This approach, which is sometimes described as ‘look and say’, encourages children to learn words as whole units rather than focusing on the letters. A number of infant reading programmes use this method and many children are taught so-called sight words this way. But how effective is it?

Click here for a summary of this article, or browse the contents of the main article below…

Disclaimer: We support the upkeep of this site with advertisements and affiliate links. We may earn a small commission if you click on the ads or links or make a purchase. There is no additional cost to you if you choose to do this.

Contents:

Summary

- Children can appear to make fast progress with this method, but their progress usually stalls if they don’t learn the relationships between letters and sounds.

- The predictable and repetitive texts used with some whole word programmes can give an exaggerated impression of a child’s true reading ability.

- It can be easy for a child to mix up similar looking words when they use a whole word strategy.

- Learning whole words doesn’t activate the brain areas which are important for reading as much as phonics instruction does.

- Eye tracking technology shows that skilled readers focus on all the letters in words rather than the shapes or outlines.

- Reviews of classroom studies show that children make better progress when they are taught to read using phonics-based programmes rather than a whole word approach.

- Whole word instruction doesn’t help very much with spelling.

Background Information

In the early stages of whole word instruction, children learn to read by recognising the shapes or outlines of words. But, according to critics, learning to recognise a significant number of words from their shapes can be a slow process.

Although children might be able to recognise a few words successfully at first, progress often slows considerably as a greater number of words are introduced.

It seems that some children can eventually figure out letter-sound relationships from the words they have learned in this way. But for those who aren’t able to do this, their only strategy for learning new words is rote learning by continuous repetition.

Some reading programmes use predictable and repetitive books to help children learn whole words, and these can give the impression that youngsters are making good progress. But it might just be that children are able to figure out patterns in the texts due to the recurring phrases. Illustrations can also make it easy for a child to guess the one or two different words on each page.

If a child is presented with a less predictable passage that doesn’t contain illustrations, he or she might struggle with words they had previously been able to figure out in a repetitive text.

Alison Clarke has made a very good short video clip outlining the problems children would encounter if they actually attempted to read the words in these books without the help of the repetitive phrases and pictures.1

Similar Words and Limited Visual Memory

Another problem with the look and say approach is that words with similar looking outlines, like house and horse, or girl and grill can easily be mixed up.

Additionally, there seems to be a limit to the number of abstract visual symbols people can remember. Some people argue that it’s possible to learn many thousands of words without focussing on individual letters, and they often cite more visually complex writing systems like Chinese and Japanese to support their case.

However, contrary to popular belief, Chinese and Japanese writing systems have a limited number of symbols that need to be remembered, and the number of these symbols is many times smaller than the tens of thousands of words that can be found in an English dictionary.2

Laboratory Studies

The difficulty of learning whole words has been demonstrated experimentally by researchers using invented alphabets with words constructed in unusual ways.

For example, one study used alternative letter symbols stacked on top of each other rather than side-to-side. A group of volunteers was asked to learn the words as whole shapes, while another group was taught how the individual letters were arranged to make the words.

The whole word/shape group made faster progress on the first day, but on following days, when new lists of words were introduced, the whole word/shape group quickly forgot the earlier words they had learned and lost ground compared to the letters group.3

Some Whole word advocates say that children eventually pick up phonics knowledge independently after they’ve learned enough words. However, although some children can do this, there is evidence that others can find it difficult to infer the associations between letters and sounds, even when they appear to have been presented in an obvious way.

For example, Byrne (1991) taught children to recognise short words by pairing them up with pictures. Examples included ‘fat’ and ‘bat’. However, in a subsequent test, when they were asked to judge whether a printed word said ‘fun’ or ‘bun’, the children were unable to demonstrate that they had figured out the sounds represented by the first letters.4

In a detailed article published by the American Psychological Society in 2001, researchers who considered the evidence from laboratory studies concluded:

“… learning correspondences between letters and sounds is more productive (so there is more transfer to new words) than learning whole words, even though learning whole words may be faster at first.” 4

Brain Studies

Stanford Professor, Bruce McCandliss found that beginning readers who focus on letter-sound relationships increase activity in the brain areas that are engaged the most by skilled readers (regions in the left hemisphere).

