A helpful guide to teaching about digraphs at home or in school. When and how they are best taught, teaching strategies and free digraph worksheets.

Contents:

- Why Teach Digraphs?

- When to Teach Digraphs

- When are digraphs taught in Schools?

- Strategies for Teaching Digraphs

- Teaching split digraphs

- Should You Teach Blends or Digraphs First?

- What Order Should I Teach Digraphs?

- A Suggested Teaching Sequence for Digraphs and Trigraphs.

- Teaching Sequences for Digraphs and Trigraphs in Some Popular Phonics Programmes

- Free Digraph Worksheets

- References

Why Teach Digraphs and Trigraphs?

Teaching digraphs and trigraphs is important because hundreds of common words in written English contain one or more digraphs. Children find these words much harder to read and spell if they can’t recognise digraphs.

For example, all the everyday words below contain digraphs that we’ve highlighted in colour…

Children, shop, rain, feet, coat, car, fork, flower, cloud, coin, elephant, mountain, farmer, sheep, shopping, chair, torch, shout, shorts, shirt.

Many digraphs represent different sounds from the individual letters that make them up, so a lot of children can find it hard to recognise digraphs without some direct instruction.

Some children can eventually learn to recognise digraph patterns on their own if a supportive adult has read to them a lot over an extended period.

However, most children are likely to grasp digraphs more quickly if a teacher has clearly explained the idea and systematically introduced them to plenty of examples.

When Are Digraphs Taught in Schools?

The exact age when children are taught digraphs can vary in different countries. In England, children are introduced to digraphs when they join reception classes in the academic year when they turn 5 years old.

Children join Kindergarten at a similar age in the USA and they might also be taught about digraphs.

Several simple digraphs such as the double consonants ‘ff’, ‘ll’ and ‘ss’ are normally introduced early in the first term in English schools.

A variety of other consonant digraphs such as ‘ch’, ‘sh’ and ‘th’ may be introduced later in the first term before children are taught vowel digraphs. Children in Kindergarten in the USA may also meet these digraphs.

By the time they finish reception, English children might have been taught more than a dozen vowel digraphs and they are introduced to many more vowel and consonant digraphs in year 1 (the academic year when children become 6 years old).

We’ve provided a more detailed list of the digraphs commonly taught in English Schools below. However, there can be some variation in when particular digraphs are introduced in different schools.

Most schools in England broadly follow the guidelines in Government’s Letters and Sounds phonics programme1. However, schools are free to choose alternative commercial programmes, or use programmes developed by themselves, as long as they match the principles of high-quality phonics work outlined in the Letters and Sounds guidance document.

Like the UK, different regions and different schools in the USA might teach things at slightly different times, but the digraphs shown below are widely taught in the first couple of years in most English-speaking countries.

Digraphs for Reception / Kindergarten

(Some trigraphs are also included in this list)

Phase 2 (starts early in reception for up to 6 weeks)

ck ff ll ss

Phase 3 (starts in the first term of reception and lasts up to 12 weeks)

zz qu ch sh th ng ai ee igh oa oo ar or ur ow oi ear air ur eer

No new digraphs or trigraphs are introduced in phase 4 of letters and sounds.

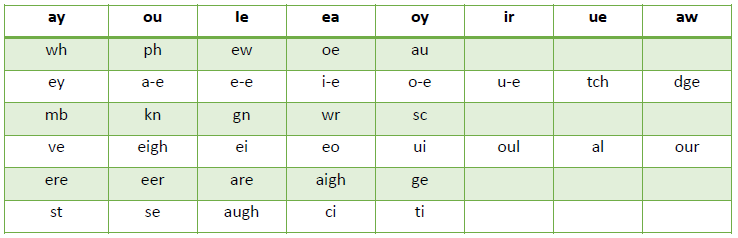

Digraphs for Year 1 / First grade in the USA

(Some trigraphs and quadgraphs/tetragraphs are also included in this list).

Phase 5 (lasts throughout the whole of year 1)

| ay | ou | le | ea | oy | ir | ue | aw |

| wh | ph | ew | oe | au | ey | a-e | e-e |

| i-e | o-e | u-e | tch | dge | mb | kn | gn |

| wr | sc | ve | eigh | ei | eo | ui | oul |

| al | our | ere | eer | are | aigh | ge | st |

| se | augh | ci | ti |

See the teaching sequence for digraphs and trigraphs in Letters and Sounds for example words from the programme for each digraph and trigraph.

Strategies for Teaching Digraphs

- Avoid jargon in your explanations. Describe what digraphs are in simple child-friendly language. There’s no need to use the term ‘digraph’. Although this terminology might be important for academic discourse, it doesn’t help in the classroom.

Non-essential jargon just gives kids something extra to learn, which increases their cognitive load and makes concepts harder to grasp.

It’s better to use words that mean something to kids. For example, ‘These 2 letters stand for one sound in this word’, or ‘This is a 2-letter spelling for one sound’, or ‘This is a letter-team. These 2 letters team up in words, and when we see them, we only say one sound’.

Some academics are keen to point out that it’s technically incorrect to say ‘these two letters make one sound’ or ‘these 2 letters say one sound’. This is because letters don’t make or say sounds, they represent sounds. However, we think kids are smart enough to realise that letters don’t actually make or say sounds on their own, so don’t beat yourself up if you occasionally use the ‘wrong’ phrase.

- Introduce one new digraph at a time and keep the sessions fairly short. Established phonics programmes such as Letters and Sounds and Jolly Phonics teach around 3 – 5 letters or digraphs per week in daily sessions lasting around 20 minutes, so this is a reasonable pace to aim for.

- Use visual picture cues and actions when you introduce new digraphs. This can help make digraphs more memorable and meaningful to the kids. Jolly Phonics have actions for each of the letters and digraphs in their programme, as you can see in the video below. You could copy these or make up some of your own.

- Give children opportunities to use and apply their knowledge of the new digraphs you teach them. Get them to practice spelling as well as reading words containing the digraphs.

Using alphabet and digraph cards or magnetic letters that contain digraphs can help with spelling words when you introduce a new digraph.

These are useful because they make the digraphs more visible and young kids can spell words more quickly with them. However, it is important to include some handwriting practice too when children are learning to spell.

- Do daily reviews of digraphs that have been taught in previous sessions. You don’t need to review every digraph they’ve met in every session – just choose 1 or 2 to review each day and spend around 10 minutes working on these. Reviews are more effective if you can make children active participants rather than spectators…

- Use digraph flashcards and ask for the digraph sounds.

