetime.

- It is less fine-motor skill intensive.

Some older people, such as the late author and educator Sam Blumenfeld, have argued that we should teach cursive first because that was how they were taught years ago.

They claim that this helped the older generation develop better handwriting than people of more recent generations.10

The idea that the older generation had better handwriting could be disputed, but even if it’s true there might be alternative explanations for this…

For example, there are many different styles of cursive writing and it might just be that the types of cursive taught years ago looked more elegant than some of the more modern scripts.

Changes in writing instruments may also have contributed to differences in the appearance and legibility of handwriting over the years…

In her ‘Vox’ article, Libby Nelson noted that people really started complaining about the decline of handwriting when ballpoint pens became popular in the 1960s.11

The ink in a fountain pen flows easily because it’s thin and so letters can be joined effortlessly with natural, flowing strokes.

In contrast, the ink in ballpoint pens is much thicker and we have to apply more pressure to make it come out of the pen. This means it takes more effort to keep the pen in contact with the paper and so it’s more difficult to join letters together in a flowing cursive style.

We also need to hold ballpoint pens at slightly different angles to fountain pens and this can affect the appearance of our writing even if we do choose to write in cursive. There’s an interesting short video about the handwriting debate in Nelson’s article:

Science writer Philip Ball is sceptical about the claimed advantages of cursive writing.

In an article for Nautilus magazine, he points out that the issue is difficult to study because it’s hard to find groups of children whose literacy instruction in school is identical except for the style of handwriting they are taught.

He also says that a lot of the “evidence” that gets quoted is of questionable quality and some claims may even be fabrications because it’s often impossible to find reliable sources.12

Some people claim that a good reason to teach cursive is that it’s faster than manuscript. However, Ball mentions a study comparing the writing speeds of French children with French-speaking children from Canada.

French children are all taught cursive from the start, whereas there is more flexibility of instruction in Canada. It turned out that children taught manuscript could actually write faster than those using cursive, but children who had evolved their own style using a mixture of manuscript and cursive were fastest of all.

Professor Graham has also found that the fastest writers use a mix of printed and cursive letters and he says they gain speed without sacrificing legibility.13

Ball mentions another study comparing Canadian and French primary children which found that those who learned only cursive handwriting performed more poorly than those who learned manuscript, or both styles, in recognizing and identifying the sound and name of individual letters.

However, a similar study published in 2012 in the journal ‘Language and Literacy’ found that students who learned cursive had better spelling and syntax. But students who learned printing in the first grade and then began cursive writing in the second grade made the least progress in spelling.14

One explanation for this was that learning a different style of writing before the first style is fully mastered can confuse children.

Most educators agree that whatever style of writing children learn, they need to practise until they can do it without thinking. Once they’ve developed automatic handwriting, they are then free to concentrate on spelling, higher-level thought, and written expression.3

What Do We Think?

We don’t think there is sufficient robust evidence to say that one style is better than another with any degree of certainty.

Cursive and manuscript both have potential advantages and drawbacks and it’s probably better to go with your personal preferences than to worry too much about what the limited research suggests.

The fact that different studies have sometimes produced contradictory results suggests that any advantage of teaching one style before another is probably slight.

Although writing is important, the ways children are taught to read and spell probably have a much greater impact on their long-term literacy skills than the way they are taught to write. See our articles on teaching phonics and spelling for more information about how to do these things effectively.

Since there is some evidence to suggest that children write more quickly when they use a mixture of manuscript and cursive, there might be some benefit in teaching both styles.

We think it’s possible to teach both print and joined-up writing in a way that doesn’t confuse children and we’ll explain how to do this later in this article.

In our opinion, the most important considerations are that children should be able to write quickly and legibly. What style they use is trivial in comparison.

In fact, Professor Graham has observed that many children eventually modify whatever styles of writing they are initially taught anyway:

“Regardless of which script(s) a child is taught, it is important to realize that children will inevitably develop their own style. …eliminating or modifying some connecting strokes. …Thus, teachers who insist on a strict adherence to a particular model are likely to frustrate not only themselves, but their students as well.” 8

Pre-Writing Skills

Very young children don’t have the fine motor skills and coordination to write letters legibly. So it’s important that they get a chance to do activities that will help them to develop a good grip and good pencil control.