In contrast, these brain regions are not activated to the same degree when readers focus on learning whole words.5

So it appears that different teaching strategies for reading have different neural impacts, and that teaching phonics is better at activating the brain areas that are most important for skilled reading.

“… strong left hemisphere engagement during early word recognition is a hallmark of skilled readers, and is characteristically lacking in children and adults who are struggling with reading.” 5

Stanislas Dehaene, a neuroscientist who specializes in reading and number sense, very much favours “a strong phonics approach” to teaching reading and he is against whole-word or whole-language approaches. His opinion is based on his expert knowledge of the research in this area:

“… analysis of how reading operates at the brain level provides no support for the notion that words are recognized globally by their overall shape or contour. Rather, letters and groups of letters … are the units of recognition.” 6

Eye Tracking Studies

Experiments have been done using sophisticated technology that tracks the detailed movements of a person’s eyes when they are reading. These experiments confirm the findings from brain studies (mentioned above) which showed that we process the individual letters in words when we read, rather than the outlines or shapes of words.7

This can even be demonstrated without sophisticated technology by changing the outlines of words.

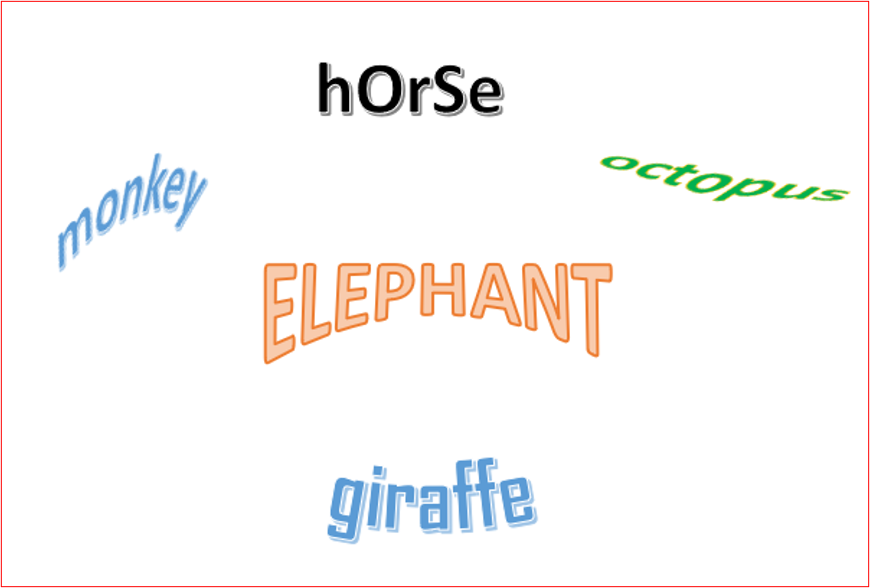

For example, you can probably read each of the words below even though we’ve made various adjustments to alter their normal appearance:

The cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene has written:

“… our visual system pays no attention to the contours of words or to the pattern of ascending and descending letters: it is only interested in the letters they contain. … our capacity to recognize words does not depend on an analysis of their overall shape.”

Dehaene, S. (2009), Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read, Penguin Books.

Studies have also revealed that all the letters in a word are processed by skilled readers, not just the first or last letters.

Classroom Studies

There has been a lot of research done on reading instruction over the past few decades and there have been several extensive independent reviews of this research in some of the main English speaking countries.

Every one of these major reviews has concluded that children make better progress when they are taught to read using phonics-based programmes rather than a whole word approach. See our article, ‘Is Phonics the Best Way to Teach a Child to Read?‘ for more information on these reviews.

Do Some Words Need to Be Learned By Sight?

Words that appear a lot in children’s literature are sometimes called ‘high-frequency words’. Some educators encourage children to learn high-frequency words as whole words and they refer to them as ‘sight words‘.

The idea is that kids will learn to read faster if they focus on learning high-frequency words ‘by sight’ rather than learning to decode them using the letter-sound relationships taught in phonics lessons. This argument sounds logical enough but we’re inclined to disagree with it.

Although the strategy gives the illusion of fast progress there is a negative trade-off because time spent learning whole words by sight means less time spent learning the principles of phonics.