- Show them printed words containing digraphs and ask them to read the words.

- Say a word and ask them to segment it by saying the letter sounds and digraph sounds in it. It’s easiest to start doing this with words that have initial consonant digraphs such as ‘sh’ or ‘ch’ at first, but you can gradually introduce words with final consonant digraphs and vowel digraphs. Use mostly common one-syllable words at first such as ship, shop, shed, chin, chop, chips, fish, cash, much, rich, rain, nail, tail, see, feet, peek, coat, soap and toast.

- Review a bigger group of digraphs every couple of weeks or so using a digraph song. There are plenty of these to choose from if you do a search on YouTube. Pick one that suits the digraphs you’ve covered and the children you teach.

- Avoid words with mixtures of digraphs (like mountain or flower) in the early stages. Make sure they can read words with single digraphs fluently first.

- Consider the order of teaching digraphs carefully. See ‘What Order Should I Teach Digraphs?’ later in this article.

- Get children to read decodable books that focus on specific digraphs. This helps to reinforce their learning in a more realistic context. The PhonicsPlay site has produced some free decodable comics. These are quite simple but could still be useful as an extra resource. See our article ‘best books for beginning readers’ for sources of free decodable books.

You can also look out for simple words containing digraphs when you are reading regular books with children and ask them to read the words.

Teaching split digraphs

When to Introduce Split Digraphs

Kids can find split digraphs more difficult to grasp than regular digraphs, so make sure you’ve introduced several examples of regular digraphs first. See ‘What Order Should I Teach Digraphs?’ later in this article for suggestions.

Introduce split digraphs when children can demonstrate they’ve grasped the idea of regular digraphs by successfully reading and spelling words that contain them.

How to Introduce Split Digraphs

There are two alternative ways of introducing split digraphs. One method involves showing children simple words where the vowel sound changes when you add the letter e to the end of the word. The letter e at the end of the word is often referred to as a ‘silent e’ or ‘magic e’ or ‘bossy e’.

For example:

- can cane

- pet Pete

- kit kite

- hop hope

- tub tube

There’s an interactive activity that illustrates this method on the Starfall website’s ‘Learn to Read page.’ Click on the image below to access the activity.

This approach can certainly work, and a lot of children have been successfully taught to read split digraph words this way. However, some educators dislike the term ‘silent e’ because they say all letters are silent – they simply represent sounds either as individual letters or as digraphs and trigraphs.

They also criticise using the term ‘magic e’ because it gives the impression the letter is doing something unusual. However, it’s really just combining with another letter to represent a different sound in the same way other letter combinations do in regular digraphs.

These points may be valid, but we don’t think they’re good enough reasons to avoid a method that works, and we’re not aware of any studies that prove the alternative method is superior.

Nevertheless, there are a couple of potential drawbacks to the magic e method…

Firstly, it can be difficult to find suitable words to use as the initial example for some split digraph words.

For instance, if you want to teach kids how to read the word ‘these’, it’s not ideal to start with ‘thes’ because this isn’t a real word. The same problem arises if you want to teach lots other words this way; for example, ‘game’, ‘hole’, ‘bike’, ‘five’ and ‘rule’. None of the words really mean anything without the e on the end.

Another potential drawback of this method is that it doesn’t always help children make a conceptual link to other types of digraphs. This is especially true if the letter e is just bolted on the end of the word without the connection to the vowel being explicitly taught.

Consequently, we favour the alternative method of highlighting both the middle vowel and the final ‘e’ in the word that we describe below.

However, we know that many teachers use the magic e idea very effectively with their students, and we wouldn’t criticize anyone for doing this.

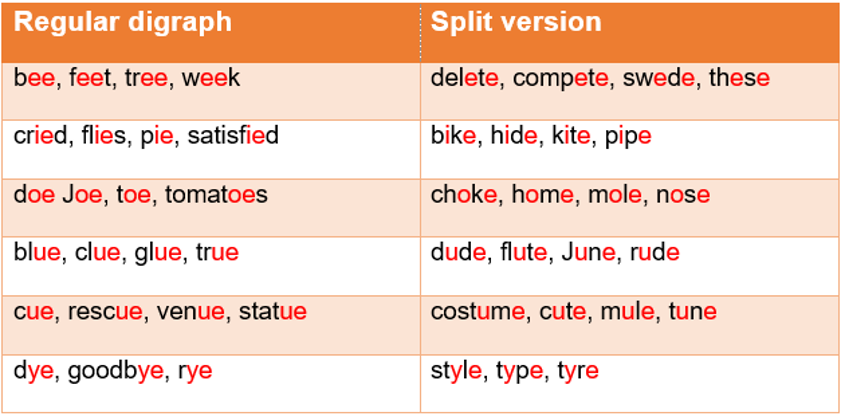

A good way to introduce the alternative method is to first show children some words with regular digraphs that end in e, and then show them the split versions of the same digraphs. It’s more visual and easier for the kids to grasp the idea if you highlight the digraphs in each word.

For example, to introduce the ‘e-e’ split digraph you could first show the children words such as bee, feet, tree and week, and then compare them to another set of words with the split version of the same digraph such as delete, compete, swede and these.

Point out that the digraphs have the same letter pairs and represent the same sound, but one version has another letter before the final e.

When you sound out the split digraph words, point to both the letters in the digraph when you say the vowel sound.

There are some interactive activities that illustrate this method on the Starfall website’s ‘Learn to Read page.’ Click on the links below to access the activities.

|  |  |

|  |

|  |

We’ve listed some example words below that you could use to introduce the various split digraphs…

Note that the ‘ue’ digraph and the split digraph version, ‘u-e’, can represent different sounds in different words in some accents:

- In words such as blue, clue, glue, true, dude, flute, June and rude, it usually represents the /oo/ (ɔɪ) sound.

- In words such as cue, rescue, venue, statue, costume, cute, mule and tune, it represents 2 sounds in some accents – /y/ (j) + /oo/ (ɔɪ).

(The symbols in brackets are the ones used in the International Phonetic Alphabet).

Although there are lots of words that contain the ‘a-e’ split digraph, such as ape, bake, cave, snake and tale, there are far fewer common words that contain the ‘ae’ digraph where it represents the same sound.

Some examples include Gaelic, Israel, reggae and vertebrae. However, if your children aren’t familiar with these words, you could ignore them and just introduce the ‘a-e’ split digraph after you’ve worked through the examples for the other split digraphs.

Once they’ve met 3 or 4 types of split digraphs introduced in the way we suggest above, they should have grasped the idea.

Should You Teach Blends or Digraphs First?