If younger children really struggle to hold a pencil, they might need to develop their gripping ability first, and this can be done with a variety of play activities such as those suggested by occupational therapy assistant Heather Greutman in this article.

TheSchoolRun website has a very good short video about teaching a good pencil grip which you can view below:

TheSchoolRun have another informative video about correcting a bad grip.

The video below from ‘Jolly Phonics’ shows a teacher instructing her children how to hold a pencil correctly. She likens the fingers holding the pencil to ‘froggy legs’:

This clip from the ‘magic link’ handwriting programme also has some useful pointers for pencil grip:

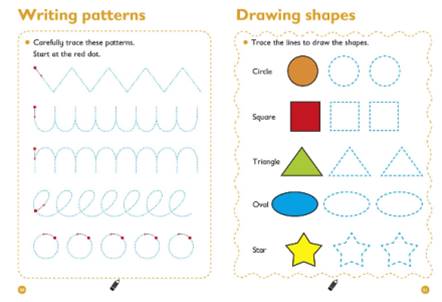

Heather Greutingman advises that children should develop their pencil control first by learning how to draw some basic lines and shapes before they practise writing letters and this does seem like sensible advice.

Greutman says that the above lines and shapes need to be practised in a specific sequence when children are at a particular age. However, we don’t think you need to follow these guidelines too rigidly.

There are often considerable differences between children of the same age and the more opportunities you give your child to practise particular skills the sooner they will master them.

Our youngest child was able to write whole words quite legibly when she was still only 3-years old.

Tracing curved and zig-zag lines such as the ones on this link can also be useful activities for developing hand-eye coordination and pencil control in children, as can tracing more interesting shapes and simple pictures like the ones on this link and this one.

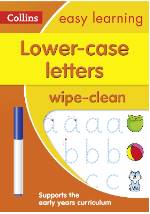

Our children enjoyed doing activities in wipe-clean books similar to the ones below. These are often more colourful and appealing than printed sheets and each page can be re-used multiple times.

There are also some very good shape and letter-tracing apps that can help to prepare children for writing their first letters on paper. We’ve described some free ones we like in an article that you can access from the link above.

Teaching Your Child to Write Their First Letters

If your child hasn’t learned to read yet, it’s really helpful for them to learn the common sounds associated with each letter in the alphabet while they are learning to write them.

At this stage, don’t worry about teaching letter names because these don’t actually help with reading. See our article, ‘Should I Teach My Toddler Letter Names’ for more information about this.

As we mentioned earlier, no style of writing has been definitively shown to be superior to another. Your decision to teach a particular style to your child could just be based on your own personal preference, or you might want to follow the style they teach in your local school.