Even if a child has some early success learning whole words, this could get them into a habit of ignoring the letters, which could cause serious problems later on. It’s a bit like building a house without proper foundations – it goes up quicker, but cracks will soon begin to appear and the finished product won’t be up to standard.

Promoters of the sight word strategy often point out that there are lots of high-frequency words with irregular spellings, which are more difficult to read using phonics rules. However, around half of the most common words are completely regular and the vast majority of the others contain some regular letter-sound correspondences. Research shows that children are better at reading irregular words after they have developed a sound foundation in phonics.

Completely irregular words are very rare. The word ‘eye’ is one of the most often quoted examples, but even this is similar to other common words such as ‘bye’ and ‘dye’. And even for the most irregular words, letter patterns still need to be learned before a child will be able to spell them correctly (see Whole Word and Spelling below). Consequently, it would be a mistake to rely on memorising the outline of irregular words without paying any attention to the individual letters.

See our articles ‘Common Objections To Phonics’ and ‘Should I Teach My Child Sight Words?’ for a more detailed discussion of this point.

Whole Word and Spelling

Although this article is about learning to read, it’s important to be aware that the way a child is taught to read can also have a significant impact on their future spelling ability.

Whole word instruction does very little to help children get to grips with spelling. That’s because the most efficient way to spell is by considering the individual sounds in a word and the letters that represent those sounds. With whole word, children only really focus on the outlines or shapes of words.

Some teachers do encourage children to say the letter names too, but saying the letter names (rather than the sounds) is an inefficient way to learn spellings.

Click on the following link if you would like to know more about teaching spelling with phonics.

Conclusion

Although some children can learn to read by starting off with a whole word approach, evidence from a variety of sources suggests that it is more effective to use phonics as the main method of instruction.

Phonics takes more time to show results in the early stages, but children will become better readers and spellers in the long-run if they are taught phonics explicitly and systematically.

“Getting children to learn sight words is like throwing them some fish. Helping them to learn phonics is like teaching them how to fish.”

If you want to teach your child to read for free, you should find some of the links below helpful.

Further Information…

Click on the following link if you would like to learn more about teaching your child to read using phonics.

Another way to learn more about phonics is to register with some of the specialist reading programmes that offer free trials.

For example:

Parents and teachers can register for a 30-day free trial with Reading Eggs. This allows you to access over 500 highly interactive games and fun animations for developing Phonemic awareness, Phonics, Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension.

A 30-day free trial is also available from ABCmouse.com. This is a leading online educational website for children ages 2–8. With more than 9,000 interactive learning activities that teach reading, math, science, art, music, and more.

Although it’s not quite free, you can get a 30-day trial with the award-winning Hooked on Phonics programme for just $1.

IXL Learning cover 8000 skills in 5 subjects including phonics and reading comprehension. You can click on the following link to access a 7-day free trial if you live in the US.

If you live outside of the US you can get 20% off a month’s subscription if you click on the ad. below:

If you want to know how to improve your child’s reading comprehension, see the following article: Reading Comprehension Basics.

Click on the following link if you would like to know more about teaching your child to write.

References

- Clarke, A. Spelfabet, Predictable or repetitive texts: https://www.spelfabet.com.au/2015/08/predictable-or-repetitive-texts/

- Look and Say, dyslexics.org.uk: https://www.dyslexics.org.uk/look-and-say-whole-language-teacher-training/

- Nurture a Reader Blog. Learning Words as Whole: An Experiment (Oct. 2011). Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention, Stanislaus Dehaene (pp. 225-226): http://nurtureareader.blogspot.co.uk/2011/10/learning-words-as-whole-experiment.html

- Study sourced from Rayner, K. et al. (2001), HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE INFORMS THE TEACHING OF READING. American Psychological Society. VOL. 2, NO. 2, NOVEMBER 2001

- Stanford study on brain waves shows how different teaching methods affect reading development: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2015/may/reading-brain-phonics-052815.html

- Source: Human Neuroplasticity and Education Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Scripta Varia 117, Vatican City 2011.

- McConkie & Rayner, 1975; Rayner, 1975; Rayner & Bertera, 1979. Study sourced from Rayner, K. et al. (2001), HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE INFORMS THE TEACHING OF READING. American Psychological Society. VOL. 2, NO. 2, NOVEMBER 2001