We’re not aware of any studies that prove it’s better to teach digraphs before blends or vice versa, so there’s no definite answer to this question.

However, some successful phonics programs introduce a few simple digraphs first and then teach blends before covering the bulk of the digraphs. We’ve also found this approach to be helpful.

Teaching blends before the more difficult digraphs allows you to illustrate the digraphs with a greater variety of words. This is beneficial because children need to meet plenty of examples to fully grasp a concept.

For instance, all the words below are great examples for learning about digraphs, but they also contain blends. So, it would be better to teach blends first if you want to use examples like these…

Chips, chimp, crunch, splash, brush, swing, bring, green, tree, sleep, toast, groan, float, train, croak, stork, tractor, snort, sport, cloud, flour, ground, count, point, spoil, oink, play, pray, stay, clean, cream, treat, donkey, draw, crawl, straw, prawn, aunt, first, skirt, stir, slurp, burst, enjoy, blew, flew, grew, plane, plate, snake, drive, slide, prize, smile, froze, spoke, stone, smoke, fluke, prune.

What Order Should I Teach Digraphs?

No specific order of teaching digraphs has been proven to be the most effective because with 100+ digraphs in written English there are trillions of potential sequences (permutations) that could be used. It would take many lifetimes to investigate and compare each of the alternatives.

However, it’s reasonable to assume that children should learn digraphs more easily if you teach them in a logical and systematic order.

There are a number of things to consider if you intend to create your own teaching sequence and we discuss some of the important considerations below …

Which Digraphs to Teach First…

In general, it’s more effective to teach simple concepts before introducing more complex ones, so it makes sense to introduce the simplest types of digraphs first.

The most basic digraphs are pairs of adjacent identical consonants and these can be introduced in short one-syllable words such as ‘add’, ‘odd’, ‘off’, ‘huff’, ‘bell’, ‘doll’, ‘hiss’, ‘mess’, ‘buzz’, ‘fizz’ and ‘egg’.

These are a good place to start with digraphs because the letter-pairs represent the same sound as the individual letters do. Children just need to learn they only say the sound once even though there are two letters.

The ‘ck’ digraph could also be introduced at this point because this letter pair also represents the same sound as the individual letters. It can be illustrated using simple words such as duck, muck, peck and neck.

Most of the remaining digraphs are more difficult because they contain a mixture of letters and they represent different sounds from the sounds normally represented by the individual letters.

For example, the ‘al’ digraph, represents the /or/ sound (ɔ:) in words such as ‘talk’ and ‘wall’, which is quite different from the sounds usually represented by the individual letters ‘a’ and ‘l’.

And there’s another layer of difficulty with this digraph because the letter pair represents different sounds in a lot of words. For example, ‘al’ doesn’t correspond to /or/ in any of the following words: ‘Alps’, ‘talc’, ‘halo’, ‘animal’, ‘hospital’, ‘half’ and ‘palm’.

If we use the ‘sh’ digraph as another example, you can see that this also represents a different sound from the individual letters. However, this digraph represents the same /sh/ sound (ʃ) in almost every word it’s found in. This consistency could make ‘sh’ easier for children to learn than the ‘al’ digraph.

Split digraphs (also known as ‘magic e’) which are found in words such as ‘bake’, ‘Pete’ and ‘bone’ can be relatively difficult to learn because the letter pairs aren’t next to each other as in regular digraphs.

And another potential source of confusion is that a variety of common words have letter pairs that appear to be in a split digraph pattern, but the vowels represent different sounds.

For example, the words ‘have’, ‘some’, ‘come’, ‘done’, ‘none’, ‘were’, ‘never’, ‘give’, ‘there’, ‘lived’, ‘river’, ‘seven’, ‘oven’ and ‘camel’ don’t contain the long vowel sounds normally associated with split digraph patterns.

Digraph Frequency

Another consideration when planning a teaching sequence is how often each digraph appears in words. However, this isn’t as straightforward as it might appear.

Should you consider how many times digraphs appear in words taken from a dictionary or how often they occur in words found in an average child’s vocabulary?

And how frequently digraphs occur in children’s books could also be important because some words are repeated more often in texts than others.

For example, the researcher Edward Fry found that 100 high-frequency words make up approximately 50% of the words in an average piece of writing, and around 300 words make up approximately 65 per cent of all written material.

Some digraphs are more common in lists of high-frequency words than they are in wider vocabulary lists. For instance, ‘th’ is the most common digraph in a list of 300 of the highest frequency words1, but it’s only the 9th most common digraph in a vocabulary list of over 17,000 words2.

What Are the Most Common Digraphs?