However, if you’re unsure, you might want to consider the following suggestions…

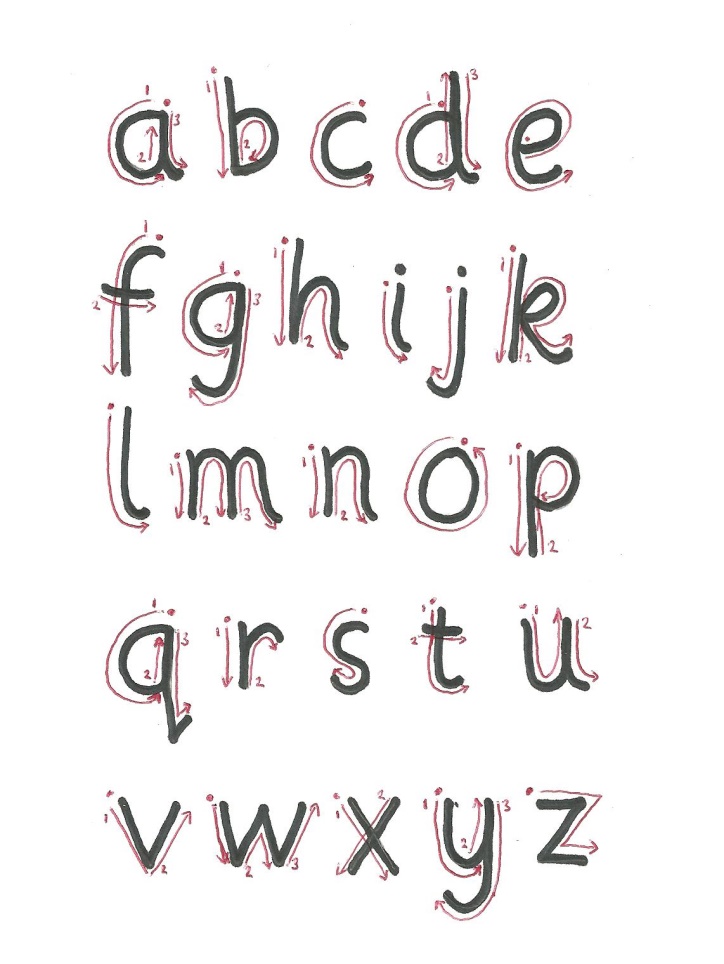

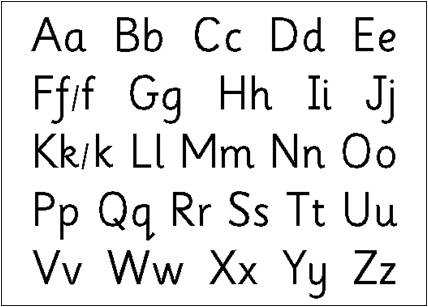

We favour the style of writing shown in the illustrations below. The letter formations are identical to the ones suggested by the UK government in its original phonics programme, ‘Letters and Sounds’,15 and they are in line with the current UK National Curriculum.

A number of popular phonics systems and educational publishers in the UK also use the same style.

The red dots show the starting point for writing each letter and the arrows indicate the direction of each pencil stroke:

The above style is similar to ‘Sassoon Infant’ typeface, which was developed by a researcher who was investigating which letterforms children found easiest to read.16

As well as being easy to read, some of the letters have a slight tail at the end which can easily be extended to join letters together. These are helpful when children are making the transition from manuscript to cursive writing.

It’s important that your child learns to form the letters using the guidelines indicated by the arrows in the illustrations above because this will help them when they are learning to join the letters together. Writing letters using a ‘ball and stick’ approach can seem simpler at first, but it causes problems later.

We recommend that the same basic letter formations are used for manuscript and cursive writing because this avoids the confusion of learning new letterforms.

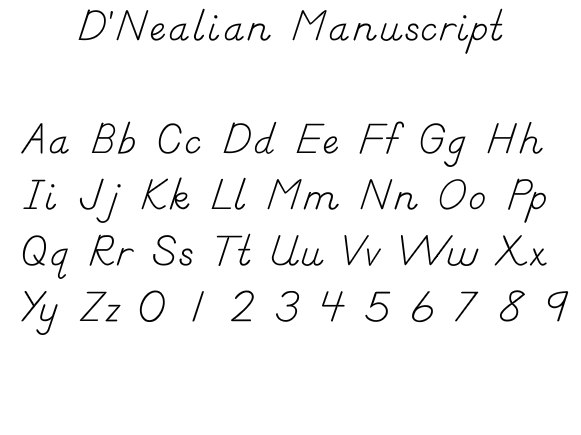

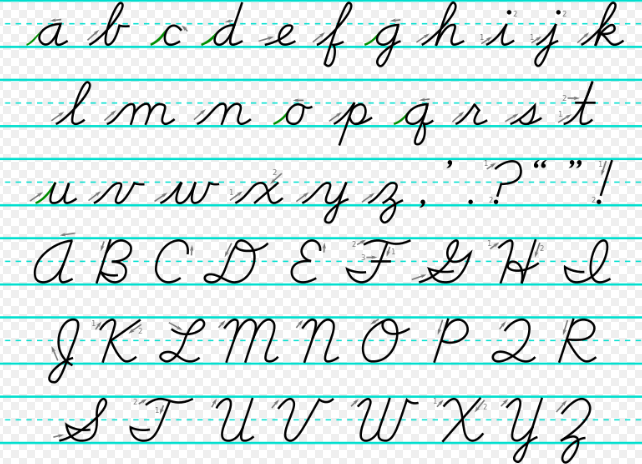

Some writing styles have letters that look quite different in the manuscript and cursive forms.

For example, the illustration below shows the D’Nealian manuscript next to the D’Nealian cursive style. Notice that the manuscript letters are very similar in style to the ones we illustrated above, but look how some of the letters have changed in their cursive form:

You might also have noticed that the lower case letters in the De’Nealian cursive style have lead-in, or entry strokes.

It’s quite common for children to be taught to write letters with lead-in strokes when they are learning cursive writing, but we think this is unnecessary.

Some people claim that lead-in strokes make it easier for children because every letter starts from the same place – the baseline. However, as we pointed out earlier, this isn’t always true. Letters that follow ‘w’, ‘o’, ‘r’ and ‘v’ don’t start from the baseline in many cursive styles.

Children who are taught to practise starting every letter from the baseline can get confused when they start joining up words containing ‘w’, ‘o’, ‘r’ and ‘v’ because they think they have to return towards the baseline after every letter.

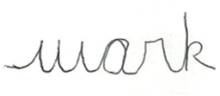

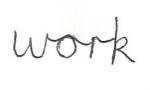

For example, we observed a child write the word ‘work’ in the following way:

As you can see, the letter ‘o’ looks more like an ‘a’ and the ‘r’ looks a bit like an ‘n’.

In fact, written this way, it could be mistaken for a word that’s actually quite rude in the U.K!

It’s easier, and more legible, to join the letter ‘o’ with a more horizontal curved stroke from the top of the ‘w’, and the letter ‘r’ can just be extended towards the ‘k’, as in this example:

This sort of horizontal stroke is sometimes called ‘the washing line’ join.

A teacher in our local school told us that many children have a problem developing this join when they’ve been drilled to always start from the baseline with lead-in strokes.

Consequently, we think lead-in strokes can make the transition to cursive more complicated. They can also slow children down when they are writing and make some letters more difficult to read.

Notice below that the capital letters in the style we recommend are also quite straightforward to write and easy to read. They are much less elaborate than some of the D’Nealian cursive upper case letters shown earlier.

We found that wipe-clean books such as the ones shown below were very helpful when our children were learning to draw letters.

Apart from the ability to use the pages again and again, a good thing about the above books is that children get to practise tracing letters on dotted lines first by following the directions of the arrows. Research has shown that this beneficial for beginning writers.8

There are a number of ‘pencil and paper’ workbooks available that also get children to trace the letters first.

We found the Collins series of handwriting workbooks really helped our children to improve their writing skills, but there are others that use similar writing styles.

Your child doesn’t have to learn to write the letters in alphabetical order.

Some books get children to practise tall and short letters separately followed by letters that descend below the lines on the page, such as ‘y’, ‘g’ and ‘p’.

Other people suggest grouping letters together according to different criteria, such as how frequently they occur in print, but we’re not aware of any research that proves one particular order of instruction is better than another.

Research by Professor Steve Graham found that children were more likely to have trouble writing the following letters legibly:

q, z, u, a and j

So you might need to allow more time for practising these letters. However, there is likely to be considerable variation between children and your child might find some of the other letters more difficult to write.

The important thing is that your son or daughter practises each letter of the alphabet until they can reproduce it legibly from memory.

One strategy is to do a few repetitions of one letter until looks reasonable then introduce a different letter the next day, followed by a little bit more practice of the letter introduced on the previous day.

Although it helps to trace letters when children are first learning them, you should ask your child to write previously learned letters from memory.

Keep reviewing previously introduced letters every few days until you’ve got through the whole alphabet including capitals and lower case letters.

It’s important that you don’t expect your child to get all of the letters perfect when they first start to draw them without tracing.