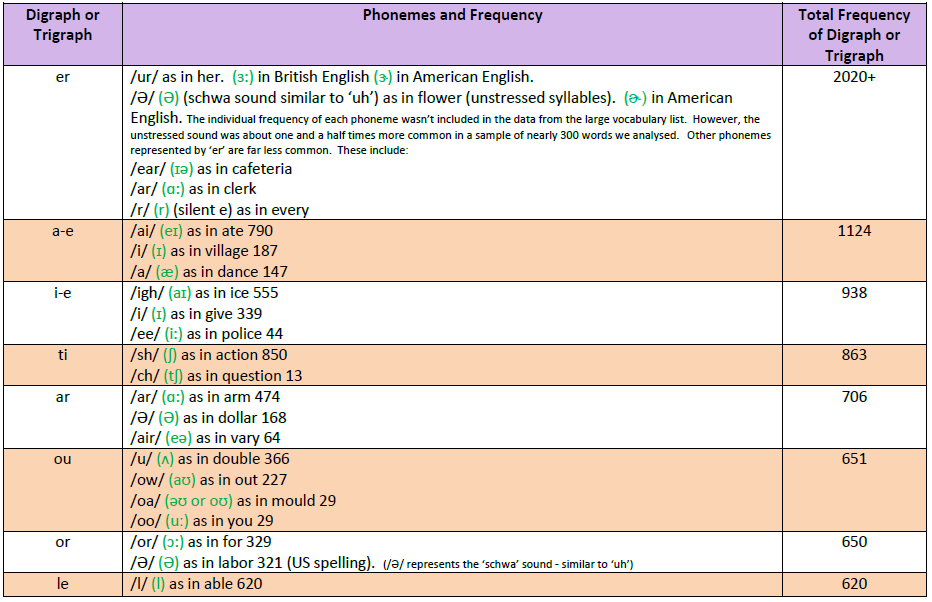

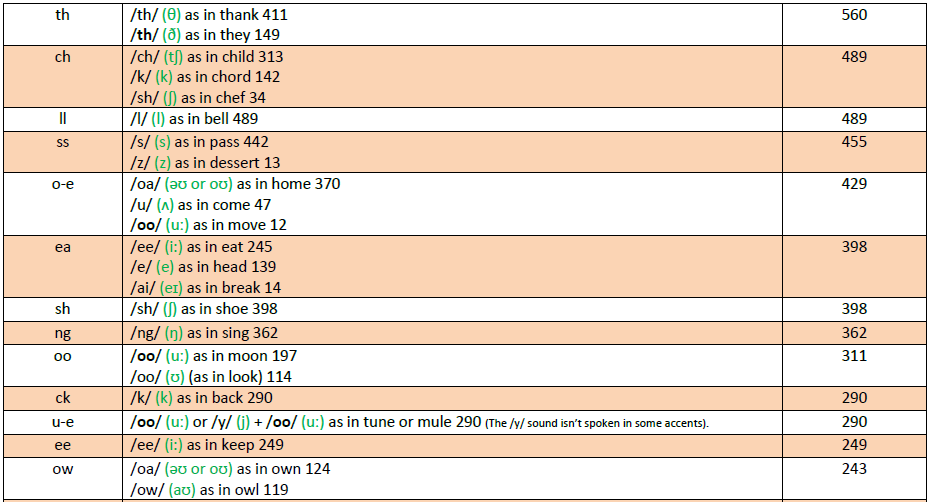

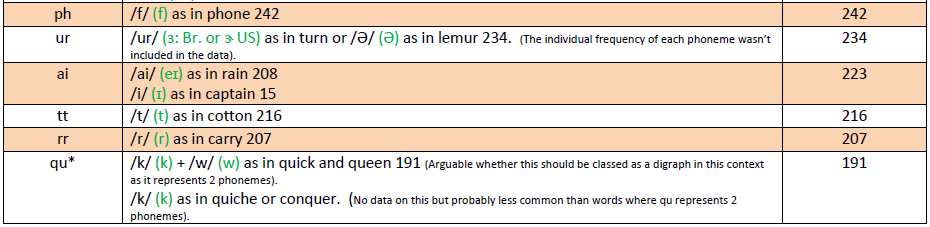

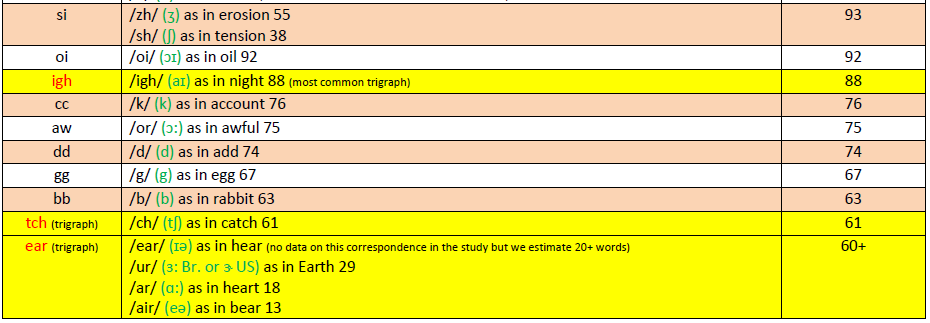

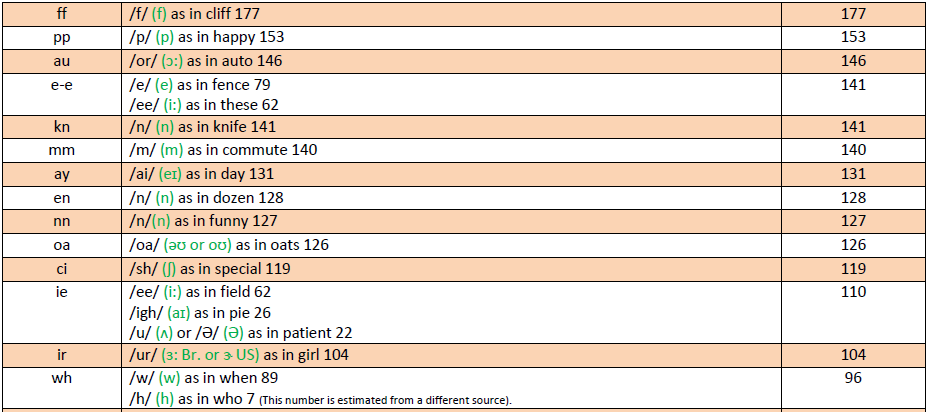

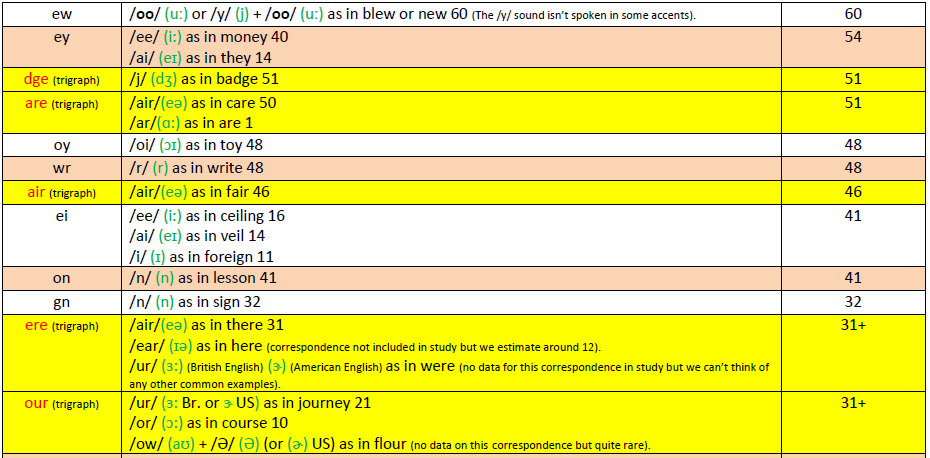

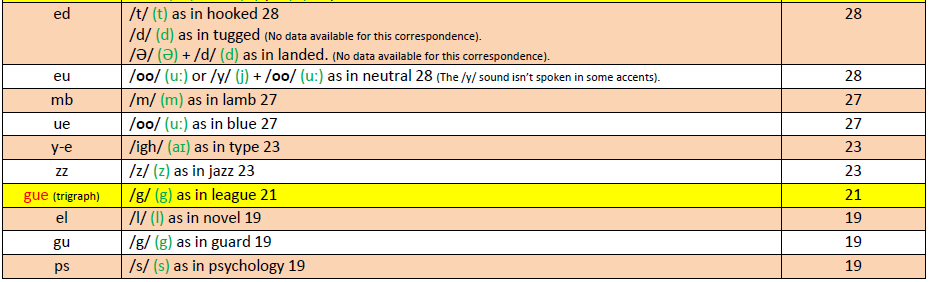

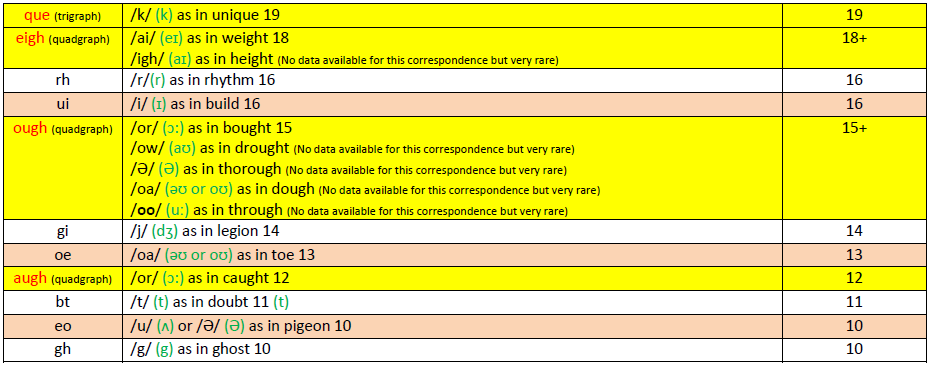

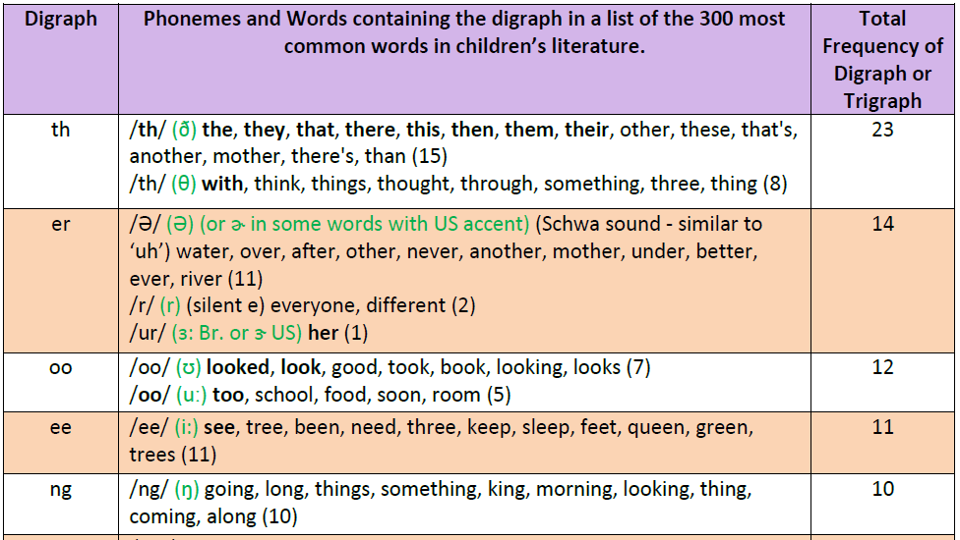

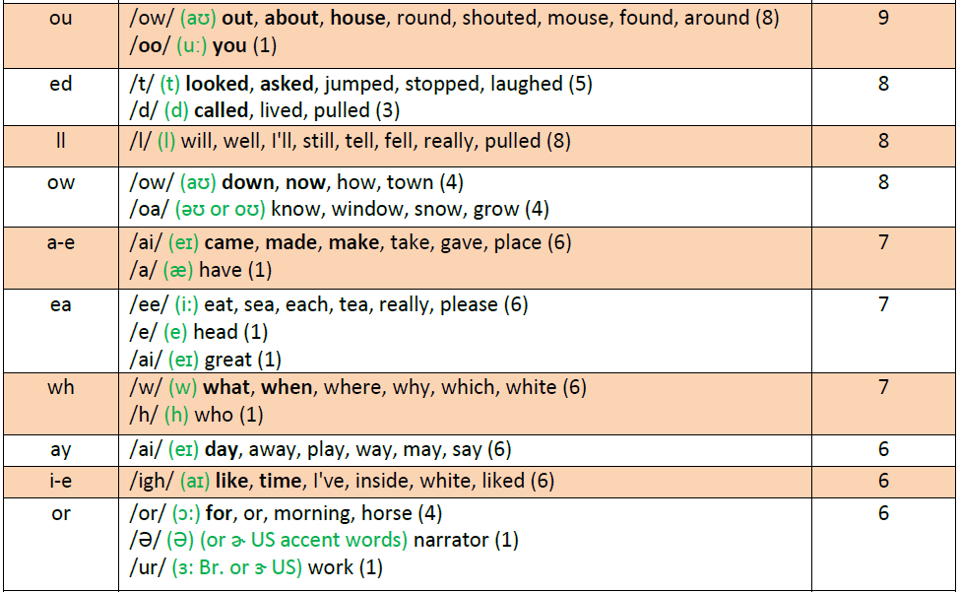

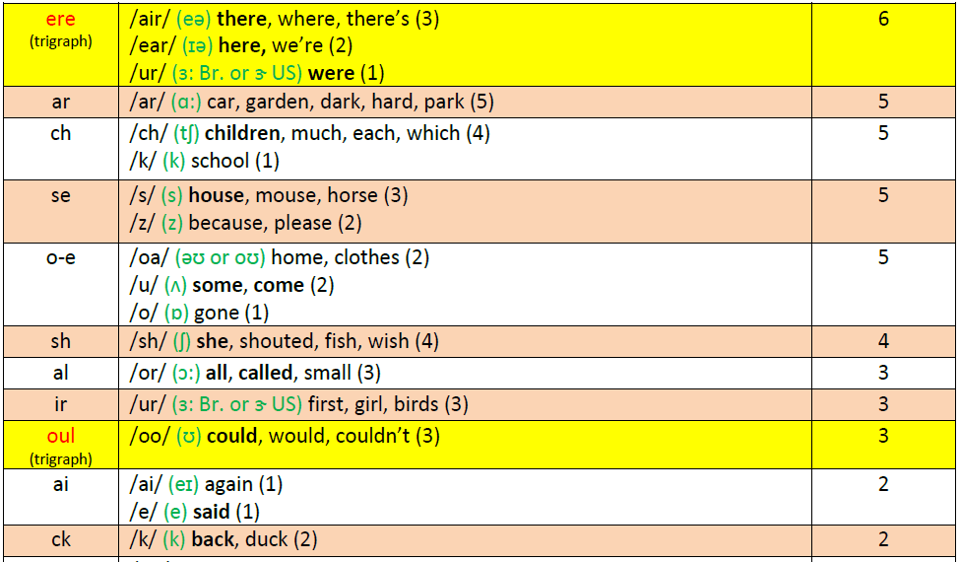

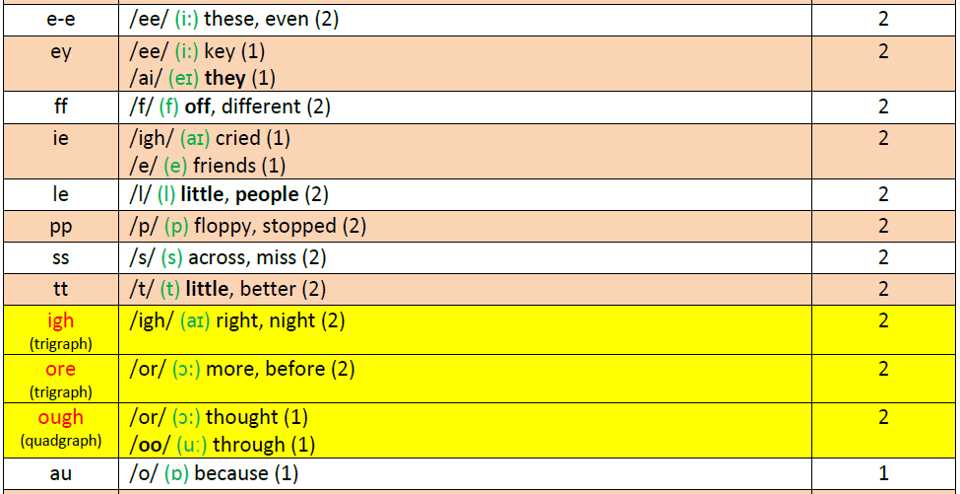

We’ve compiled 2 separate lists below. One is based on data from a 17,310-word vocabulary list2 and the other is compiled from a list of the top 300 high-frequency words in children’s literature1.

The letters between forward slashes / / are used to represent phonemes in the UK Government’s Letters and Sounds phonics programme1. The green symbols in round brackets are used in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Frequency of Digraphs and Trigraphs in Words from a Large Vocabulary List

Although the source of the data included in this list is very comprehensive, it should not be viewed as a definitive list. Words in vocabularies can change over time and different academics classify some digraphs in alternative ways. Nevertheless, it should provide a reasonable guide to the relative frequency of most digraphs.

Click on the following link to download this table as a pdf document.

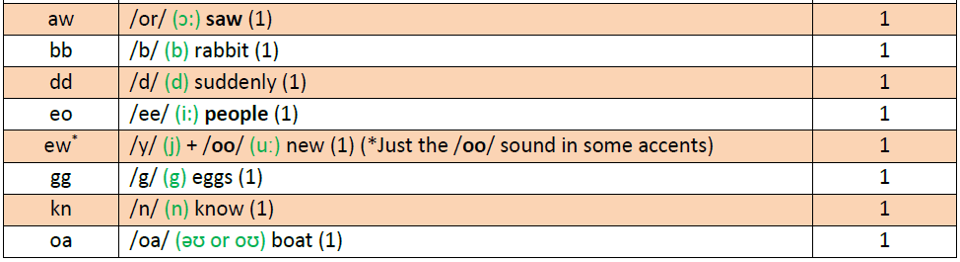

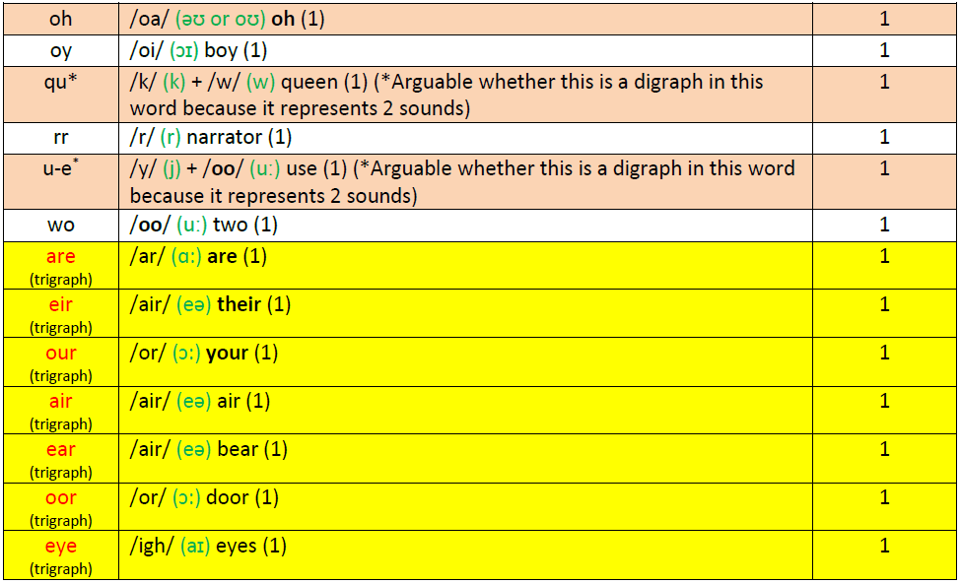

Frequency of Digraphs and Trigraphs in a List of High Frequency Words

The data in the table below are compiled from a list of the 300 most common words in children’s literature published in the UK Government’s Letters and Sounds Phonics guidance booklet. Words in bold are in the top 100 common words.

The exact order of words in high-frequency lists can vary with different sources, but the majority of words in the alternative lists are the same.

The letters between forward slashes / / are used in the UK Government’s Letters and Sounds phonics programme. The green symbols in round brackets are used in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Click on the following link to download this table as a pdf document.

Something to consider if you are planning a teaching sequence for digraphs is that some of the more common digraphs are relatively difficult. For instance, the sound /sh/ (ʃ) is represented much more often by the ‘ti’ digraph in words than it is by the ‘sh’ digraph.

‘ti’ represents /sh/ in words such as action, initial, station and mention. However, many of the words containing ‘ti’ as a digraph are fairly difficult multi-syllable words.