Try not to be too critical about their efforts, but talk to your child about which of their attempts are the best ones and why.

Writing Their First Words

Once your child can write individual letters legibly, you can get them to write out simple words.

You can choose to let your child practise writing words in manuscript first or go straight to cursive if you prefer. Which you decide to do first shouldn’t really matter if you use our suggested font, as you will be using the same basic letter formations for both.

Manuscript…

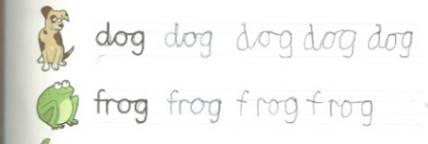

Writing words in manuscript isn’t much more difficult than writing individual letters. Get your child to copy words you have written out first or use workbooks like the ones shown below where they can start off tracing words.

Perhaps the greatest difficulty children have when learning to write words in manuscript is getting the spacing right.

They sometimes leave too much space between individual letters in words and not enough space between words.

This should improve with gentle guidance and it can help if you ask your child to measure a finger space between each word until they get the hang of it.

Cursive…

Learning to join the letters for cursive writing can also be quite straightforward, although it does take a bit of practice before words will look neat and legible.

There are really only 2 main joins: a diagonal join and a washing line join. However, your child will need to practise connecting each join to different types of letters…

The illustration below shows how a diagonal join connects from the base of one letter to the top of another letter. The joining stroke continues up to the starting point of the next letter, which is then drawn in the normal way.

This join can be used to link to small letters and descenders that start with a downward stroke. For example, p, i, j, m, n, r, u, v, w and y.

A washing line join can be used to connect to the above letters in a similar way.

Washing line joins are normally used after w, o, r and v. Once again, the joining stroke continues to the starting point of the next letter, which is then drawn in the normal way:

Joining to a tall letter isn’t much different, but the diagonal join should connect as shown on the diagram on the left rather than the one on the right:

The washing line join connects to tall letters in a similar way:

When connecting to the curved side of a letter, such as a, c, d, g, o and q, the joining line should curve around the shape of the letter until it reaches the normal starting place. Then stop and draw the letter in the normal way by going back round to the left.

As we mentioned previously, it helps if children can trace the letters and joins in the words first, and workbooks like the ones below are helpful for this.

Don’t expect your child’s first attempts to be flawless. Here’s an image of one of our children’s first effort at the washing line join:

As you can see, these were far from perfect, but with just a bit more practice she was able to join up whole words quite legibly, and she was still only 4 years old at the time…

Break Letters

While all of the letters of the alphabet can be joined, some educators recognise that a few letters don’t join as naturally as others with cursive writing.

Many people no longer join capital letters when they write and it’s becoming increasingly common to omit the joins for some of the lowercase letters too. In fact, the 2013 programme of study for the English National Curriculum in the UK says:

“Pupils should be taught … to understand which letters, when adjacent to one another, are best left unjoined.” (Page 28)

Opinions vary, but different sources suggest some of the following letters can be easier to read when they aren’t joined to letters that come after them:

b, g, j, p, q, s, x, y, z.

As we’ve already discussed, many people eventually drop some of the joins in their writing no matter which style they are taught initially, and this also seems to speed up their writing.

So it seems reasonable to give children the option of doing this for some letters when they begin their writing instruction. Perhaps you could let your child experiment writing these letters with and without joins and then choose whatever seems to give the best result.