Also, there are many more common words where ‘ti’ doesn’t represent /sh/; for example, tie, tin, tip, tiny, tidy, stir, stink, stiff, stick, active, artic, antics, notice, tactic and biting.

In contrast, ‘sh’ represents the /sh/ sound in a variety of simple words that beginning readers are likely to meet – fish, dish, wish, cash, bash, mash, ship, shop, shed, shrimp, shrink etc. And, as we said earlier, it rarely (if ever) represents another sound. Consequently, it might be preferable to teach ‘sh’ before ‘ti’, even though it’s less common.

Common Sounds

An alternative strategy is to teach digraphs in groups based on the sounds they represent. This is approach is often used in linguistics phonics programmes.

With this method, most of the digraphs that represent a particular sound are taught together along with any other letter combinations that represent the same sound.

So, for example, digraphs taught for the /ai/ sound might include ‘ai’ as in rain, ‘ay’ as in play, ‘a-e’ as in snake and ‘ey’ as in obey. The ‘eigh’ quadgraph found in words such as eight might also be taught at this time.

This has some advantages because it groups digraphs together in a meaningful way, but it could result in some relatively rare digraphs being taught before more common ones.

One final consideration is that you might not need to teach some of the digraphs at all.

Most reading programmes only include a fraction of the 100+ digraphs in written English. For example, the UK government’s Letters and Sounds programme only mentions around 55 digraphs and provides example words for less than 50 of these. The popular Jolly Phonics programme contains less than 40 digraphs.

It seems it isn’t necessary to formally teach every digraph that exists. Once kids have been taught a reasonable number of digraphs, they get the idea and can decipher other digraph patterns for themselves, although they might do this subconsciously.

Of course, if you notice that a child continues to stumble over a particular letter pattern, it would be advisable to teach this more explicitly and provide them with plenty of examples to practise.

And it’s still a good idea to practice spelling a variety of words containing digraphs because kids often find spelling more difficult than reading.

A Suggested Teaching Sequence for Digraphs and Trigraphs.

We’ve provided a suggested order for teaching digraphs in the table below.

We don’t claim that our sequence is superior to all other alternatives, but we have made every effort to come up with a logical and systematic order by taking into account the relative complexity and frequency of each digraph as we discussed above.

However, there are many ways these factors can be interpreted and we’re sure good arguments could be made to introduce some digraphs earlier or later in the sequence. So, use our suggestions as a guideline rather than a set of rigid instructions and be flexible in your approach.

We’ve also included the teaching sequences for digraphs and trigraphs in some popular phonics programmes to give you examples of alternative approaches.

1 | dd, ff, gg, ll, ss, zz (see note 1 below). | 17 | wh, kn, wr, gn, gu, gh, rh (see note 9 below). |

2 | ck (see note 2 below). | 18 | ay, ai |

3 | qu (see note 3 below). | 19 | ur, ir |

4 | th (see note 4 below). | 20 | ph |

5 | er (see note 5 below). | 21 | igh |

6 | ar | 22 | ey |

7 | ou | 23 | au, aw |

8 | or | 24 | oa |

9 | ch and tch (see note 6 below) | 25 | ew, eu |

10 | ea | 26 | oi, oy |

11 | ee and e-e, ie and i-e, oe and o-e, ue and u-e, a-e, ye and y-e (see note 7 below) | 27 | ear, are, air, ere |

12 | sh | 28 | dge |

13 | ng | 29 | ci and ti (see note 10 below) |

14 | oo | 30 | si |

15 | ow | 31 | ei |

16 | le, ed, se, mb, bt (see note 8 below) | 32 | Other less common digraph, trigraph and quadgraph spellings such as our, eigh, ough, augh, gue (league) and que (unique). Include unusual spellings found in common exception words such as ‘eo’ (people), ‘oul’ (could), ‘ore’ (more) and ‘wo’(two). |

- Double consonants are relatively simple to learn because they represent the same sounds as their individual letters. They can also be used to construct simple one-syllable words very early in a phonics programme. For example, ‘add’, ‘odd’, ‘off’, ‘huff’, ‘egg’, ‘bell’, ‘doll’, ‘hiss’, ‘mess’, ‘buzz’, and ‘fizz’. Other double consonant digraphs that don’t often appear in one-syllable words, such as ‘bb’, ‘pp’, ‘rr’ and ‘tt’, can be introduced when children start learning to read 2-syllable words.

- The ‘ck’ digraph follows a similar pattern to the double consonants because the letter pair represents the same sound as the individual letters. It can be illustrated using simple one-syllable words such as duck, muck, peck and neck.

- Technically, ‘qu’ isn’t a digraph in most words as it usually represents 2 sounds (/k/ + /w/). However, since the letter q is almost always paired up with u in words, it makes sense to teach it as a letter pair when children are first learning the sounds represented by individual letters of the alphabet.

- ‘th’ is the most common digraph in lists of high frequency words. It was in the top 10 digraphs found in a vocabulary list of over 17,000 words and it’s found in the most common word of all – ‘the’.

- ‘er’ was the most common digraph in a vocabulary list of over 17,000 words and it’s the second most common in a list of high frequency words.

- The ‘tch’ trigraph represents the same sound and has a very similar spelling to ‘ch’, so it makes sense to teach these letter patterns alongside each other, even though ‘tch’ is less common in words. It can be introduced using simple one-syllable words such as catch, match, fetch, stretch, hutch, pitch and switch.

- Some split digraphs are very common in words and it can help children to recognise them and make a connection if they are taught alongside their non-split versions. See our section on Teaching split digraphs.

- Some of these word endings are very common and they all contain silent letters*, so it can be convenient to group them together.

*Technically, all letters are silent – they simply represent sounds. However, the phrase can be a convenient way of describing similar digraphs sometimes. - These digraphs are used at the beginning of some fairly common words and they share a similar feature to the word endings described above.

- Both of these digraphs can represent the /sh/ (ʃ) However, we’ve put them later in the sequence because they don’t represent this sound as consistently as the ‘sh’ digraph and they tend to act as digraphs in multi-syllable words which beginning readers can find more difficult to read.

Teaching Sequences for Digraphs and Trigraphs in Some Popular Phonics Programmes

Digraphs and Trigraphs in Letters and Sounds

Letters and Sounds1 is the name of the UK Government’s phonics guidance booklet which was published in 2007. The booklet outlines a programme for teaching phonics that is split into 6 phases and many English schools still broadly follow these guidelines.

Amy from Little Learners explains the phases in the short video below…

See below for an overview of the age ranges and timings of each phase.

Digraphs in Phase 1

No letters or digraphs are introduced in Phase 1 of the Letters and Sounds programme. The focus is on developing children’s speaking and listening skills and their phonological awareness.

Digraphs in Phase 2

| Digraph | Digraph Word List |

| ck | kick, sock, sack, dock, pick, sick, pack, ticket, pocket. |

| ff | off, puff, huff, cuff. |

| ll | bell, fill, doll, tell, sell, Bill, Nell, dull. |

| ss | ass, less, hiss, mass, mess, boss, fuss, hiss, pass, kiss, Tess, fusspot. |

Digraphs in Phase 3

| Digraph/ Trigraph | Digraph or Trigraph Word List |

| zz | buzz, jazz. |

| qu* | quiz, quit, quick, quack, liquid. |

| ch | chop, chin, chug, check, such, chip, chill, much, rich, chicken. |

| sh | ship, shop, shed, shell, fish, shock, cash, bash, hush, rush. |

| th | them, then, that, this, with, moth, thin, thick, path, bath. |

| ng | ring, rang, hang, song, wing, rung, king, long, sing, ping-pong. |

| ai | wait, Gail, hail, pain, aim, sail, main, tail, rain, bait. |

| ee | see, feel, weep, feet, jeep, seem, meet, week, deep, keep. |

| igh | high, sigh, light, might, night, right, sight, fight, tight, tonight. |

| oa | coat, load, goat, loaf, road, soap, oak, toad, foal, boatman. |

| oo | too, zoo, boot, hoof, zoom, cool, food, root, moon, rooftop. Look, foot, cook, good, book, took, wood, wool, hook, hood. |

| ar | bar, car, bark, card, cart, hard, jar, park, market, farmyard. |

| or | for, fork, cord, cork, sort, born, worn, fort, torn, cornet. |

| ur | fur, burn, urn, burp, curl, hurt, surf, turn, turnip, cards. |

| ow | now, down, owl, cow, how, bow, pow, row, town, towel. |

| oi | oil, boil, coin, coil, join, soil, toil, quoit, poison, tinfoil. |

| air | air, fair, hair, lair, pair, cairn. |

| ure | sure, lure, assure, insure, pure, cure, secure, manure, mature. |

| er | hammer, letter, rocker, ladder, supper, dinner, boxer, better, summer, banner. |

Note that some digraphs can represent more than one sound (sometimes depending on accents). Words in different colours indicate alternative sounds.

* It’s arguable whether ‘qu’ is acting as a digraph in these words because it represents 2 sounds – /k/ and /w/.

Digraphs and Trigraphs in Phase 4

No new digraphs or trigraphs are introduced in phase 4 of letters and sounds. The focus is on reading and spelling words containing adjacent consonants (blends) and words with more than one syllable.

Digraphs and Trigraphs in Phase 5

(A few quadgraphs (tetragraphs) are also included in this phase).

Note that some digraphs can represent more than one sound (sometimes depending on accents). Words in different colours in the table below indicate alternative sounds.

* These example words are not listed in the Letters and Sounds document.

Alternative sounds for digraphs introduced in phase 3…

| Digraph/ Trigraph | Example Words |

| ow | low, grow, snow, glow, bowl, tow, show, slow, window, rowing-boat. |

| er | her, fern, stern, Gerda, herbs, jerky, perky, Bernard, servant, permanent. |

| ch | school, Christmas, chemist, chord, chorus, Chris, chronic, chemical, headache, technical. Chef, Charlene, Chandry, Charlotte, machine, brochure, chalet. |

| ear | pear, bear, wear, tear, swear. Learn, earn, earth, pearl, early, search, heard, earnest, rehearsal. |

| or | word, work, world, worm, worth, worse, worship, worthy, worst. |

Digraphs in Phase 6

Children explore prefixes and suffixes in phase 6 but most of these are not digraphs or trigraphs. The suffix ‘ed’ can act as a digraph in some words. For example:

alarmed, baffled, behaved, camouflaged

chopped, hopped, jumped, walked

Digraphs and Trigraphs in Jolly Phonics

Jolly Phonics is an established and popular phonics programme that’s been shown to be effective in various academic studies.

Digraphs and trigraphs are usually introduced in the following sequence:

| Week of Programme | Digraphs and Trigraphs Introduced |

| 2 | ck, (words with digraphs made from pairs of identical consonants such as ‘hill’, ‘egg’, ‘huff’ and ‘miss’ may also introduced alongside the ‘ck’ digraph). |

| 4 | ai |

| 5 | oa, ie, ee, or |

| 6 | ng, oo (as in ‘foot’), oo (as in ‘boot’) |

| 7 | ch, sh, th (as in thin), th (as in this), qu, ou |

| 8 | oi, ue, er, ar |

| 9 onwards | Alternative digraph and trigraph spellings for vowels. |

Alternative digraph and trigraph spellings for vowels…

Long a: ay, a-e

Long e: ea

Long i: igh, i-e

Long o: ow, o-e

Long u: ew (as in few), u-e (as in duke)

Long oo: ew (as in blew), u-e (as in June)

‘er’ sound: it, ur

‘or’ sound: au, aw, al

‘oi’ sound: oy

‘ou’ sound: ow

See our tables of consonant digraphs and vowel digraphs for example words for each of the digraphs above.

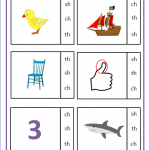

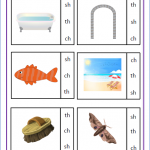

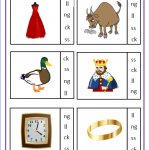

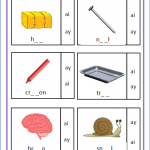

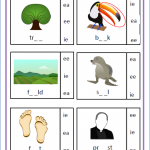

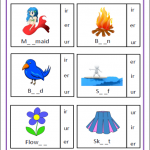

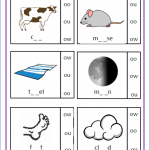

Free Digraph Worksheets

We’ve produced a variety of free digraph activities to help improve children’s segmenting/spelling skills. Click on the images below to access these resources.

Your children might also enjoy playing digraph bingo as demonstrated by Mr Thorne in the video below…

References

- Letters and Sounds: Principles and Practice of High Quality Phonics: Notes of Guidance for Practitioners and Teachers, Primary National Strategy. Department for Educatio and Skills, 2007.

- Fry, E. (2004) Phonics: A Large Phoneme-Grapheme Frequency Count Revised, Journal of Literacy Research, V. 36 No.1 2004 PP.85-98