Practising Writing

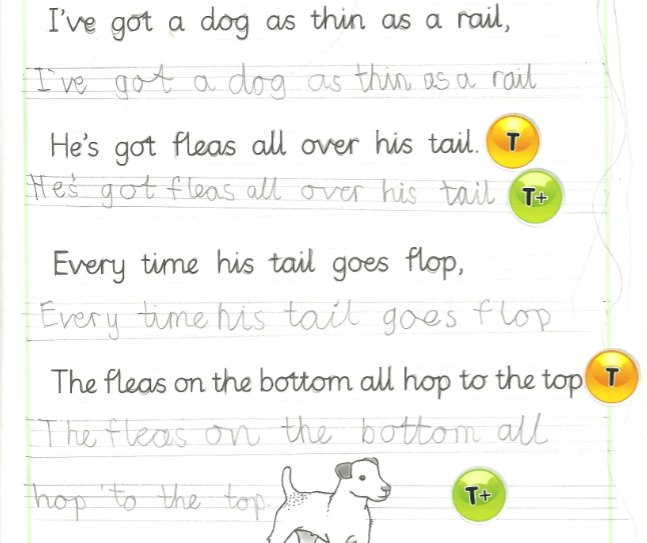

There’s nothing wrong with letting your child do a bit of free writing if they want to, but it also helps for them to copy some sentences when they are trying to improve their handwriting.

Here’s an example of a poem our youngest child copied from a workbook when she was still only 4 years old. Notice that she has chosen to do some break letters. She hasn’t joined the letter g in ‘got’ or the letter f in ‘flop’. She’s also avoided joining some letters to ‘s’.

If you want your child to develop their all-round writing skills alongside their handwriting, they will need to develop an understanding of the structure of sentences and paragraphs.

This is best taught in an incremental way, and we discuss how to do this in another article.

Further Information…

TheSchoolRun website contains a variety of useful educational resources, including help with handwriting and spelling.

The Magic Link Handwriting programme is very popular because it gives very clear and thorough instructions for teaching handwriting to young children. The style is similar to the one we’ve suggested in this article and it gets great reviews on Amazon.

Hooked on handwriting is another popular programme.

References:

- Longcamp, M. et al. (2005), The influence of writing practice on letter recognition in preschool children: A comparison between handwriting and typing, Acta Psychologica, Vol. 119, Issue 1, May 2005, Pages 67-79: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15823243

- The University of Stavanger. “Better learning through handwriting.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 24 January 2011. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/01/110119095458.htm>.

- 5 Brain-Based Reasons to Teach Handwriting in School. Psychology Today.

- O’Callaghan, T. (Nov. 1st 2014) Goodbye paper: What we miss when we read on screen, New Scientist Magazine.

- McGuiness, D. (2002) A Prototype for Teaching the English Alphabet Code, Reading Reform Foundation Newsletter No. 49 page 21: http://www.rrf.org.uk/pdf/nl/49.pdf

- Take Notes by Hand for Better Long-Term Comprehension, Association for Psychological Research (April 2014): http://www.psychologicalscience.org/index.php/news/releases/take-notes-by-hand-for-better-long-term-comprehension.html

- Invented Spelling, Margaret Phinney, The Natural Child Project: http://www.naturalchild.org/guest/margaret_phinney2.html

- Graham, S. Want to Improve Children’s Writing? American Educator, VOL. 33, NO. 4, Winter 2009-2010.

- Starting with Manuscript or Cursive, The Logic of English.

- Blumenfeld, S. (2012) How Should We Teach Our Children to Write? Cursive First, Print Later!, The New American: https://www.thenewamerican.com/reviews/opinion/item/11707-how-should-we-teach-our-children-to-write

- Nelson, L. (2016), Ladislao José Biro invented a “miraculous” pen and changed the way we write, Vox: https://www.vox.com/2016/9/29/13097948/ladislao-jose-biro

- Ball, P. (2016) Cursive Handwriting and Other Education Myths, Nautilus Magazine: https://nautil.us/cursive-handwriting-and-other-education-myths-236094/

- Tierney, J. (2007) Ending the curse of cursive, TierneyLab, NY times January 2007: http://tierneylab.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/01/23/ending-the-curse-of-cursive/?_r=0

- Learning cursive in the first grade helps students, Quebec study finds, ScienceDaily (2013): https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/09/130913113847.htm

- Letters and Sounds: Principles and Practice of High Quality Phonics, Primary National Strategy, Department for Education and Skills (2007).

- Sassoon® Fonts:http://www.sassoonfont.co.uk/

Image Attributations

D’Nealian Manuscript

Shruti14 at English Wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:D%27Nealian_Manusript.png

D’Nealian Cursive

By AndrewBuck (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cursive.png